Walkable Streets

@danielequercia @rschifan @lajello @walkonomics

- Главная

- Разное

- Дизайн

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Аналитика

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Красота и здоровье

- Финансы

- Государство

- Путешествия

- Спорт

- Недвижимость

- Армия

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

The Digital Life of Walkable Streets презентация

Содержание

- 1. The Digital Life of Walkable Streets

- 2. We cannot afford to leave architecture to architects

- 3. We cannot afford to leave computers to engineers

- 4. Neil Gershenfeld Director of MIT’s Center

- 6. U C L

- 7. U C L daniele quercia

- 8. U C L

- 9. U C L

- 10. U C L

- 11. U C L

- 14. offline & online

- 17. Jane Jacob Kevin Lynch

- 18. Quiet Happy Beauty Google for “Happy Maps”

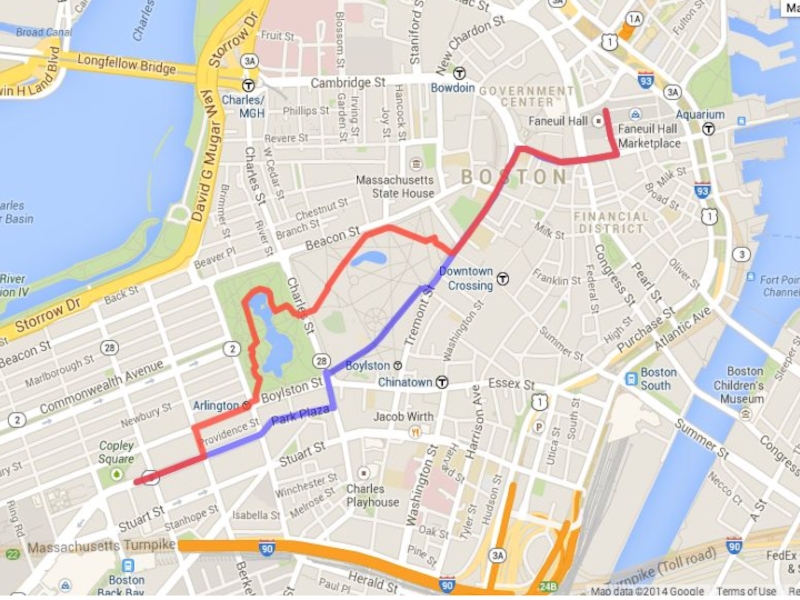

- 19. The shortest Path to Happiness

- 20. Walkability

- 21. Why Walkability? Adds 5-10 % to

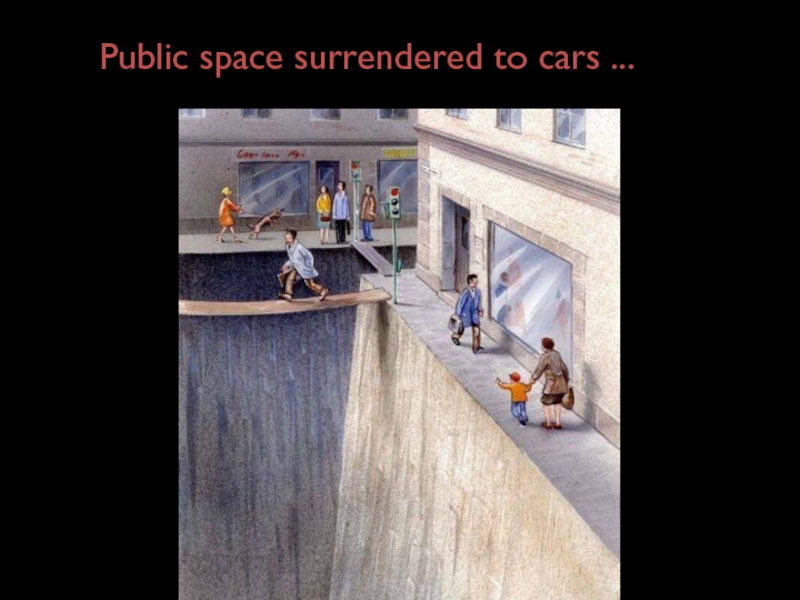

- 22. Public space surrendered to cars ...

