Esq.

Jana Kolarik Anderson, Esq. Alan H. Einhorn, Esq.

- Главная

- Разное

- Дизайн

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Аналитика

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Красота и здоровье

- Финансы

- Государство

- Путешествия

- Спорт

- Недвижимость

- Армия

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Legal Update: 340B, Physician Compensation, and Recent Stark Developments презентация

Содержание

- 1. Legal Update: 340B, Physician Compensation, and Recent Stark Developments

- 2. 340B Drug Pricing Program: Recent Developments Elizabeth

- 3. 340B Drug Pricing Program: Overview Federal drug

- 4. ACA’s Impact on the 340B Drug Pricing

- 5. Entity Eligibility Hospital outpatient departments Only those

- 6. Diversion of 340B Drugs Covered entities may

- 7. Proposed Omnibus Guidance Issued as interpretive guidance

- 8. Changes to Current Patient Definition Current Patient

- 9. Proposed 340B Patient Definition Patient eligibility determined

- 10. Proposed 340B Patient Definition (cont’d) (2) The

- 11. Proposed 340B Patient Definition (cont’d) (3) The

- 12. Proposed 340B Patient Definition (cont’d) (4) The

- 13. Proposed 340B Patient Definition (cont’d) (5) The

- 14. Proposed 340B Patient Definition (cont’d) (6) The

- 15. Recent Legislation: Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015

- 16. Recent Legislation (cont’d) Legislation does not address

- 17. MedPAC: Proposed Medicare Payment Cuts for 340B

- 18. Impending Changes in 2016: HHS Regulatory Agenda

- 19. Physician Compensation & FDA/DOJ Enforcement Actions Related

- 20. Physician Compensation – AKBS Safe Harbor &

- 21. Physician Compensation – AKBS Safe Harbor &

- 22. Physician Compensation – AKBS Safe Harbor &

- 23. Physician Compensation – Stark Law Cases Recent

- 24. Physician Compensation – Stark Law Cases In

- 25. Physician Compensation – Stark Law Cases (cont’d)

- 26. New OIG Litigation Team In Summer

- 27. FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs There

- 28. FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs (cont’d)

- 29. FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs (cont’d)

- 30. FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs (cont’d)

- 31. FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs -

- 32. FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs -

- 33. The Recent Stark Law Changes Alan H.

