- Главная

- Разное

- Дизайн

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Аналитика

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Красота и здоровье

- Финансы

- Государство

- Путешествия

- Спорт

- Недвижимость

- Армия

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

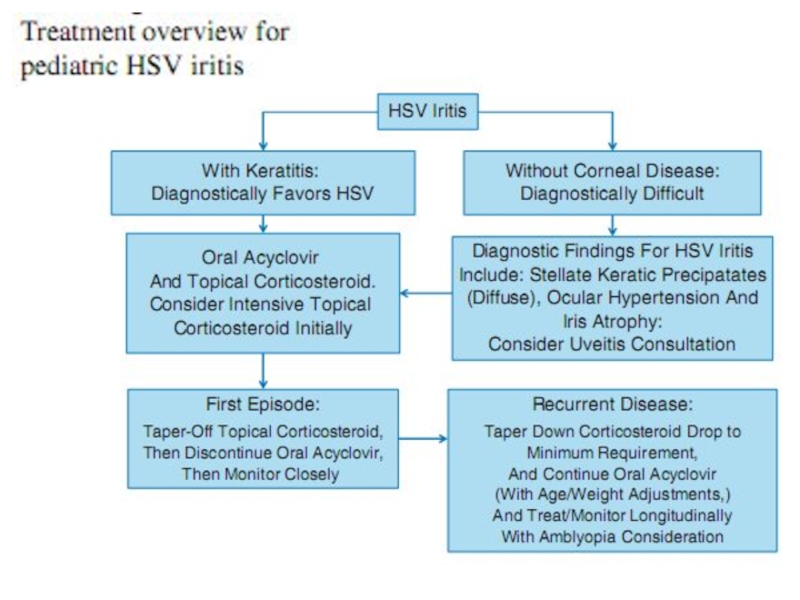

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Pediatric HSV Epithelial Keratitis презентация

Содержание

- 1. Pediatric HSV Epithelial Keratitis

- 3. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis is an

- 4. HSV keratitis occurs when the infection reaches

- 5. Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infection and inflammation eventually

- 6. HSV keratitis in children may differ from

- 8. HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS PRIMARY HSV

- 10. RECURRENT HSV INFECTIONS Multiple factors are thought

- 11. Sunlight, local physical trauma, hormonal changes, and

- 12. Epithelial ulcers may cause sensitivity to

- 18. Fig. 1.17 (c) Afer a blink, the

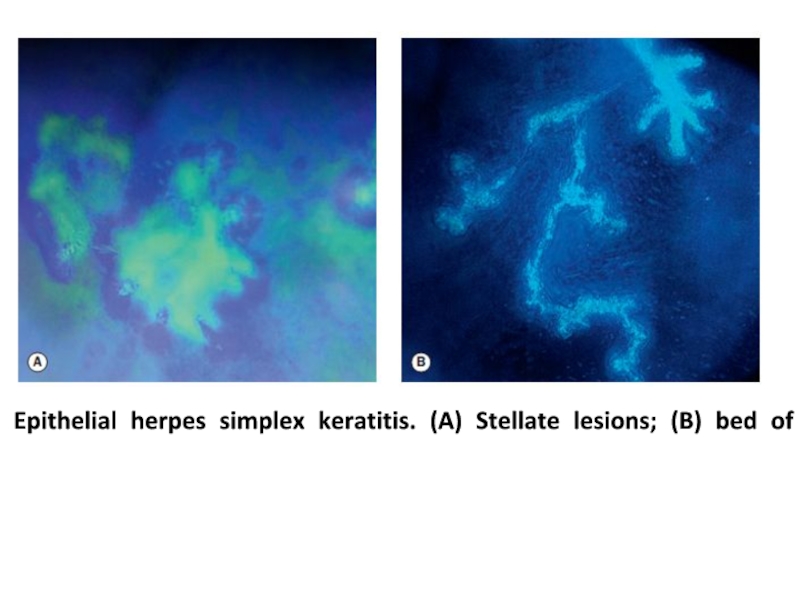

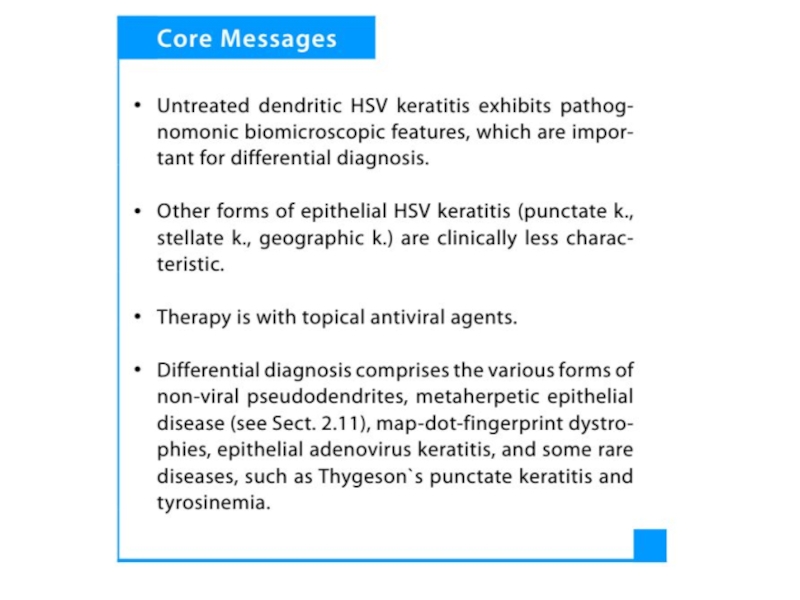

- 20. Epithelial herpes simplex keratitis. (A) Stellate lesions; (B) bed of a dendritic ulcer stained with fuorescein;

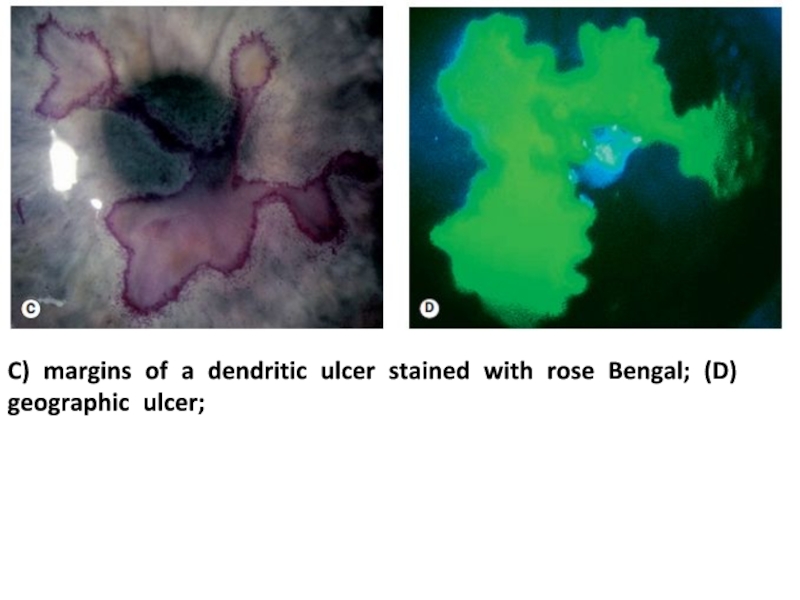

- 21. C) margins of a dendritic ulcer stained with rose Bengal; (D) geographic ulcer;

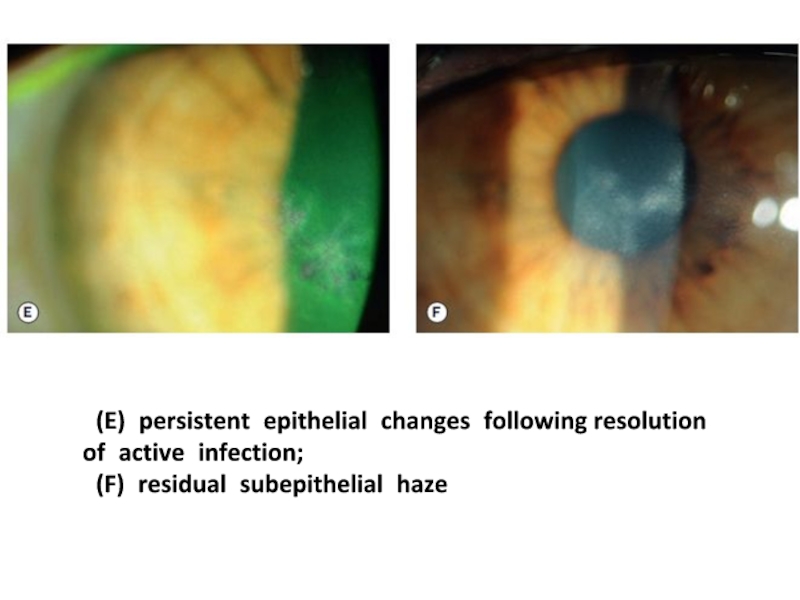

- 22. (E) persistent epithelial changes following resolution of active infection; (F) residual subepithelial haze