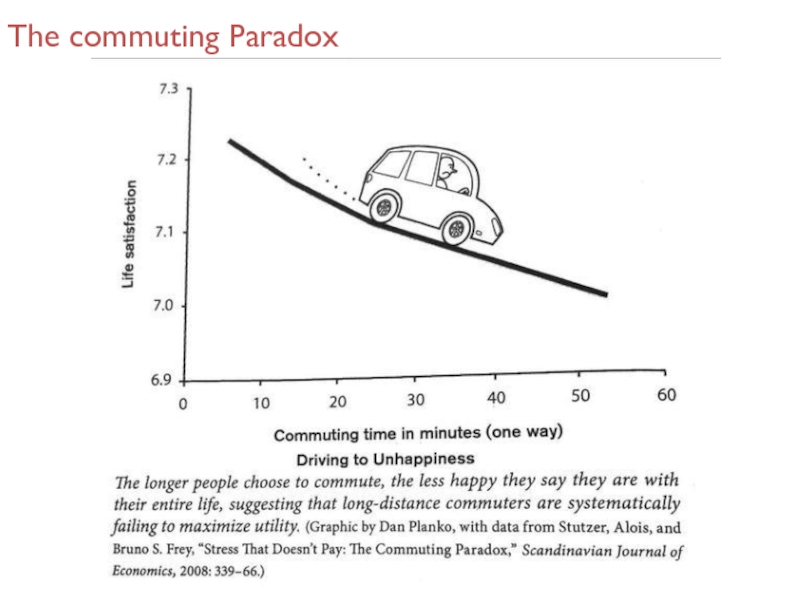

- 23. The commuting Paradox

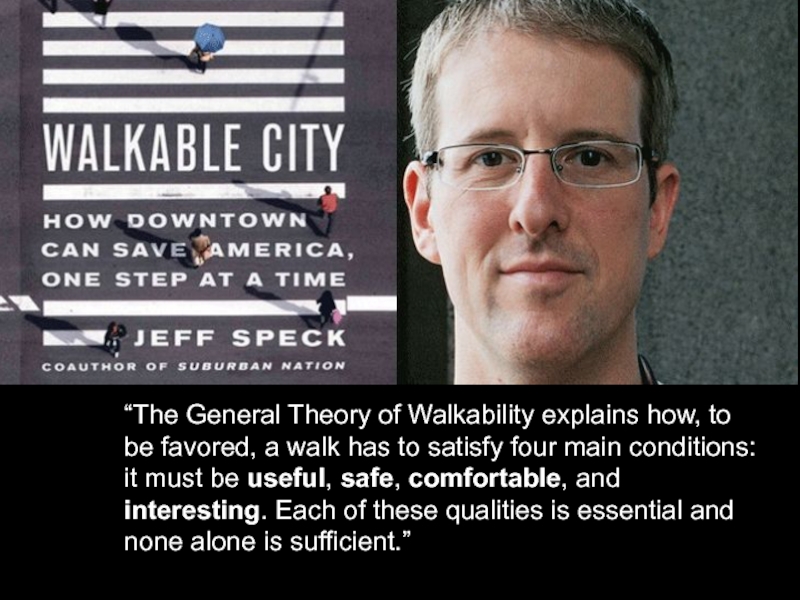

- 24. “The General Theory of Walkability explains how,

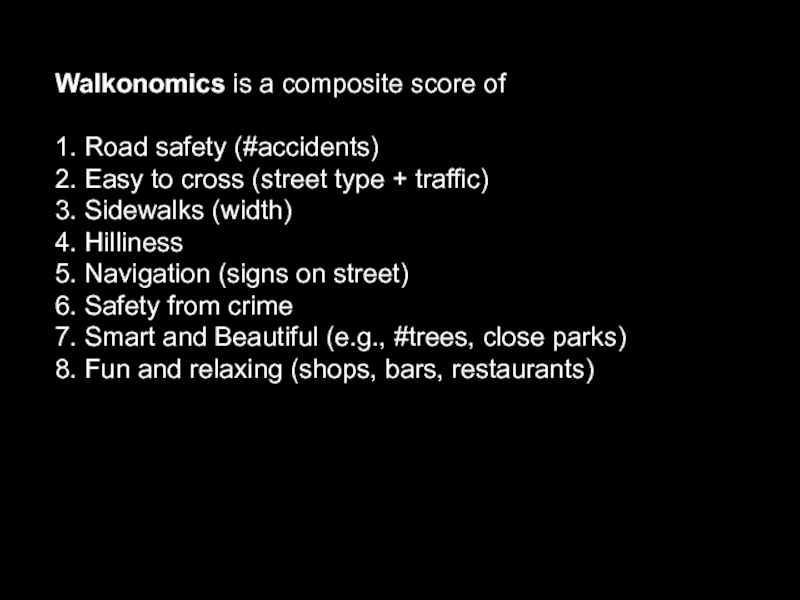

- 26. Walkonomics is a composite score of

- 29. Hypothesis A street’s vitality is captured in