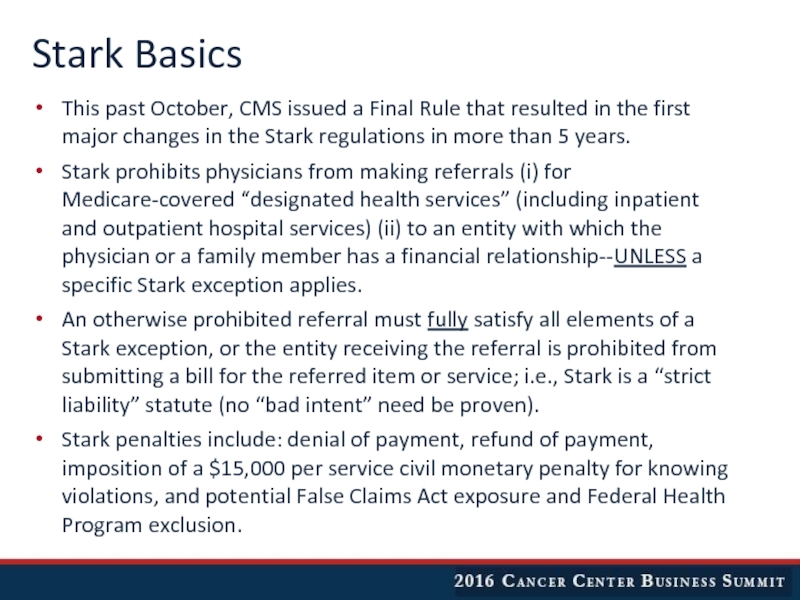

- 34. Stark Basics This past October, CMS

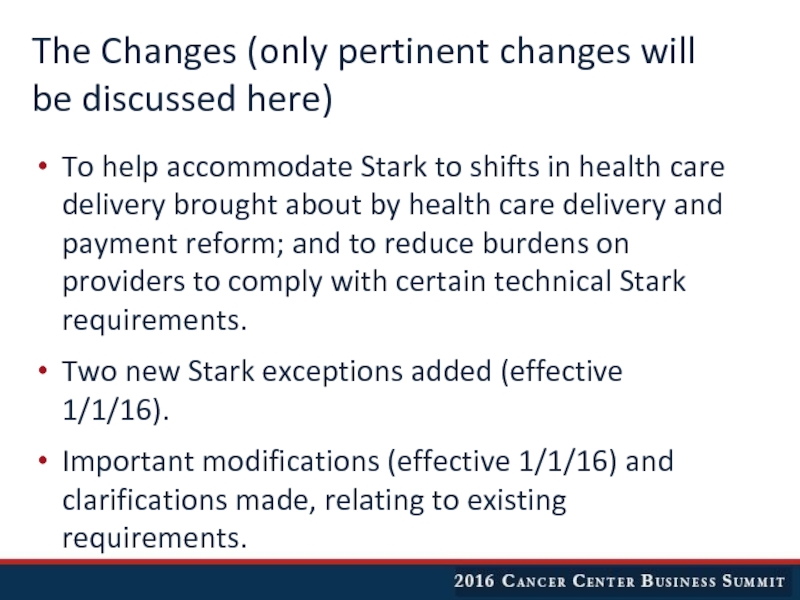

- 35. The Changes (only pertinent changes will be

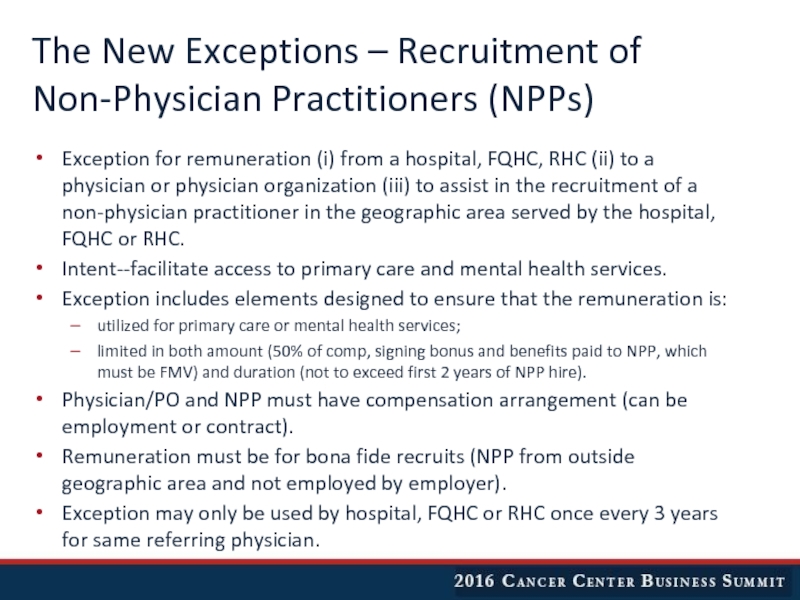

- 36. The New Exceptions – Recruitment of Non-Physician

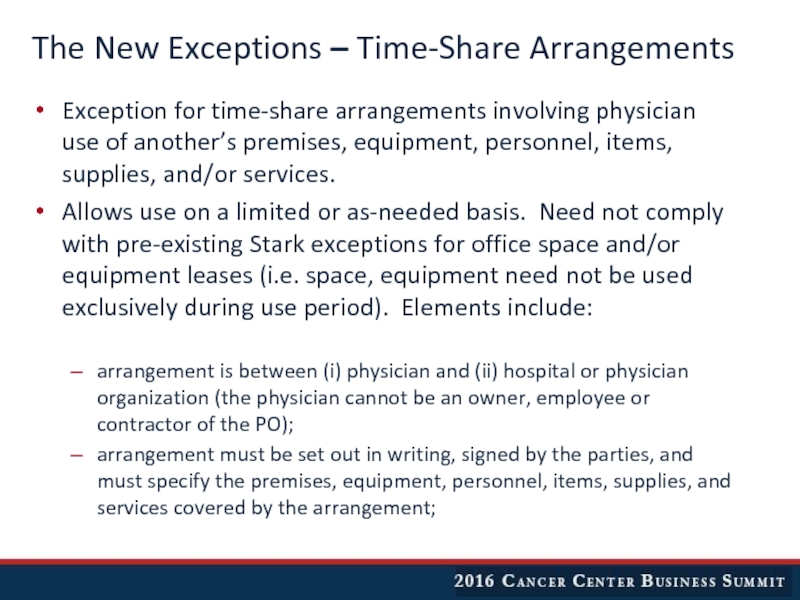

- 37. The New Exceptions – Time-Share Arrangements Exception

- 38. The New Exceptions – Time-Share Arrangements (cont’d)

- 39. Modifications – Holdovers Final Rule modifies current

- 40. Modifications – Signatures Final Rule extends time-frame

- 41. Modifications – Signatures (cont’d) NOTE: to utilize

- 42. Clarifications Among the more significant “products” of

- 43. Clarifications – “At Least One Year”. The

- 44. Questions?

Слайд 1Legal Update: 340B, Physician Compensation, and Recent Stark Developments

Elizabeth S. Elson,

Слайд 2340B Drug Pricing Program:

Recent Developments

Elizabeth S. Elson, Esq.

Of Counsel, Foley &

Lardner LLP

February 25, 2016

February 25, 2016

Слайд 3340B Drug Pricing Program:

Overview

Federal drug pricing program

Operated by the Office of

Pharmacy Affairs (“OPA”) in the Health Resources and Services Administration (“HRSA”).

Drug manufacturers are required to provide significant discounts to participating “covered entities” on covered outpatient drugs provided to eligible “patients”

Covered entities include health care providers such as FQHCs, specialized clinics, and DSH hospitals (with DSH > 11.75%).

Intended to provide financial relief to facilities that provide care to the medically underserved.

Drug manufacturers are required to provide significant discounts to participating “covered entities” on covered outpatient drugs provided to eligible “patients”

Covered entities include health care providers such as FQHCs, specialized clinics, and DSH hospitals (with DSH > 11.75%).

Intended to provide financial relief to facilities that provide care to the medically underserved.

Слайд 4ACA’s Impact on the 340B Drug Pricing Program

Affordable Care Act expanded

participation

to new covered entities:

Children's hospitals with Medicare DSH > 11.75%;

Freestanding cancer hospitals with Medicare DSH > 11.75%;

Critical access hospitals (CAHs);

Rural referral centers with a Medicare DSH > 8%;

Sole community hospitals with a Medicare DSH > 8%.

It also created increased program integrity efforts (e.g., annual recertification, increased auditing) and new sanction authority for compliance violations.

Children's hospitals with Medicare DSH > 11.75%;

Freestanding cancer hospitals with Medicare DSH > 11.75%;

Critical access hospitals (CAHs);

Rural referral centers with a Medicare DSH > 8%;

Sole community hospitals with a Medicare DSH > 8%.

It also created increased program integrity efforts (e.g., annual recertification, increased auditing) and new sanction authority for compliance violations.

Слайд 5Entity Eligibility

Hospital outpatient departments

Only those locations listed as a reimbursable center

on the hospital’s most recently filed Medicare cost report are considered part of a covered entity hospital;

Delays waiting for cost reports to be filed;

Outpatient locations must meet Medicare provider-based standards.

Participation is limited to the covered entity, even if it is part of a larger health system or entity.

Physician groups are not covered entities.

Delays waiting for cost reports to be filed;

Outpatient locations must meet Medicare provider-based standards.

Participation is limited to the covered entity, even if it is part of a larger health system or entity.

Physician groups are not covered entities.

Слайд 6Diversion of 340B Drugs

Covered entities may not resell or otherwise transfer

medications purchased under the 340B Program to a person who is not a “patient” of the covered entity.

Definition of a 340B patient not defined in statute, but set forth in HRSA guidance.

Definition of a 340B patient not defined in statute, but set forth in HRSA guidance.

Слайд 7Proposed Omnibus Guidance

Issued as interpretive guidance on August 28, 2015.

Over 1,000

comments received.

Enforceability may depend on consistency with 340B statute and amount of deference given to HHS/HRSA.

Impact of orphan drug litigation.

Potential to be applied by HRSA prior to finalization.

Enforceability may depend on consistency with 340B statute and amount of deference given to HHS/HRSA.