- 28. In particular, HSV culture and

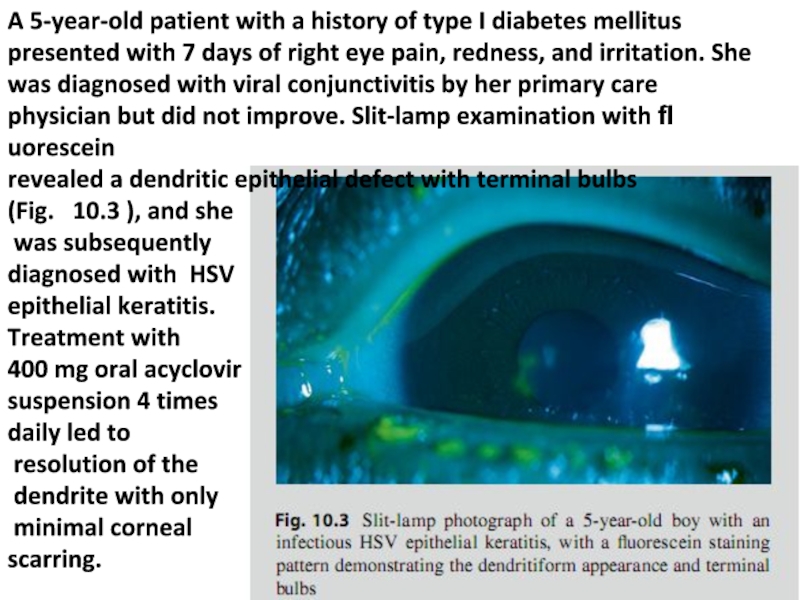

- 29. A 5-year-old patient with a history of

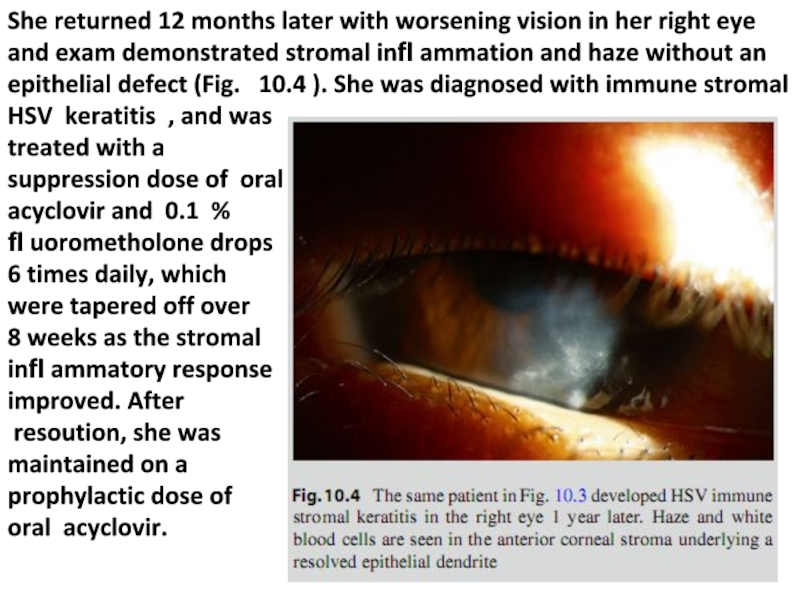

- 30. She returned 12 months later with worsening

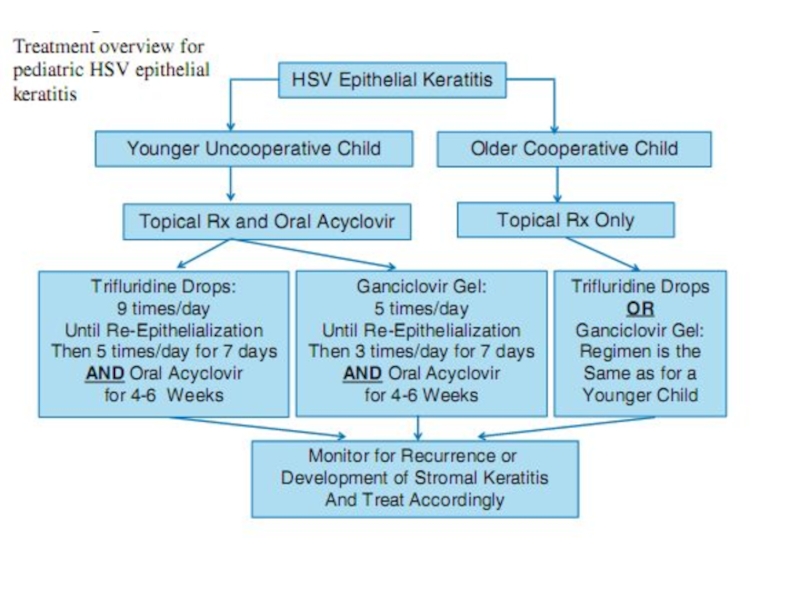

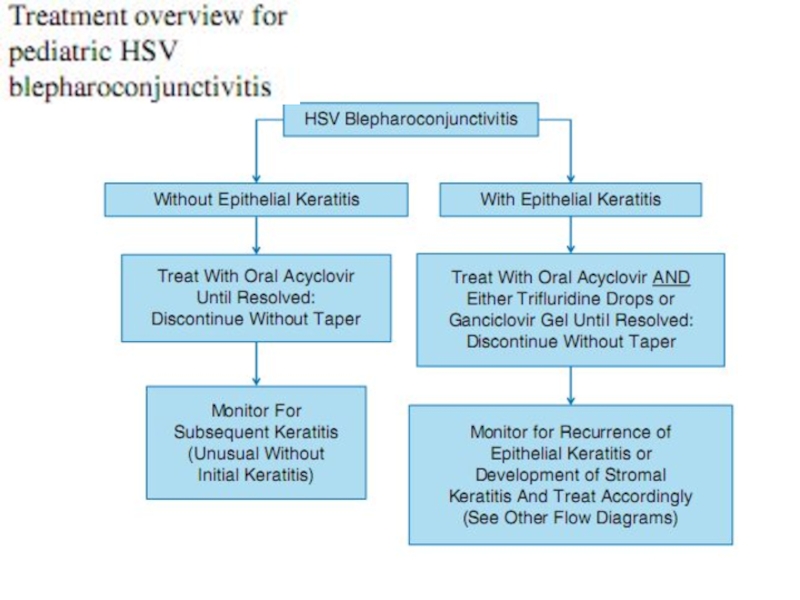

- 31. Although HSV epithelial disease may resolve

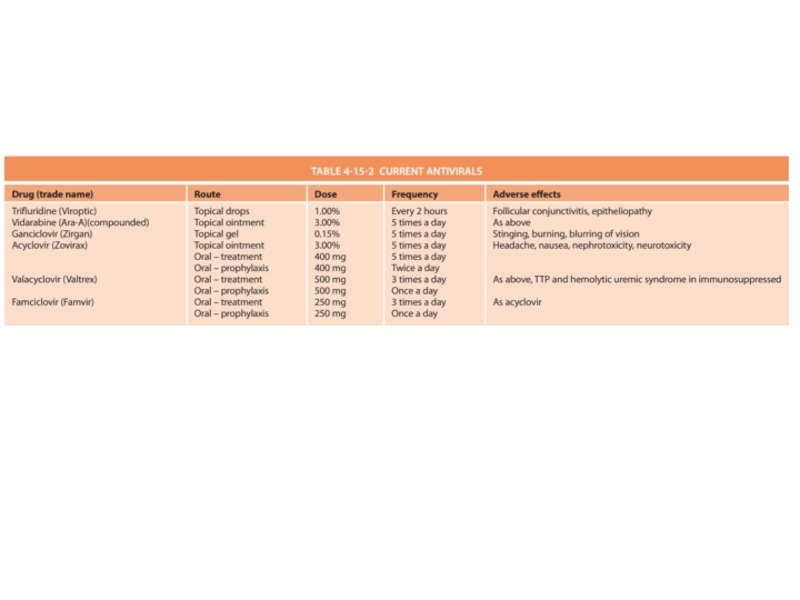

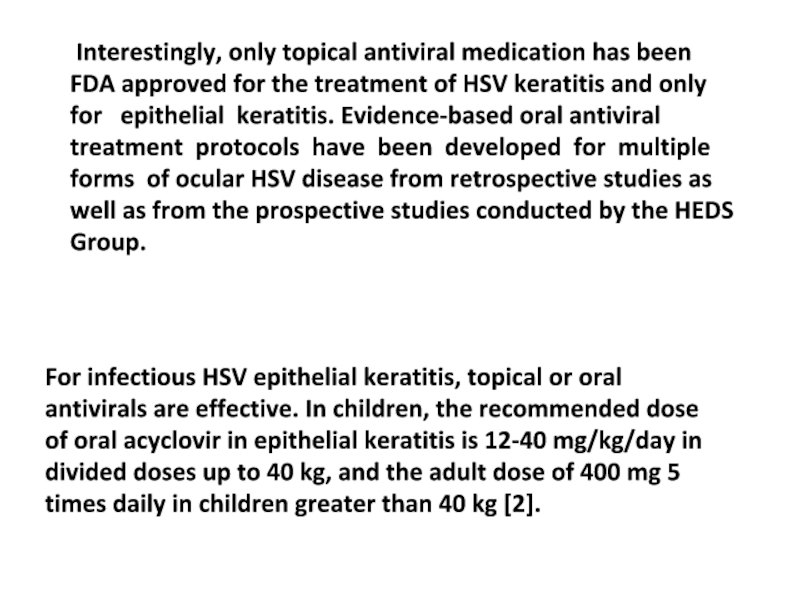

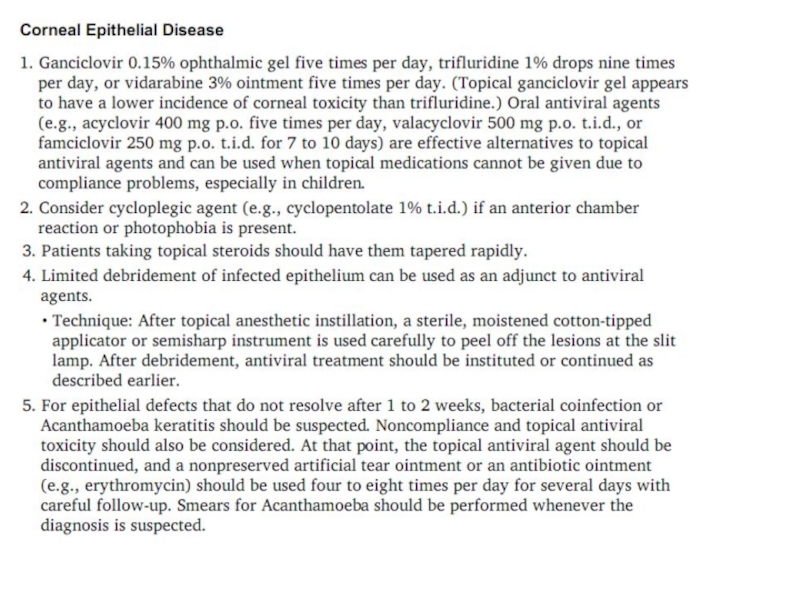

- 33. For infectious HSV epithelial keratitis, topical or