- 30. Method 1. Theoretically derive hypotheses concerning

- 31. Reliability Measurement error borrow measurement

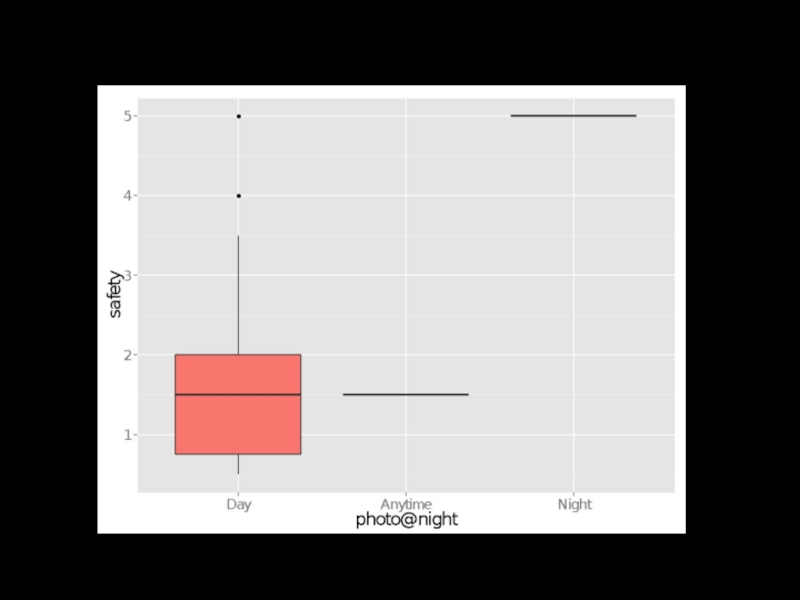

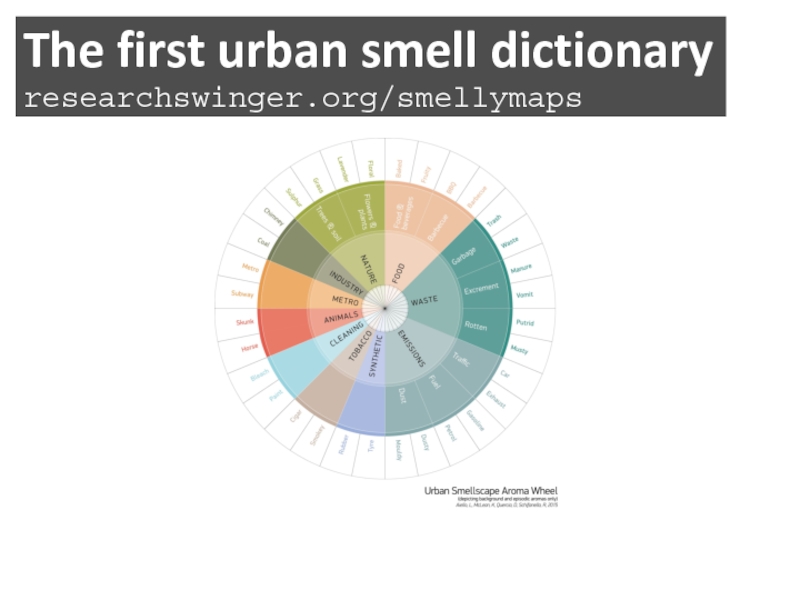

- 32. Time of Day

- 33. Jane Jacobs

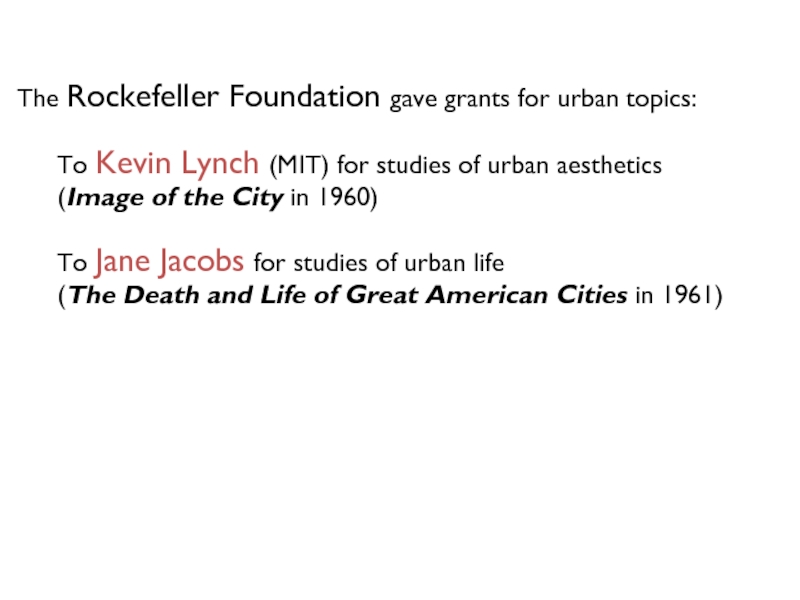