Impact of orphan drug litigation.

Potential to be applied by HRSA prior to finalization.

Слайд 8Changes to Current Patient Definition

Current Patient Definition:

Based on covered entity’s

relationship with the individual (as evidenced by maintaining medical records), and its responsibility for care (through employment, contractual, or other arrangements with health care providers);

Gray areas/flexibility to meet these standards.

Proposed Changes

Proposes more detailed/specific requirements;

Would exclude some individuals currently treated as 340B patients;

Would introduce new complexity and administrative burden;

Consistent with the 340B statute?

Gray areas/flexibility to meet these standards.

Proposed Changes

Proposes more detailed/specific requirements;

Would exclude some individuals currently treated as 340B patients;

Would introduce new complexity and administrative burden;

Consistent with the 340B statute?

Слайд 9Proposed 340B Patient Definition

Patient eligibility determined on a per prescription or

per order basis and must meet all of these criteria:

(1) The individual receives a health care service at a covered entity site which is registered for the 340B Program and listed on the public 340B Program database;

Removes support for referral arrangements for follow up/specialty care outside the covered entity.

(1) The individual receives a health care service at a covered entity site which is registered for the 340B Program and listed on the public 340B Program database;

Removes support for referral arrangements for follow up/specialty care outside the covered entity.

Слайд 10Proposed 340B Patient Definition

(cont’d)

(2) The individual receives a health care service

from

a health care provider employed by the

covered entity or who is an independent contractor of the covered entity such that the covered entity may bill for services on behalf of the provider;

Privileges/Credentials not enough;

New requirement that covered entity must be able to bill for professional services.

Privileges/Credentials not enough;

New requirement that covered entity must be able to bill for professional services.

Слайд 11Proposed 340B Patient Definition

(cont’d)

(3) The individual receives a drug that is

ordered or prescribed by the covered entity provider as a result of the service described in (2). The individual will not be considered a patient of the covered entity if the only health care received by the individual from the covered entity is the infusion of a drug or the dispensing of a drug;

Necessary relationship between 340B drug ordered and type of service received;

Exclusion of infusion drugs.

Necessary relationship between 340B drug ordered and type of service received;

Exclusion of infusion drugs.

Слайд 12Proposed 340B Patient Definition

(cont’d)

(4) The individual receives a health care service

that is consistent with the covered entity’s scope of grant, project or contract;

Hospitals generally exempt;

Consistent with current definition.

Hospitals generally exempt;

Consistent with current definition.

Слайд 13Proposed 340B Patient Definition

(cont’d)

(5) The individual is classified as an outpatient

when the drug is ordered or prescribed, as determined by status when billed to payor;

Elimination of ability to purchase 340B drugs for discharged inpatients; reduction of contract pharmacy purchases;

Patient’s payor billing status critical; administratively burdensome/challenging.

Elimination of ability to purchase 340B drugs for discharged inpatients; reduction of contract pharmacy purchases;

Patient’s payor billing status critical; administratively burdensome/challenging.

Слайд 14Proposed 340B Patient Definition

(cont’d)

(6) The individual has a relationship with the

covered entity such that the covered entity

maintains access to auditable health care records which demonstrate that the covered entity has a provider-to-patient relationship, that the responsibility for that care is with the covered entity, and that each element of this patient definition is met for each 340B drug;

Generally consistent with current definition.

Generally consistent with current definition.

Слайд 15Recent Legislation: Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (“Section 603”)

Budget bill enacted

in November 2015 includes language excluding certain hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) from Medicare OPPS;

Applies to new facilities (grandfathering of facilities that billed Medicare prior to the date of enactment); payment change effective 1/1/17;

Applies only to off-campus facilities;

Does not apply to dedicated emergency departments.

Goal is to promote “site neutral” payment – level playing field with physician offices, ambulatory surgery centers, etc.

Applies to new facilities (grandfathering of facilities that billed Medicare prior to the date of enactment); payment change effective 1/1/17;

Applies only to off-campus facilities;

Does not apply to dedicated emergency departments.

Goal is to promote “site neutral” payment – level playing field with physician offices, ambulatory surgery centers, etc.

Слайд 16Recent Legislation (cont’d)

Legislation does not address 340B; arguably has no direct

impact;

Off-campus facilities may still qualify as “provider-based” and be included on hospital’s cost report.

May in effect reduce scope of 340 Program if it leads to fewer HOPDs.

340B eligibility of new HOPDs may depend on how Section 603 is implemented by CMS (e.g., through enrollment process, cost report, coding/modifier, other?)

More likely to have adverse impact if implemented through enrollment/cost report than through payment modifier only.

Off-campus facilities may still qualify as “provider-based” and be included on hospital’s cost report.

May in effect reduce scope of 340 Program if it leads to fewer HOPDs.

340B eligibility of new HOPDs may depend on how Section 603 is implemented by CMS (e.g., through enrollment process, cost report, coding/modifier, other?)

More likely to have adverse impact if implemented through enrollment/cost report than through payment modifier only.

Слайд 17MedPAC: Proposed Medicare Payment Cuts for 340B Drugs

Another recent development was

MedPAC’s recommendation in January to cut Medicare Part B rates by 10% for 340B drugs purchased by 340B covered entity hospitals.

Currently hospitals retain difference between 340B acquisition price and Medicare payment rate.

If approved by Congress, would result in significant cut in 340B hospitals’ savings and operational challenges in implementing.

Currently hospitals retain difference between 340B acquisition price and Medicare payment rate.

If approved by Congress, would result in significant cut in 340B hospitals’ savings and operational challenges in implementing.