- 35. Oral acyclovir did not hasten healing

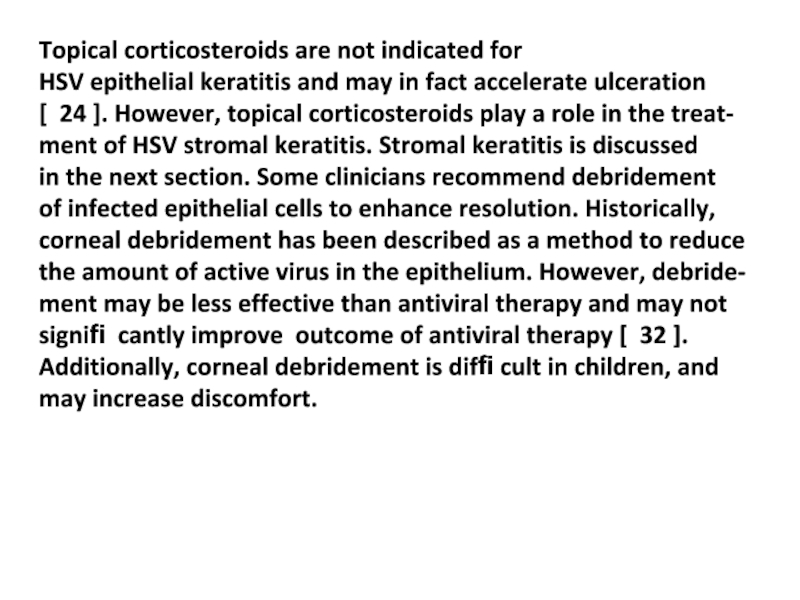

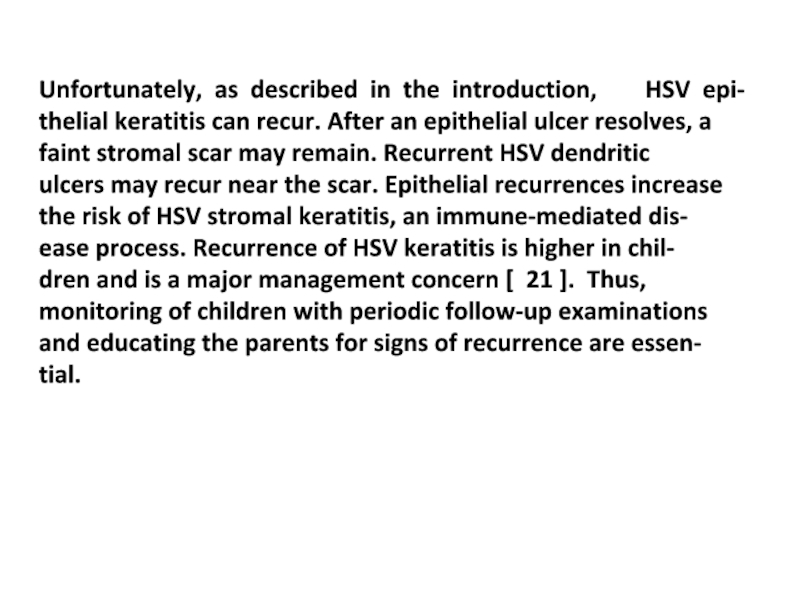

- 36. Topical corticosteroids are not indicated for

- 37. Unfortunately, as described in the introduction,

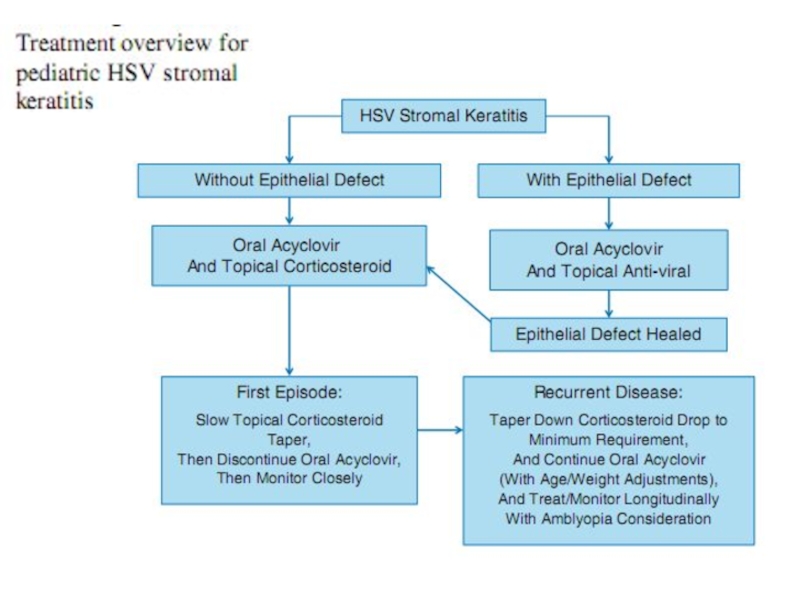

- 41. HSV stromal keratitis classically involves an

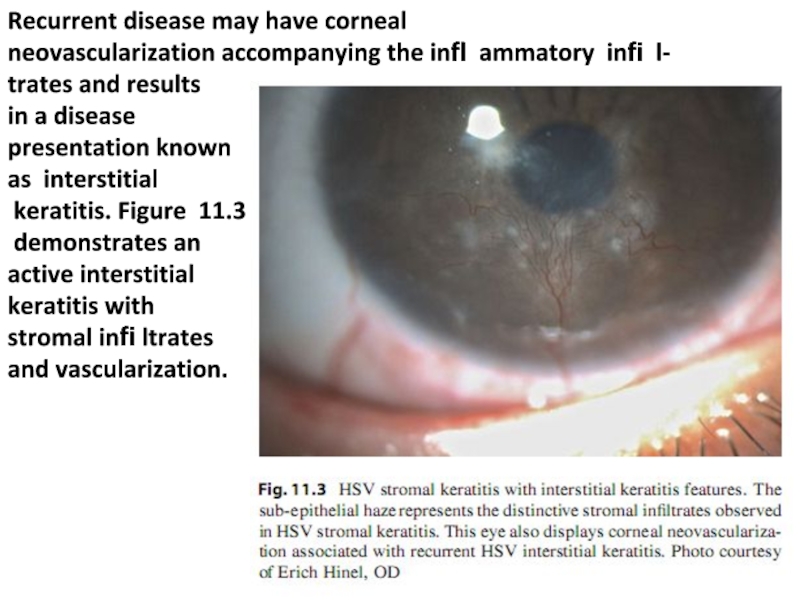

- 42. Recurrent disease may have corneal neovascularization

- 43. Treatment of stromal keratitis in children

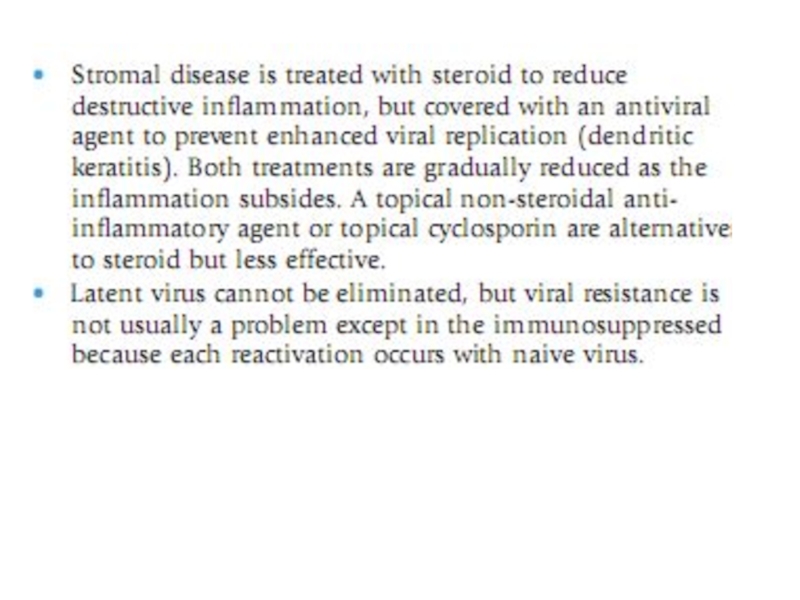