- 34. The Rockefeller Foundation gave grants for urban

- 35. The Death and Life of Great American

- 36. Death caused by elimination of pedestrian activity

- 37. nothing is safer than a city street

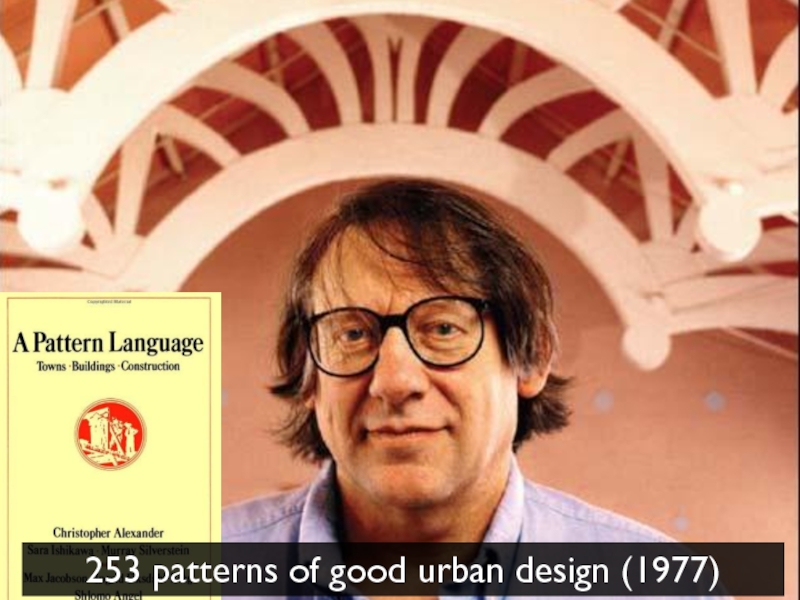

- 38. 253 patterns of good urban design (1977)