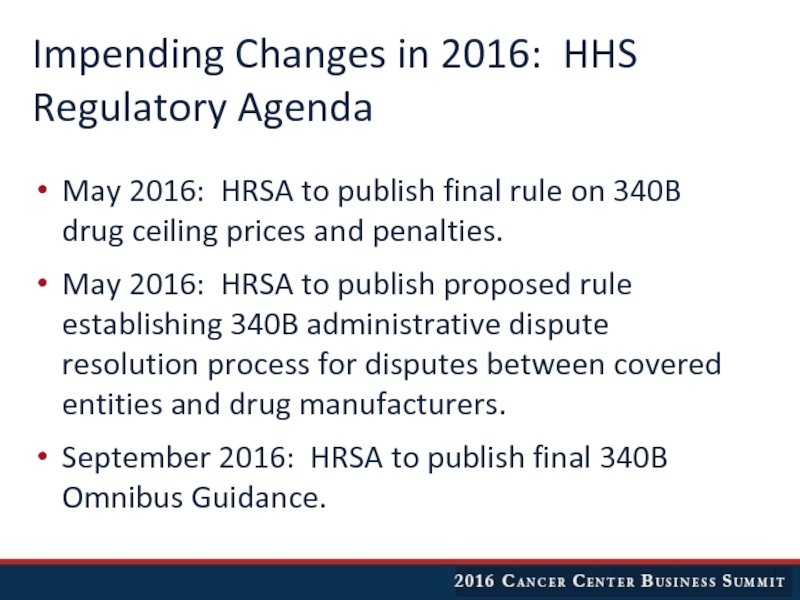

Слайд 18Impending Changes in 2016: HHS Regulatory Agenda

May 2016: HRSA to publish

final rule on 340B drug ceiling prices and penalties.

May 2016: HRSA to publish proposed rule establishing 340B administrative dispute resolution process for disputes between covered entities and drug manufacturers.

September 2016: HRSA to publish final 340B Omnibus Guidance.

May 2016: HRSA to publish proposed rule establishing 340B administrative dispute resolution process for disputes between covered entities and drug manufacturers.

September 2016: HRSA to publish final 340B Omnibus Guidance.

Слайд 19Physician Compensation & FDA/DOJ Enforcement Actions Related to Oncology Drugs

Jana Kolarik

Anderson, Esq.

Partner, Foley & Lardner LLP

February 25, 2016

Partner, Foley & Lardner LLP

February 25, 2016

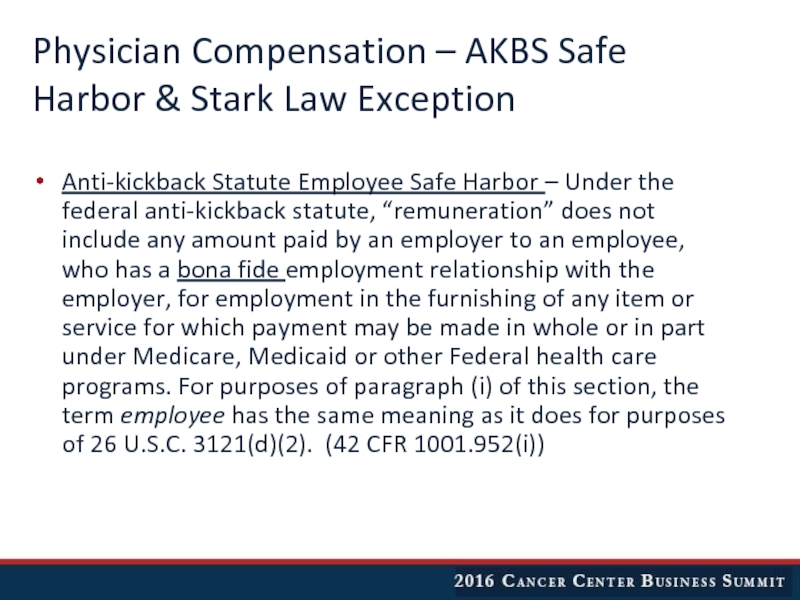

Слайд 20Physician Compensation – AKBS Safe Harbor & Stark Law Exception

Anti-kickback Statute

Employee Safe Harbor – Under the federal anti-kickback statute, “remuneration” does not include any amount paid by an employer to an employee, who has a bona fide employment relationship with the employer, for employment in the furnishing of any item or service for which payment may be made in whole or in part under Medicare, Medicaid or other Federal health care programs. For purposes of paragraph (i) of this section, the term employee has the same meaning as it does for purposes of 26 U.S.C. 3121(d)(2). (42 CFR 1001.952(i))

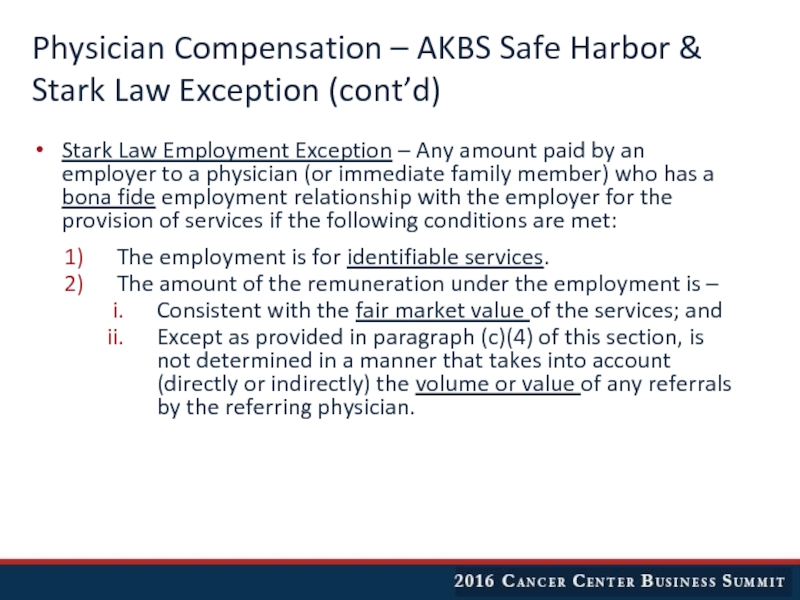

Слайд 21Physician Compensation – AKBS Safe Harbor & Stark Law Exception (cont’d)

Stark

Law Employment Exception – Any amount paid by an employer to a physician (or immediate family member) who has a bona fide employment relationship with the employer for the provision of services if the following conditions are met:

The employment is for identifiable services.

The amount of the remuneration under the employment is –

Consistent with the fair market value of the services; and

Except as provided in paragraph (c)(4) of this section, is not determined in a manner that takes into account (directly or indirectly) the volume or value of any referrals by the referring physician.

The employment is for identifiable services.

The amount of the remuneration under the employment is –

Consistent with the fair market value of the services; and

Except as provided in paragraph (c)(4) of this section, is not determined in a manner that takes into account (directly or indirectly) the volume or value of any referrals by the referring physician.