- 44. The topical corticosteroid may be tapered and

- 45. Valacyclovir may be considered for older

- 46. Epithelial keratitis later followed by stromal keratitis

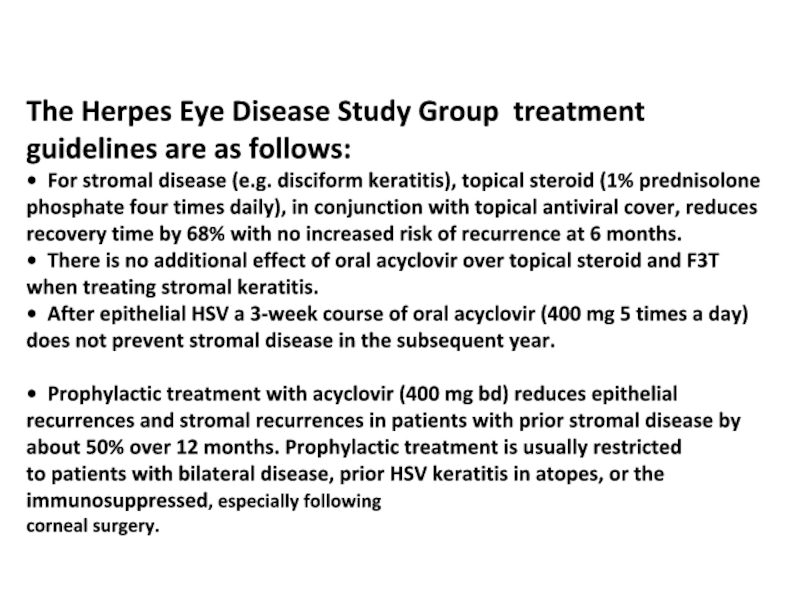

- 49. The Herpes Eye Disease Study Group treatment

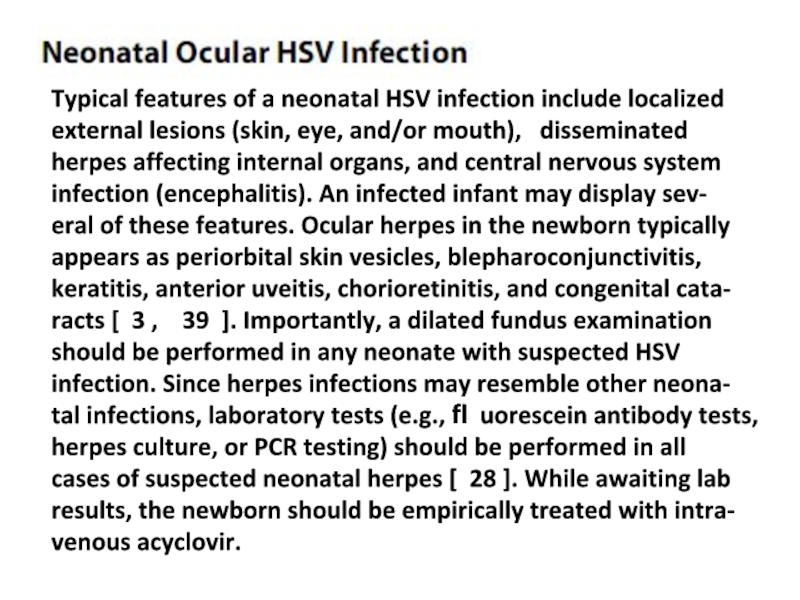

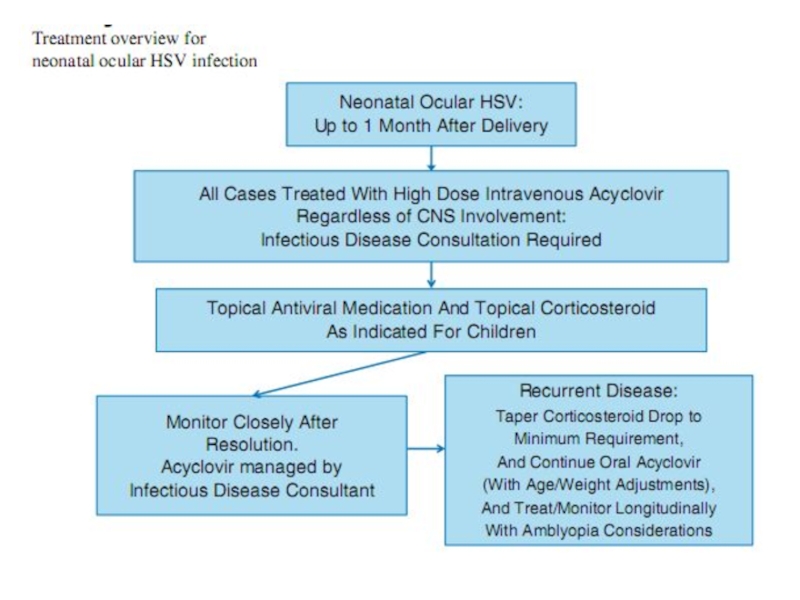

- 51. Typical features of a neonatal HSV infection

- 52. Overall prognosis of neonatal ocular HSV

Слайд 3Herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis is an important cause of ocular