- 39. “At night, street crimes are most

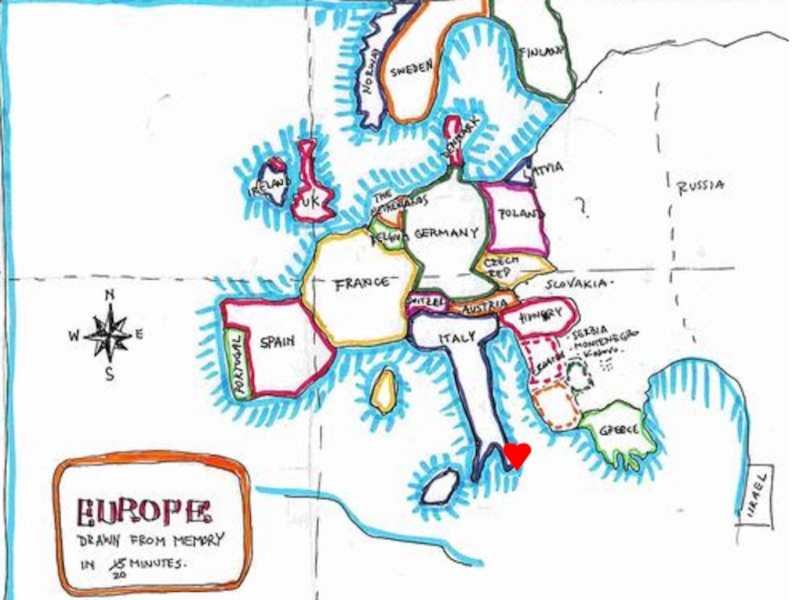

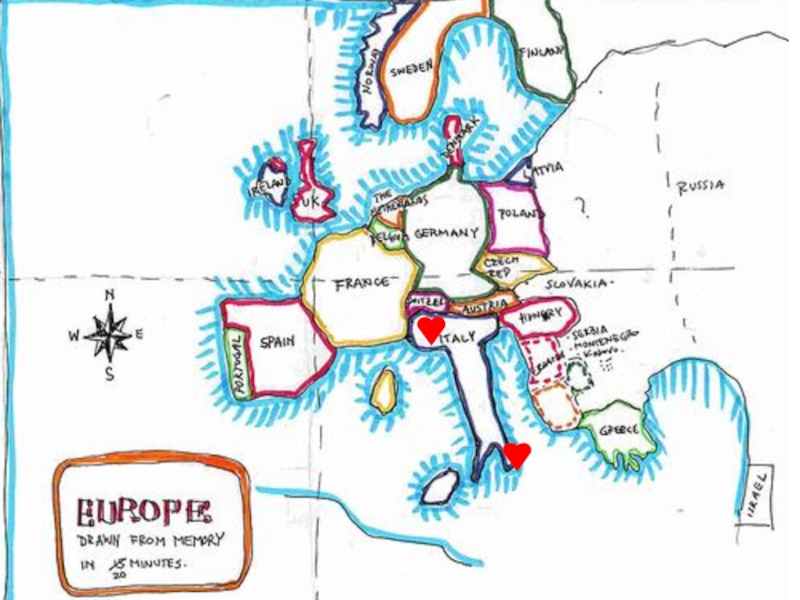

- 40. Question 1 Can safe streets be identified by night activity?