Слайд 22Physician Compensation – AKBS Safe Harbor & Stark Law Exception (cont’d)

The

remuneration is provided under an agreement that would be commercially reasonable even if no referrals were made to the employer.

Paragraph (c)(2)(ii) of this section does not prohibit payment of remuneration in the form of a productivity bonus based on services performed personally by the physician (or immediate family member of the physician).

(42 CFR 411.357(c))

Paragraph (c)(2)(ii) of this section does not prohibit payment of remuneration in the form of a productivity bonus based on services performed personally by the physician (or immediate family member of the physician).

(42 CFR 411.357(c))

Слайд 23Physician Compensation – Stark Law Cases

Recent Cases – United States ex.

rel. Drakeford v. Tuomey (4th Cir. 2012) and United States v. Halifax Hosp. Med. Ctr. (M.D. Fla. 2013), and United States ex rel. Parikh et al. v. Citizens Medical Center (S.D. Tex. 2015) – have shown the government’s interest in Stark Law enforcement actions against hospital-physician compensation arrangements.

Tuomey had a jury verdict of $237 million, which was eventually lowered to $72,406,860 when Tuomey was acquired by another health system.

Halifax settled for $85 million.

In Tuomey and Halifax, a Department of Justice (DOJ) valuation expert took the position in litigation that physician arrangements involving departments that “lose” money are commercially unreasonable (without offering any statutory or regulatory basis for the position).

Tuomey had a jury verdict of $237 million, which was eventually lowered to $72,406,860 when Tuomey was acquired by another health system.

Halifax settled for $85 million.

In Tuomey and Halifax, a Department of Justice (DOJ) valuation expert took the position in litigation that physician arrangements involving departments that “lose” money are commercially unreasonable (without offering any statutory or regulatory basis for the position).

Слайд 24Physician Compensation – Stark Law Cases

In Halifax, the district court entered

partial summary judgment after finding that the productivity bonuses paid to six (6) employed oncologists varied based on the volume of DHS referrals and, therefore, were inconsistent with the requirements of the employment exception.

The Halifax-employed oncologists were eligible for productivity bonuses that were paid from a pool composed of 15% of the operating margin of the hospital’s oncology program.

The Halifax-employed oncologists were eligible for productivity bonuses that were paid from a pool composed of 15% of the operating margin of the hospital’s oncology program.

Слайд 25Physician Compensation – Stark Law Cases

(cont’d)

The Halifax court held that because

the bonus pool included revenues from DHS services that were not personally performed by the oncologists, the amount of the bonus pool was based in part on the volume or value of the employed oncologists’ referrals to Halifax.

In Citizens Medical Center, the settlement was for $21.75 million, related to allegations that the hospital paid several cardiologists compensation that exceed fair market value (doubling their income despite the practice’s losses) and paid bonuses to emergency room physician that improperly took into account the value of their cardiology referrals.

In Citizens Medical Center, the settlement was for $21.75 million, related to allegations that the hospital paid several cardiologists compensation that exceed fair market value (doubling their income despite the practice’s losses) and paid bonuses to emergency room physician that improperly took into account the value of their cardiology referrals.

Слайд 26New OIG Litigation Team

In Summer 2015, representatives from the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General (OIG) announced the creation of an OIG litigation team that will focus specifically on civil monetary penalties (e.g., resulting from kickback arrangements) and exclusion cases.

The understood focus of that team will be physicians and practices which have, for the most part, been ignored in anti-kickback enforcement actions brought by the OIG.

The understood focus of that team will be physicians and practices which have, for the most part, been ignored in anti-kickback enforcement actions brought by the OIG.

Слайд 27FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs

There has been a series of

DOJ/FDA enforcement actions from 2013 through 2015 related to adulterated/counterfeit oncology drugs.

The cases related to drugs -

ordered from various foreign sources, including companies in Canada, Great Britain, Pakistan, India and Turkey that were not licensed to distribute drugs into the United States,

that were not FDA approved, and

that did not bear appropriate labeling (e.g., ”Rx Only” or the National Drug Code/NDC numbers).

As such, the drugs were not lawful to sell/buy in the United States or bill to the Federal health care programs.

The actions were brought against pharmacies, drug distributors and their owners and physicians.

The cases related to drugs -

ordered from various foreign sources, including companies in Canada, Great Britain, Pakistan, India and Turkey that were not licensed to distribute drugs into the United States,

that were not FDA approved, and

that did not bear appropriate labeling (e.g., ”Rx Only” or the National Drug Code/NDC numbers).

As such, the drugs were not lawful to sell/buy in the United States or bill to the Federal health care programs.

The actions were brought against pharmacies, drug distributors and their owners and physicians.

Слайд 28FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs

(cont’d)

The FDA/DOJ joint enforcement cases were

civil and criminal cases with criminal conspiracy to import merchandise contrary to law and health care fraud counts.

Some examples of settlements included –

February 24, 2015 settlement –

Prabhjit Purewal, M.D. agreed to pay $550,000 to the United States to settle allegations that he defrauded Medicare, Tricare and Medicaid by billing these pubic insurers for chemotherapy drugs that the FDA had not approved for use.

Dr. Purewal purchased the drugs from Warwick Healthcare Solutions (aka Richard’s Pharma), administered the drugs to his patients and improperly sought and received reimbursement for the drugs from the Federal health care programs.

Warwick, a former UK-based drug distributor, did not have a license to distribute drugs in the U.S., and many of the drugs Dr. Purewal purchased from Warwick were not FDA approved.

Some examples of settlements included –

February 24, 2015 settlement –

Prabhjit Purewal, M.D. agreed to pay $550,000 to the United States to settle allegations that he defrauded Medicare, Tricare and Medicaid by billing these pubic insurers for chemotherapy drugs that the FDA had not approved for use.

Dr. Purewal purchased the drugs from Warwick Healthcare Solutions (aka Richard’s Pharma), administered the drugs to his patients and improperly sought and received reimbursement for the drugs from the Federal health care programs.

Warwick, a former UK-based drug distributor, did not have a license to distribute drugs in the U.S., and many of the drugs Dr. Purewal purchased from Warwick were not FDA approved.

Слайд 29FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs

(cont’d)

February 21, 2014 –

Alvarado Medical

Plaza Pharmacy, Inc. was sentenced to repay Medicare over $1 million and to pay a $10,000 fine following its conviction of federal health care fraud for billing Medicare for unapproved oncology drugs.