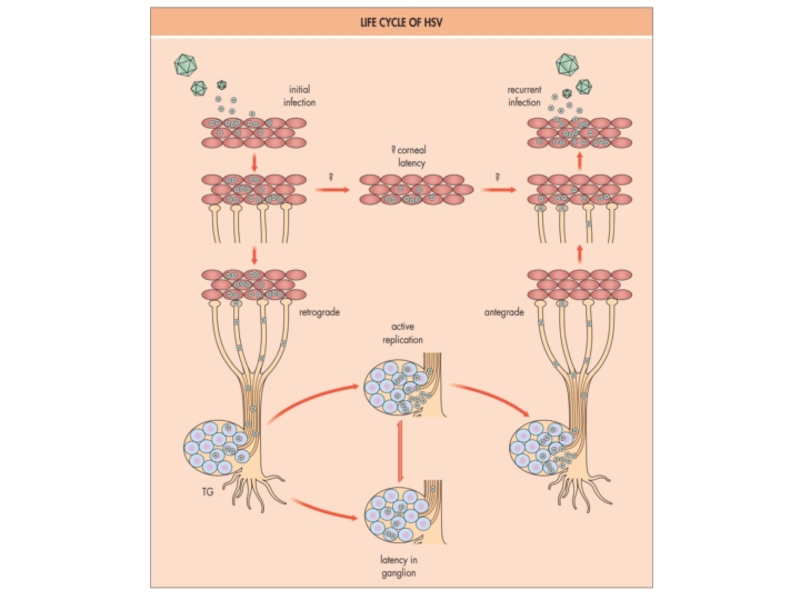

Слайд 4HSV keratitis occurs when the infection reaches the corneal epithelium and

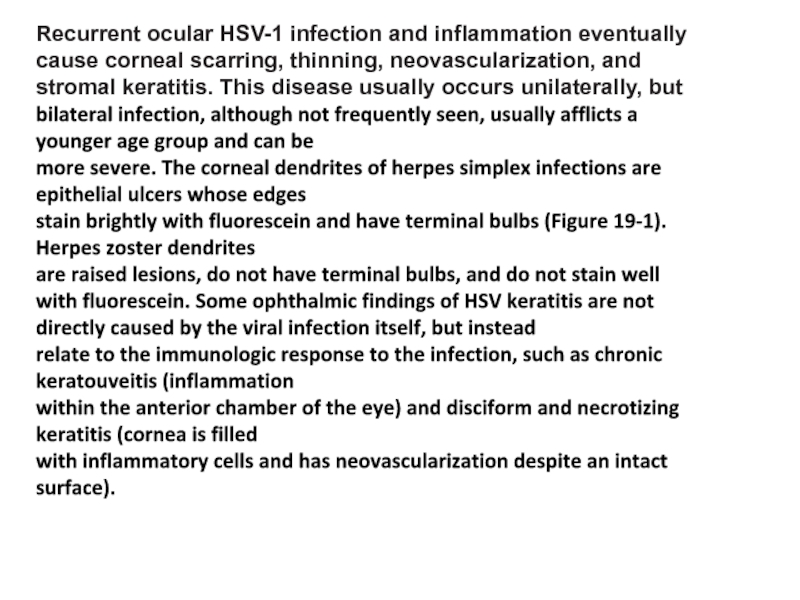

Слайд 5Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infection and inflammation eventually cause corneal scarring, thinning,

Слайд 6HSV keratitis in children may differ from that in adults. The

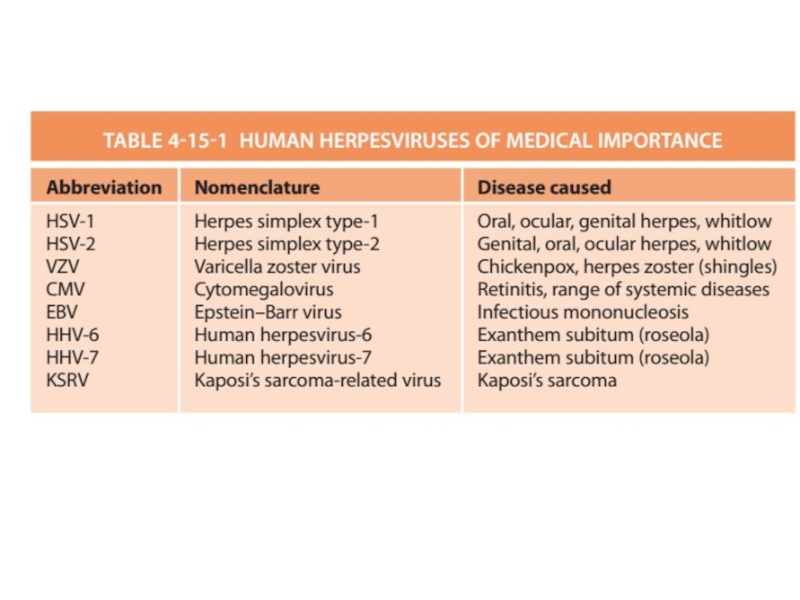

Слайд 8HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS

PRIMARY HSV INFECTION

Primary HSV ocular infection most commonly

Слайд 10RECURRENT HSV INFECTIONS Multiple factors are thought to trigger recurrence, including fever,

Слайд 11Sunlight, local physical trauma, hormonal changes, and

immunological stress (as by

to risk of recurrence of non-ocular herpetic disease [ 9 ].

However, with correction for recall bias, the Herpetic Eye

Disease Study (HEDS) Group found that none of these fac-

tors were a signifi cant cause of recurrent ocular herpes [ 10 ].

However, a history of atopic disease has been associated

with recurrent herpetic eye disease, possibly secondary to

immunologic dysfunction [ 11 – 13 ]. Therefore, the practitio-

ner should inquire about personal and family history of con-

ditions such as asthma, eczema, and seasonal allergies.