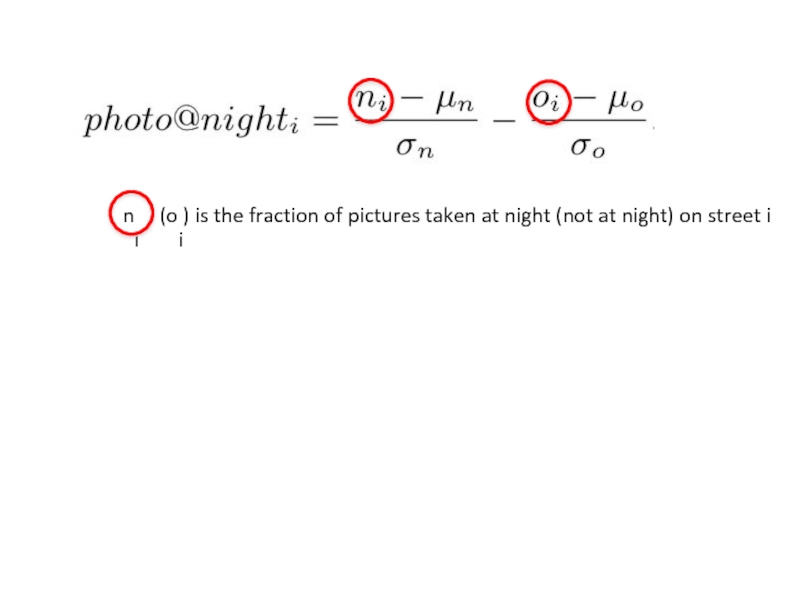

- 41. ni (oi) is the fraction

- 42. r(safe,night)= 0.60 safe street tend to be visited at night as well

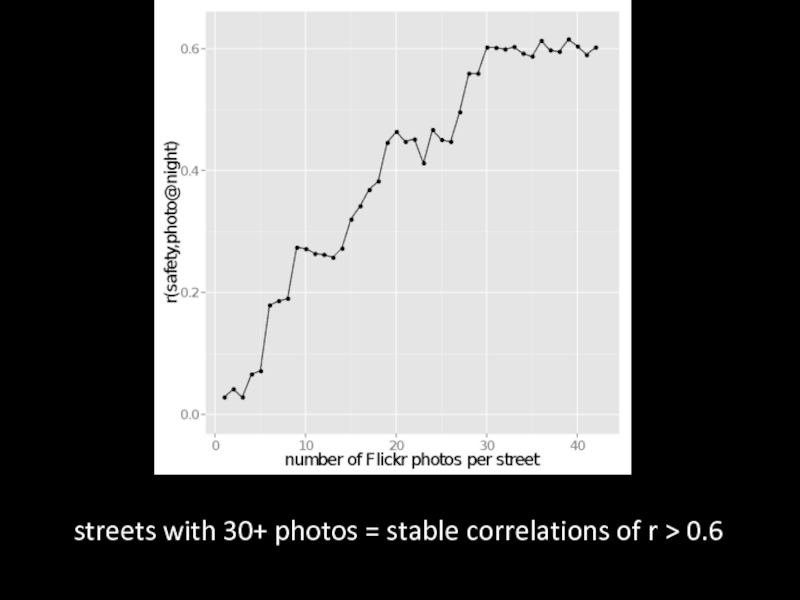

- 44. streets with 30+ photos = stable correlations of r > 0.6

- 45. What about making “it worth a thief’s

- 46. Question 2 Can safe streets be identified by gender or age?