The pharmacy admitted that between May 2010 and June 2011, it ordered $752,688 of prescription oncology drugs from Quality Specialty Products (QSP) in Canada.

The drugs ordered from QSP were unapproved versions of drugs sold in the U.S. as Avastin, Eloxatin, Gemzar, Neupogen, Rituxin, Taxotere and Zometa, which were shipped from Canada to the defendant in San Diego.

The pharmacy admitted that between May 2010 and June 2011, it ordered $752,688 of prescription oncology drugs from Quality Specialty Products (QSP) in Canada.

The drugs ordered from QSP were unapproved versions of drugs sold in the U.S. as Avastin, Eloxatin, Gemzar, Neupogen, Rituxin, Taxotere and Zometa, which were shipped from Canada to the defendant in San Diego.

Слайд 30FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs (cont’d)

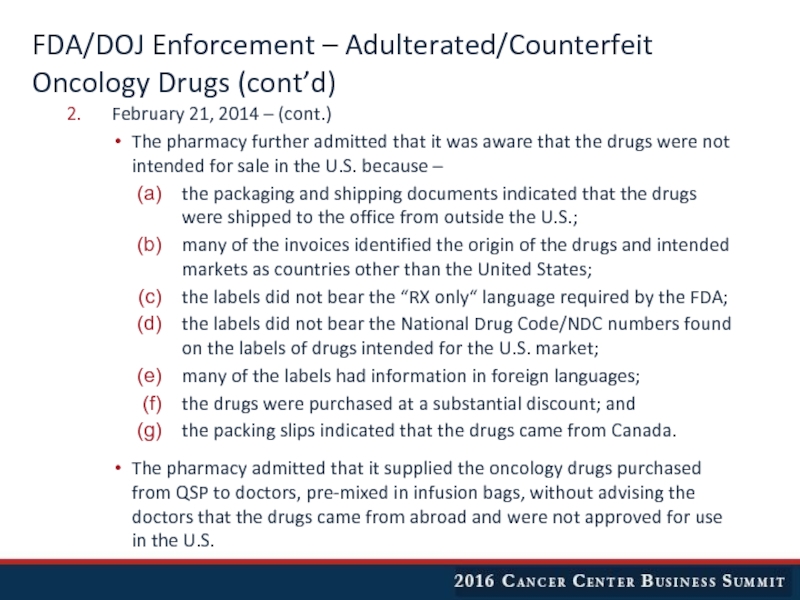

February 21, 2014 – (cont.)

The

pharmacy further admitted that it was aware that the drugs were not intended for sale in the U.S. because –

the packaging and shipping documents indicated that the drugs were shipped to the office from outside the U.S.;

many of the invoices identified the origin of the drugs and intended markets as countries other than the United States;

the labels did not bear the “RX only“ language required by the FDA;

the labels did not bear the National Drug Code/NDC numbers found on the labels of drugs intended for the U.S. market;

many of the labels had information in foreign languages;

the drugs were purchased at a substantial discount; and

the packing slips indicated that the drugs came from Canada.

The pharmacy admitted that it supplied the oncology drugs purchased from QSP to doctors, pre-mixed in infusion bags, without advising the doctors that the drugs came from abroad and were not approved for use in the U.S.

the packaging and shipping documents indicated that the drugs were shipped to the office from outside the U.S.;

many of the invoices identified the origin of the drugs and intended markets as countries other than the United States;

the labels did not bear the “RX only“ language required by the FDA;

the labels did not bear the National Drug Code/NDC numbers found on the labels of drugs intended for the U.S. market;

many of the labels had information in foreign languages;

the drugs were purchased at a substantial discount; and

the packing slips indicated that the drugs came from Canada.

The pharmacy admitted that it supplied the oncology drugs purchased from QSP to doctors, pre-mixed in infusion bags, without advising the doctors that the drugs came from abroad and were not approved for use in the U.S.

Слайд 31FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs - (cont’d)

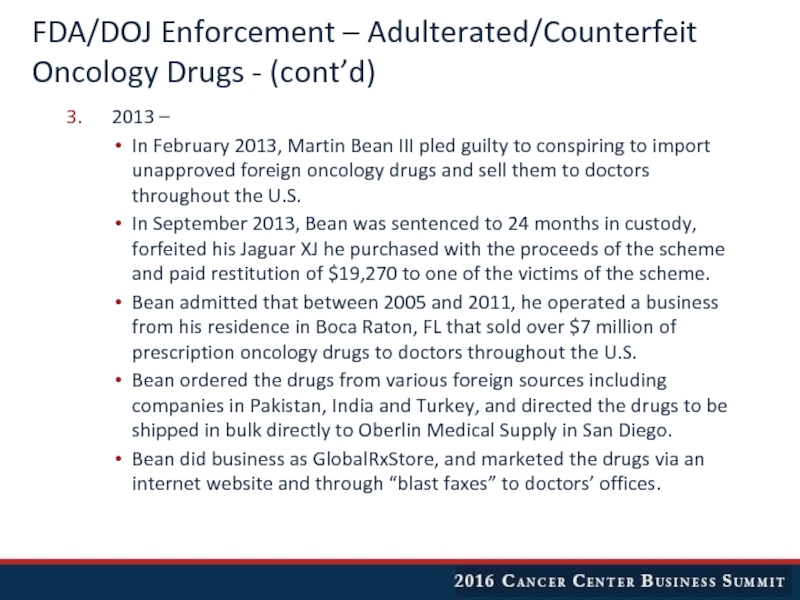

2013 –

In February

2013, Martin Bean III pled guilty to conspiring to import unapproved foreign oncology drugs and sell them to doctors throughout the U.S.

In September 2013, Bean was sentenced to 24 months in custody, forfeited his Jaguar XJ he purchased with the proceeds of the scheme and paid restitution of $19,270 to one of the victims of the scheme.

Bean admitted that between 2005 and 2011, he operated a business from his residence in Boca Raton, FL that sold over $7 million of prescription oncology drugs to doctors throughout the U.S.

Bean ordered the drugs from various foreign sources including companies in Pakistan, India and Turkey, and directed the drugs to be shipped in bulk directly to Oberlin Medical Supply in San Diego.

Bean did business as GlobalRxStore, and marketed the drugs via an internet website and through “blast faxes” to doctors’ offices.