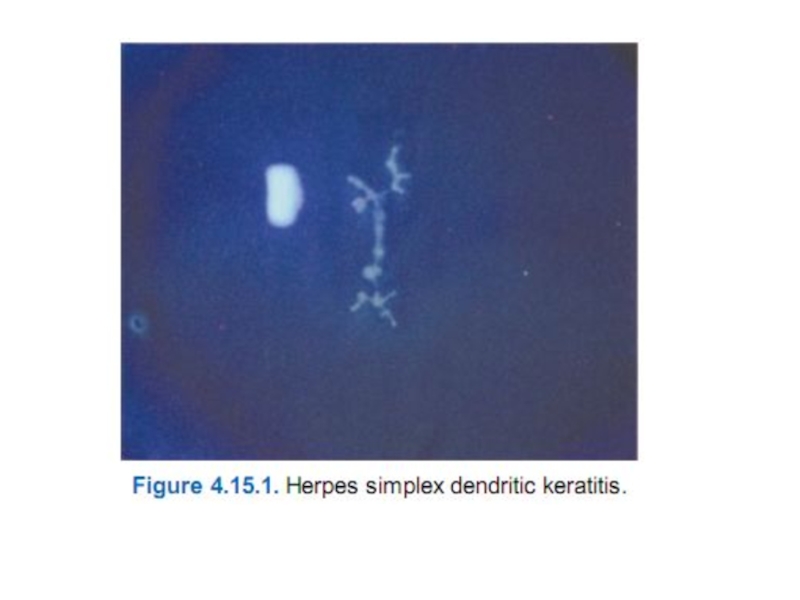

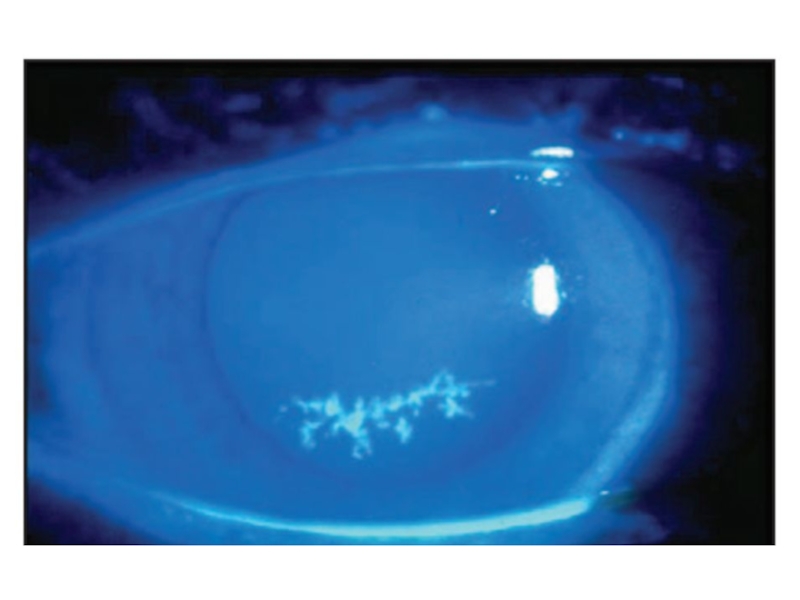

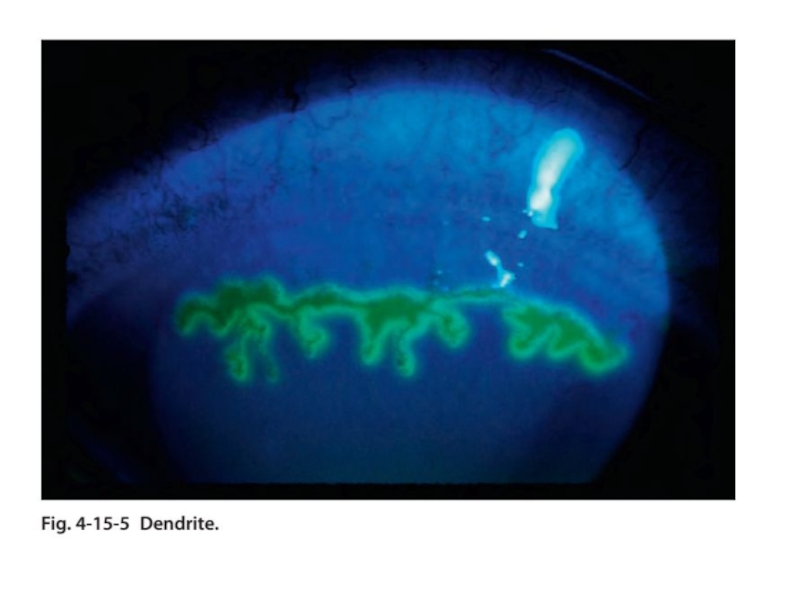

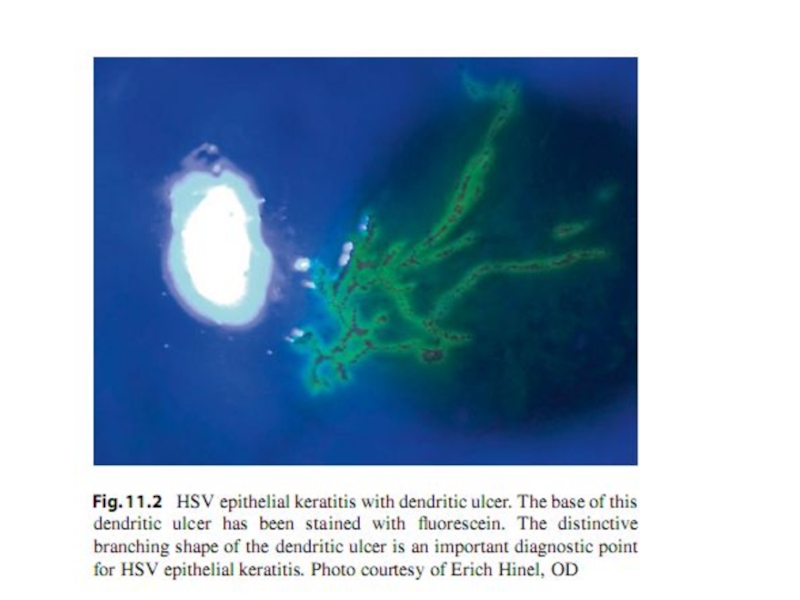

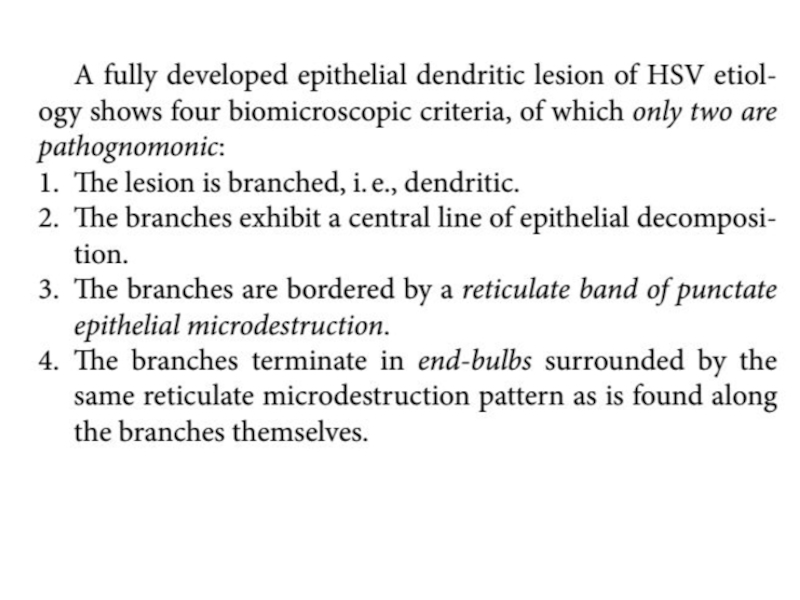

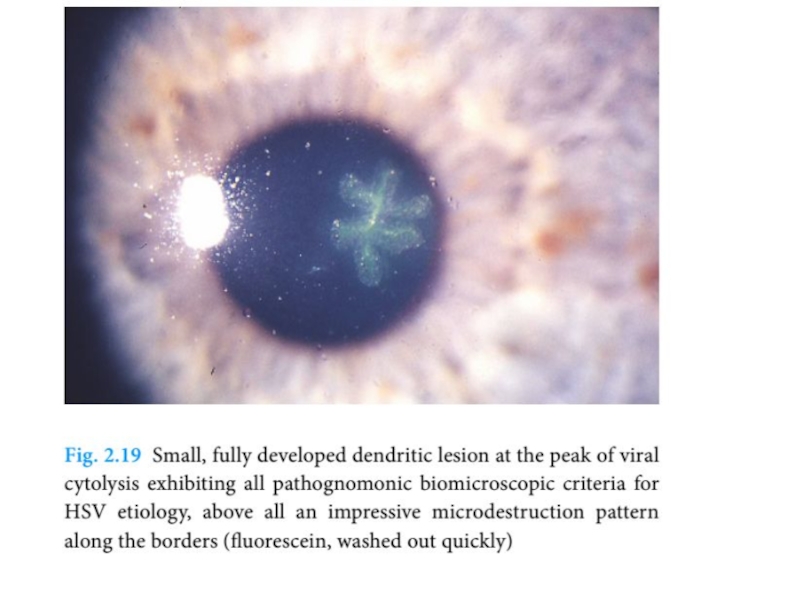

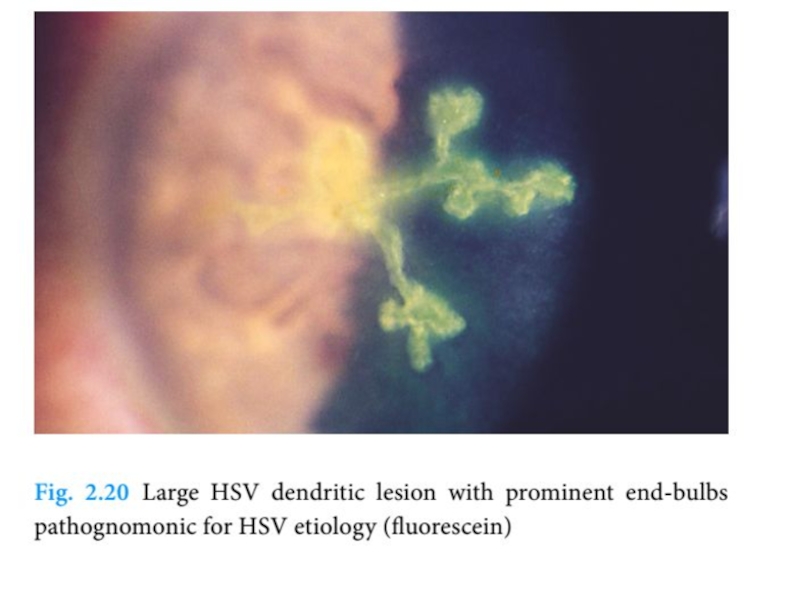

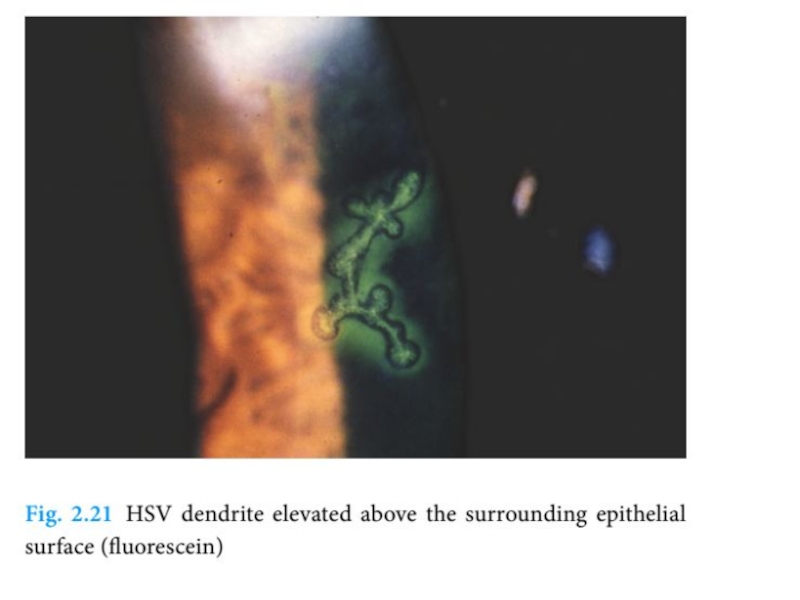

Слайд 12 Epithelial ulcers may cause sensitivity to light,

blurriness, or a

Diagnosis of HSV epithelial keratitis is typically based on

clinical fi ndings. Figure 11.2 shows a typical HSV dendrite.

The distinctive appearance and staining pattern of these

ulcers are important diagnostic points.

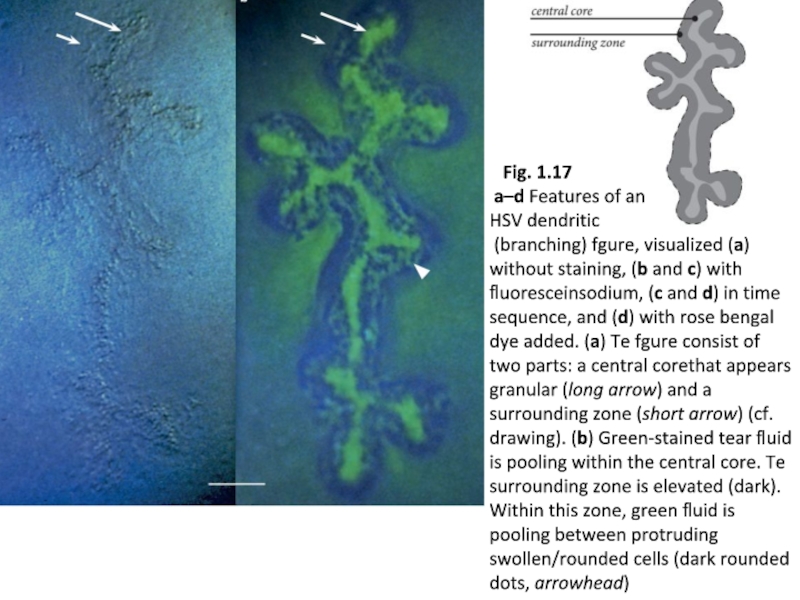

Слайд 17

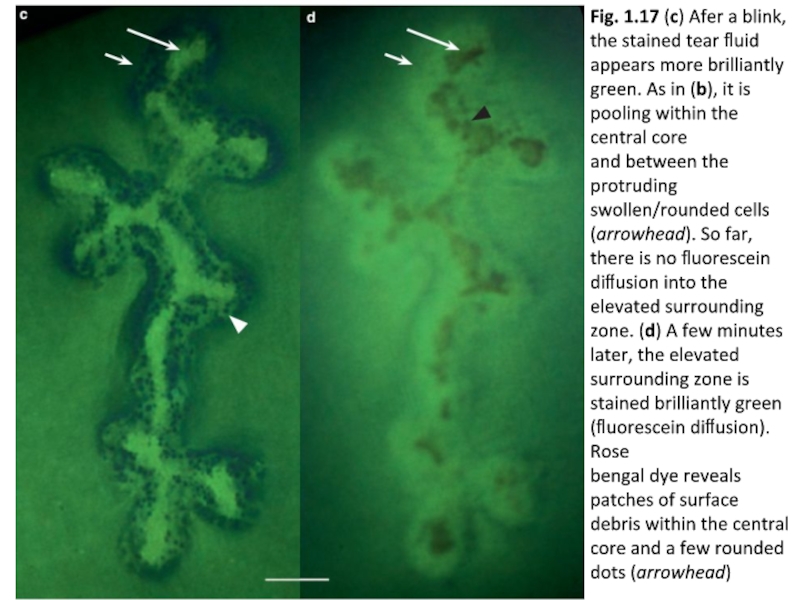

Слайд 18Fig. 1.17 (c) Afer a blink, the stained tear fluid appears

Слайд 20 Epithelial herpes simplex keratitis. (A) Stellate lesions; (B) bed of a dendritic ulcer stained with fuorescein;

Слайд 22 (E) persistent epithelial changes following resolution

of active infection;

(F) residual subepithelial haze

Слайд 28In particular, HSV

culture and PCR are commonly available testing

that can be utilized to aid in the diagnosis of HSV epithelial

keratitis. Serum antibody testing can identify previous HSV

infection. It is important to note that viral samples for lab

testing should be collected prior to epithelial staining since rose bengal is toxic to HSV [ 29 ]. Collecting samples prior to staining will thus reduce false negative test results.