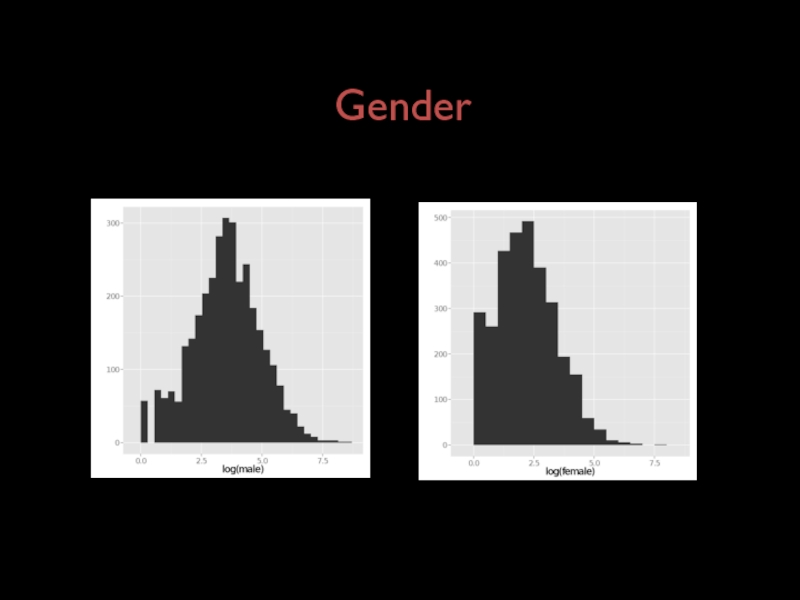

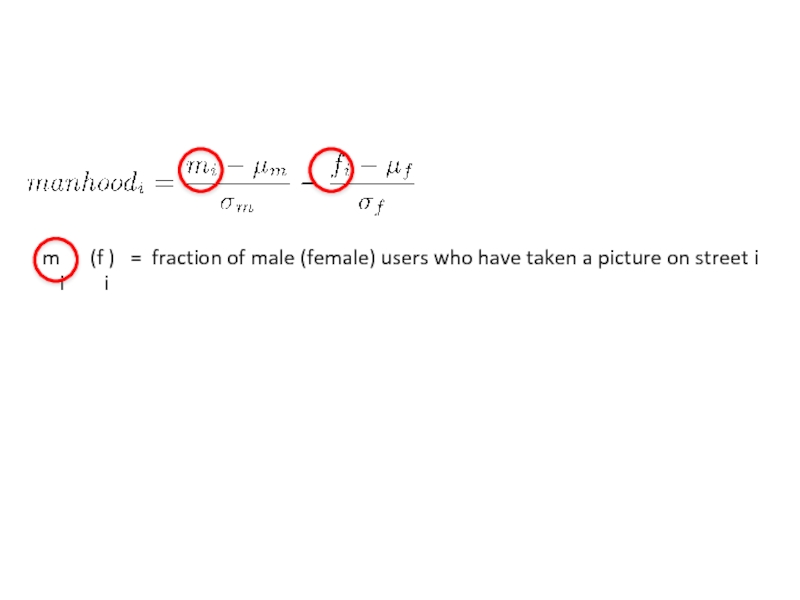

- 47. Gender

- 48. mi (fi) = fraction

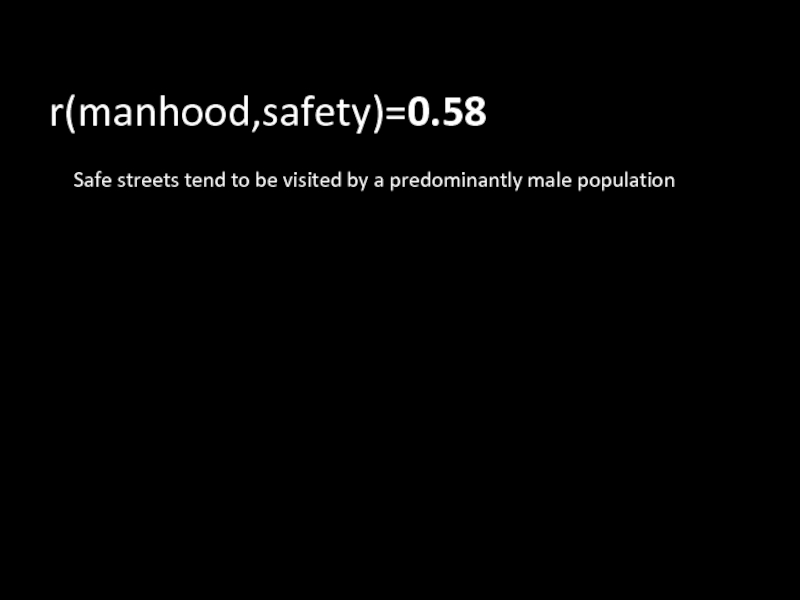