In September 2013, Bean was sentenced to 24 months in custody, forfeited his Jaguar XJ he purchased with the proceeds of the scheme and paid restitution of $19,270 to one of the victims of the scheme.

Bean admitted that between 2005 and 2011, he operated a business from his residence in Boca Raton, FL that sold over $7 million of prescription oncology drugs to doctors throughout the U.S.

Bean ordered the drugs from various foreign sources including companies in Pakistan, India and Turkey, and directed the drugs to be shipped in bulk directly to Oberlin Medical Supply in San Diego.

Bean did business as GlobalRxStore, and marketed the drugs via an internet website and through “blast faxes” to doctors’ offices.

Слайд 32FDA/DOJ Enforcement – Adulterated/Counterfeit Oncology Drugs - (cont’d)

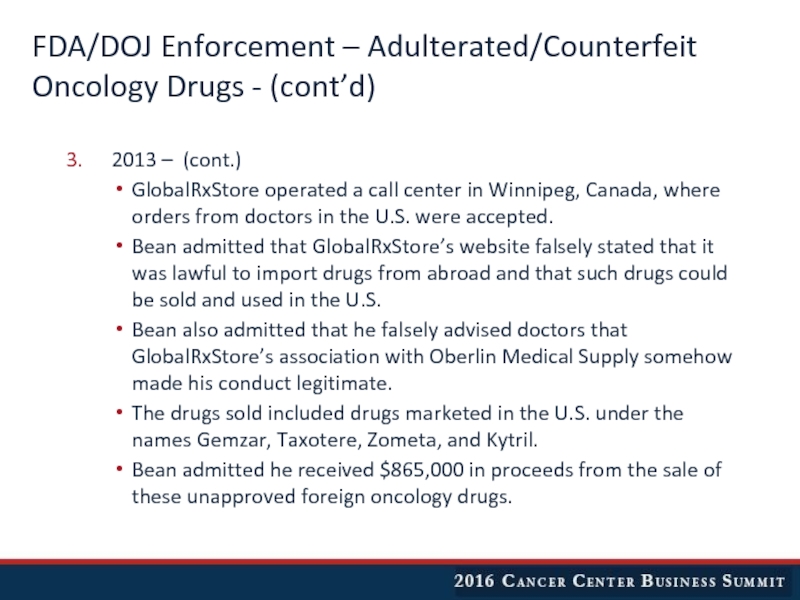

2013 – (cont.)

GlobalRxStore operated

a call center in Winnipeg, Canada, where orders from doctors in the U.S. were accepted.

Bean admitted that GlobalRxStore’s website falsely stated that it was lawful to import drugs from abroad and that such drugs could be sold and used in the U.S.

Bean also admitted that he falsely advised doctors that GlobalRxStore’s association with Oberlin Medical Supply somehow made his conduct legitimate.

The drugs sold included drugs marketed in the U.S. under the names Gemzar, Taxotere, Zometa, and Kytril.

Bean admitted he received $865,000 in proceeds from the sale of these unapproved foreign oncology drugs.

Bean admitted that GlobalRxStore’s website falsely stated that it was lawful to import drugs from abroad and that such drugs could be sold and used in the U.S.

Bean also admitted that he falsely advised doctors that GlobalRxStore’s association with Oberlin Medical Supply somehow made his conduct legitimate.

The drugs sold included drugs marketed in the U.S. under the names Gemzar, Taxotere, Zometa, and Kytril.

Bean admitted he received $865,000 in proceeds from the sale of these unapproved foreign oncology drugs.

Слайд 33The Recent Stark Law Changes

Alan H. Einhorn, Esq.

Of Counsel, Foley &

Lardner LLP

February 25, 2016

February 25, 2016

Слайд 34Stark Basics

This past October, CMS issued a Final Rule that resulted

in the first major changes in the Stark regulations in more than 5 years.

Stark prohibits physicians from making referrals (i) for Medicare-covered “designated health services” (including inpatient and outpatient hospital services) (ii) to an entity with which the physician or a family member has a financial relationship--UNLESS a specific Stark exception applies.

An otherwise prohibited referral must fully satisfy all elements of a Stark exception, or the entity receiving the referral is prohibited from submitting a bill for the referred item or service; i.e., Stark is a “strict liability” statute (no “bad intent” need be proven).

Stark penalties include: denial of payment, refund of payment, imposition of a $15,000 per service civil monetary penalty for knowing violations, and potential False Claims Act exposure and Federal Health Program exclusion.

Stark prohibits physicians from making referrals (i) for Medicare-covered “designated health services” (including inpatient and outpatient hospital services) (ii) to an entity with which the physician or a family member has a financial relationship--UNLESS a specific Stark exception applies.

An otherwise prohibited referral must fully satisfy all elements of a Stark exception, or the entity receiving the referral is prohibited from submitting a bill for the referred item or service; i.e., Stark is a “strict liability” statute (no “bad intent” need be proven).

Stark penalties include: denial of payment, refund of payment, imposition of a $15,000 per service civil monetary penalty for knowing violations, and potential False Claims Act exposure and Federal Health Program exclusion.

Слайд 35The Changes (only pertinent changes will be discussed here)

To help accommodate

Stark to shifts in health care delivery brought about by health care delivery and payment reform; and to reduce burdens on providers to comply with certain technical Stark requirements.

Two new Stark exceptions added (effective 1/1/16).

Important modifications (effective 1/1/16) and clarifications made, relating to existing requirements.

Two new Stark exceptions added (effective 1/1/16).

Important modifications (effective 1/1/16) and clarifications made, relating to existing requirements.

Слайд 36The New Exceptions – Recruitment of Non-Physician Practitioners (NPPs)

Exception for remuneration

(i) from a hospital, FQHC, RHC (ii) to a physician or physician organization (iii) to assist in the recruitment of a non-physician practitioner in the geographic area served by the hospital, FQHC or RHC.

Intent--facilitate access to primary care and mental health services.

Exception includes elements designed to ensure that the remuneration is:

utilized for primary care or mental health services;

limited in both amount (50% of comp, signing bonus and benefits paid to NPP, which must be FMV) and duration (not to exceed first 2 years of NPP hire).

Physician/PO and NPP must have compensation arrangement (can be employment or contract).