Слайд 29A 5-year-old patient with a history of type I diabetes mellitus

revealed a dendritic epithelial defect with terminal bulbs (Fig. 10.3 ), and she was subsequently diagnosed with HSV epithelial keratitis. Treatment with 400 mg oral acyclovir suspension 4 times daily led to resolution of the dendrite with only minimal corneal scarring.

Слайд 30She returned 12 months later with worsening vision in her right

oral acyclovir.

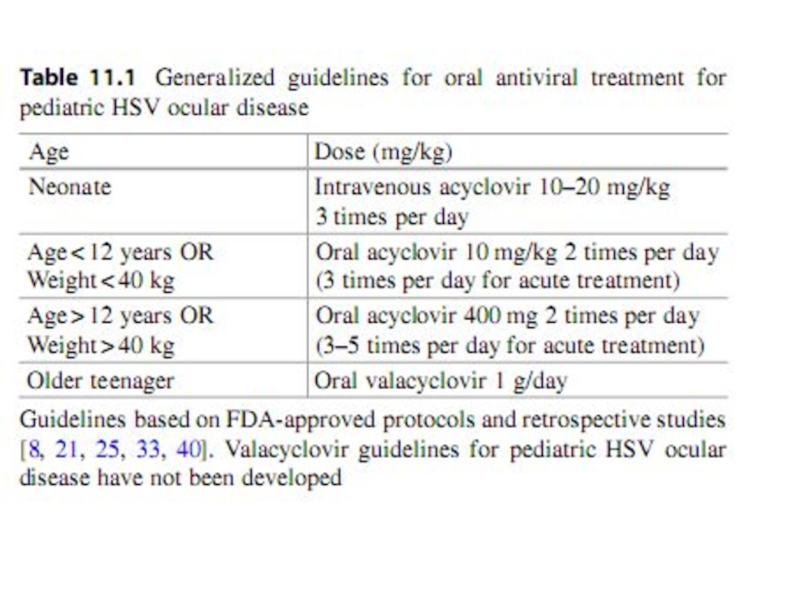

Слайд 31 Although HSV epithelial disease may resolve in some

cases without

resolution, reduce corneal scarring, and diminish stromal

infl ammation. Since the epithelial ulcers are caused by actively

replicating virus, treatment targets the virus itself. Topical

antiviral drugs (trifluridine drops, vidarabine ointment [not

currently commercially available], or ganciclovir gel) have

been shown to be effective in resolving HSV epithelial kerati-

tis. However, instillation of eye drops in small

children may be difficult, and tear dilution from crying could

prevent an effective dose. Oral acyclovir thus provides an

important adjunctive treatment for pediatric HSV epithelial

keratitis, and may provide effective treatment without the use

of a topical antiviral [ 21 ]. See Table 11.1 for acyclovir dosage

considerations.