Remuneration must be for bona fide recruits (NPP from outside geographic area and not employed by employer).

Exception may only be used by hospital, FQHC or RHC once every 3 years for same referring physician.

Intent--facilitate access to primary care and mental health services.

Exception includes elements designed to ensure that the remuneration is:

utilized for primary care or mental health services;

limited in both amount (50% of comp, signing bonus and benefits paid to NPP, which must be FMV) and duration (not to exceed first 2 years of NPP hire).

Physician/PO and NPP must have compensation arrangement (can be employment or contract).

Remuneration must be for bona fide recruits (NPP from outside geographic area and not employed by employer).

Exception may only be used by hospital, FQHC or RHC once every 3 years for same referring physician.

Слайд 37The New Exceptions – Time-Share Arrangements

Exception for time-share arrangements involving physician

use of another’s premises, equipment, personnel, items, supplies, and/or services.

Allows use on a limited or as-needed basis. Need not comply with pre-existing Stark exceptions for office space and/or equipment leases (i.e. space, equipment need not be used exclusively during use period). Elements include:

arrangement is between (i) physician and (ii) hospital or physician organization (the physician cannot be an owner, employee or contractor of the PO);

arrangement must be set out in writing, signed by the parties, and must specify the premises, equipment, personnel, items, supplies, and services covered by the arrangement;

Allows use on a limited or as-needed basis. Need not comply with pre-existing Stark exceptions for office space and/or equipment leases (i.e. space, equipment need not be used exclusively during use period). Elements include:

arrangement is between (i) physician and (ii) hospital or physician organization (the physician cannot be an owner, employee or contractor of the PO);

arrangement must be set out in writing, signed by the parties, and must specify the premises, equipment, personnel, items, supplies, and services covered by the arrangement;

Слайд 38The New Exceptions – Time-Share Arrangements

(cont’d)

applicable premises, equipment, etc. must be

used predominantly to provide E&M services to patients and on the same schedule;

applicable equipment must be located in the same building where E&M services are furnished, and cannot include advanced imaging, radiation therapy, or clinical or pathology equipment (except for CLIA-waived tests);

arrangement can’t be conditioned on referrals;

comp must be set in advance, FMV, and not determined in manner that takes into account V or V of referrals or other business between the parties, OR using a formula based on (i) percent of revenue attributable to the services provided, or (ii) per-unit of service fees that are not time-based if reflecting services provided to patients referred by grantor to grantee of the time-share;

arrangement can’t convey a leasehold interest.

applicable equipment must be located in the same building where E&M services are furnished, and cannot include advanced imaging, radiation therapy, or clinical or pathology equipment (except for CLIA-waived tests);

arrangement can’t be conditioned on referrals;

comp must be set in advance, FMV, and not determined in manner that takes into account V or V of referrals or other business between the parties, OR using a formula based on (i) percent of revenue attributable to the services provided, or (ii) per-unit of service fees that are not time-based if reflecting services provided to patients referred by grantor to grantee of the time-share;

arrangement can’t convey a leasehold interest.

Слайд 39Modifications – Holdovers

Final Rule modifies current Stark “holdover” language in several

Stark exceptions.

Current language permits parties to compliant arrangements of at least one year to continue the arrangements for six months following expiration, without violating Stark—if the terms and conditions of the arrangement are not changed.

The modification in the Final Rule allows holdovers to continue for an indefinite period, PROVIDED the underlying arrangements continue to satisfy an applicable Stark exception for the duration of the holdover period.

Current language permits parties to compliant arrangements of at least one year to continue the arrangements for six months following expiration, without violating Stark—if the terms and conditions of the arrangement are not changed.

The modification in the Final Rule allows holdovers to continue for an indefinite period, PROVIDED the underlying arrangements continue to satisfy an applicable Stark exception for the duration of the holdover period.

Слайд 40Modifications – Signatures

Final Rule extends time-frame to obtain signatures to an

arrangement for “advertent” failures.

Under pre-existing rule,

if failure to obtain required signatures was “advertent”, parties required to obtain signatures within 30 days following effective date of the arrangement;

if failure to obtain signatures was inadvertent, “grace” period was 90 days.

Under Final Rule, 90 days to comply with signature requirement, whether failure to obtain signature earlier was “advertent” or “inadvertent”.

Under pre-existing rule,

if failure to obtain required signatures was “advertent”, parties required to obtain signatures within 30 days following effective date of the arrangement;

if failure to obtain signatures was inadvertent, “grace” period was 90 days.

Under Final Rule, 90 days to comply with signature requirement, whether failure to obtain signature earlier was “advertent” or “inadvertent”.

Слайд 41Modifications – Signatures

(cont’d)

NOTE: to utilize the grace period, all other elements

of a relevant Stark exception must be satisfied by the time the arrangement takes effect, including the requirement that the underlying arrangement be in writing at the time the arrangement takes effect.

An entity may only make use of the grace period with respect to the same referring physician once every three years.

An entity may only make use of the grace period with respect to the same referring physician once every three years.

Слайд 42Clarifications

Among the more significant “products” of the Final Rule (and the

lead-up to the Rule) are statements made by CMS which “clarify” CMS’ pre-existing interpretation of certain terms.

“In Writing”.

The requirement that arrangements must be “in writing” to satisfy a Stark exception, does NOT mean that the arrangement must be memorialized in a written contract. The “in writing” requirement can be satisfied by a collection of documents that reflect a course of conduct between the parties (i.e., agreement to the arrangement before referrals began).

“In Writing”.

The requirement that arrangements must be “in writing” to satisfy a Stark exception, does NOT mean that the arrangement must be memorialized in a written contract. The “in writing” requirement can be satisfied by a collection of documents that reflect a course of conduct between the parties (i.e., agreement to the arrangement before referrals began).

Слайд 43Clarifications –

“At Least One Year”.

The requirement that arrangements have a term

of at least one year does NOT mean that a written agreement must be in place that includes an explicit provision containing a one-year (or greater) term.

An arrangement can satisfy the one-year requirement if the parties can demonstrate that it in fact lasted for one year or, if terminated during the first year, the parties did not enter into a new arrangement for the same space, equipment or services during the first year.

An arrangement can satisfy the one-year requirement if the parties can demonstrate that it in fact lasted for one year or, if terminated during the first year, the parties did not enter into a new arrangement for the same space, equipment or services during the first year.