Слайд 33For infectious HSV epithelial keratitis, topical or oral

antivirals are effective.

of oral acyclovir in epithelial keratitis is 12-40 mg/kg/day in

divided doses up to 40 kg, and the adult dose of 400 mg 5

times daily in children greater than 40 kg [2].

Interestingly, only topical antiviral medication has been

FDA approved for the treatment of HSV keratitis and only

for epithelial keratitis. Evidence-based oral antiviral treatment protocols have been developed for multiple forms of ocular HSV disease from retrospective studies as well as from the prospective studies conducted by the HEDS Group.

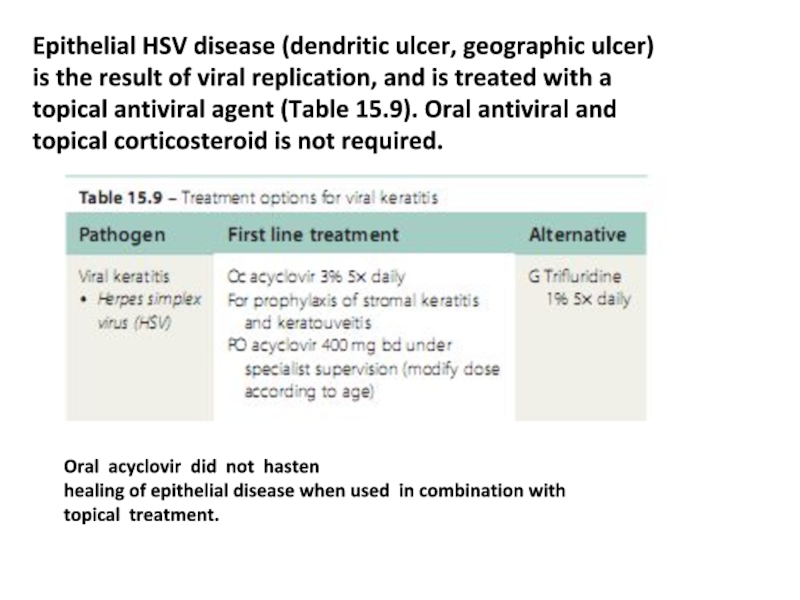

Слайд 35Oral acyclovir did not hasten

healing of epithelial disease when used

topical treatment.

Epithelial HSV disease (dendritic ulcer, geographic ulcer)

is the result of viral replication, and is treated with a

topical antiviral agent (Table 15.9). Oral antiviral and

topical corticosteroid is not required.

Слайд 36Topical corticosteroids are not indicated for

HSV epithelial keratitis and may

[ 24 ]. However, topical corticosteroids play a role in the treat-

ment of HSV stromal keratitis. Stromal keratitis is discussed

in the next section. Some clinicians recommend debridement

of infected epithelial cells to enhance resolution. Historically,

corneal debridement has been described as a method to reduce

the amount of active virus in the epithelium. However, debride-

ment may be less effective than antiviral therapy and may not

signifi cantly improve outcome of antiviral therapy [ 32 ].

Additionally, corneal debridement is diffi cult in children, and

may increase discomfort.

Слайд 37Unfortunately, as described in the introduction, HSV epi-

thelial

faint stromal scar may remain. Recurrent HSV dendritic

ulcers may recur near the scar. Epithelial recurrences increase

the risk of HSV stromal keratitis, an immune-mediated dis-

ease process. Recurrence of HSV keratitis is higher in chil-

dren and is a major management concern [ 21 ]. Thus,

monitoring of children with periodic follow-up examinations

and educating the parents for signs of recurrence are essen-

tial.

Слайд 41 HSV stromal keratitis classically involves an immune-

mediated response to

stroma [ 6 ]. However, complex presentations with mixed pat-

terns of anterior corneal disease and corneal scarring from

multiple recurrences are possible [ 24 ]. Simple HSV stromal

keratitis may present with single or multifocal sub-epithelial

infl ammatory infi ltrates.

Слайд 42Recurrent disease may have corneal

neovascularization accompanying the infl ammatory infi

trates and results in a disease presentation known as interstitial keratitis. Figure 11.3 demonstrates an active interstitial keratitis with stromal infi ltrates and vascularization.

Слайд 43Treatment of

stromal keratitis in children typically involves the use of

cal corticosteroids and oral antivirals. The topical corticoste-

roid is necessary to treat the stromal infl ammation, and the

oral antiviral treats any active viral disease in addition to a

putative contribution in preventing recurrence

Слайд 44The topical corticosteroid may be tapered and the oral antiviral discontinued

minimum amount necessary to control infl ammation.

Слайд 45Valacyclovir may be considered for

older teenage patients with HSV stromal

been FDA approved for long-term treatment (at the 1 g/day

suppressive therapy dose for genital herpes) [ 33 ]. Valacyclovir

is a pro-drug of acyclovir that has an ester moiety that is

removed by esterases to result in the active acyclovir. As a

pro-drug of acyclovir, valacyclovir has greater bioavailability

and would theoretically be expected to have a similar side

effect profi le. Famciclovir has also been approved for long-

term suppressive therapy of genital herpes (at 250 mg twice a

day), so it may also be considered for HSV stromal keratitis

in older teenage patients [ 34 ]. However, famciclovir is not

FDA approved for children.

Слайд 46Epithelial keratitis later followed by stromal keratitis or concomitant epithelial

In cases with concomitant epithelial disease, topical treatment is generally added for the fi rst 2 weeks.

Слайд 49The Herpes Eye Disease Study Group treatment guidelines are as follows:

•

• There is no additional effect of oral acyclovir over topical steroid and F3T when treating stromal keratitis.

• After epithelial HSV a 3-week course of oral acyclovir (400 mg 5 times a day) does not prevent stromal disease in the subsequent year.

• Prophylactic treatment with acyclovir (400 mg bd) reduces epithelial recurrences and stromal recurrences in patients with prior stromal disease by about 50% over 12 months. Prophylactic treatment is usually restricted

to patients with bilateral disease, prior HSV keratitis in atopes, or the immunosuppressed, especially following

corneal surgery.

Слайд 51Typical features of a neonatal HSV infection include localized external lesions

herpes affecting internal organs, and central nervous system

infection (encephalitis). An infected infant may display sev-

eral of these features. Ocular herpes in the newborn typically

appears as periorbital skin vesicles, blepharoconjunctivitis,

keratitis, anterior uveitis, chorioretinitis, and congenital cata-

racts [ 3 , 39 ]. Importantly, a dilated fundus examination

should be performed in any neonate with suspected HSV infection. Since herpes infections may resemble other neona-

tal infections, laboratory tests (e.g., fl uorescein antibody tests,

herpes culture, or PCR testing) should be performed in all

cases of suspected neonatal herpes [ 28 ]. While awaiting lab

results, the newborn should be empirically treated with intra-

venous acyclovir.

Слайд 52 Overall prognosis of neonatal ocular HSV infection

treated with intravenous

However, mortality is higher in newborns with disseminated

infection or CNS disease [ 28 ]. Visual outcome is poorer

when corneal herpetic disease causes scarring. Infants must

also be monitored closely for evidence of recurrent disease.

Infants with recurrent HSV keratitis are typically followed

longitudinally by an infectious disease specialist.

Additionally, longitudinal follow-up by a pediatric ophthal-

mologist is important due to the risk of amblyopia develop-

ment associated with recurrent HSV keratitis. If there is

recurrent neonatal ocular HSV infection, higher oral doses of

acyclovir may be necessary.

![Although HSV epithelial disease may resolve in some cases without intervention [ 30 ],](/img/tmb/5/449630/b66e1855d5d9782b80db429ea9ca139a-800x.jpg)