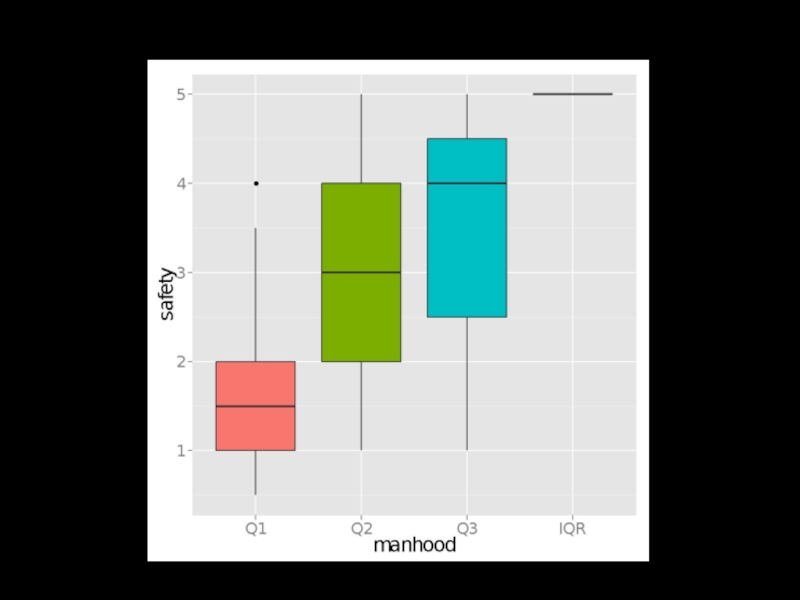

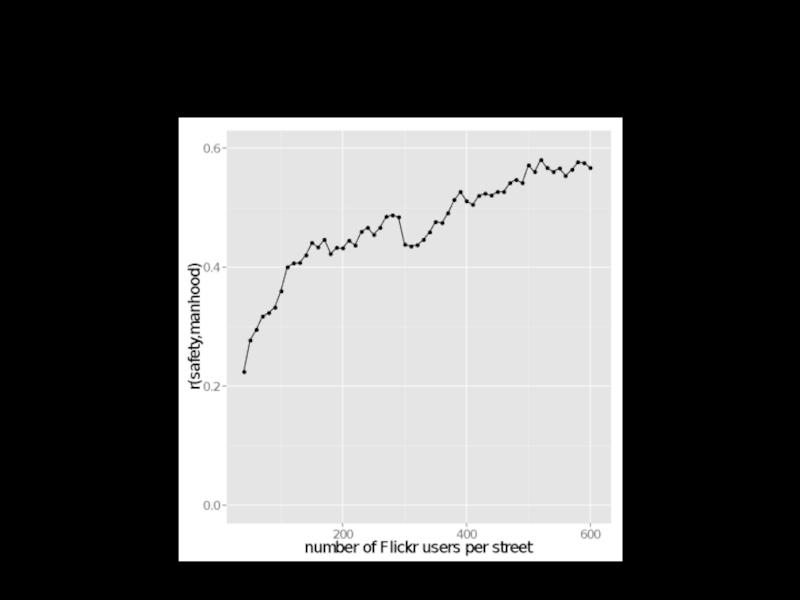

- 49. r(manhood,safety)=0.58 Safe streets tend to be visited by a predominantly male population

- 52. Age

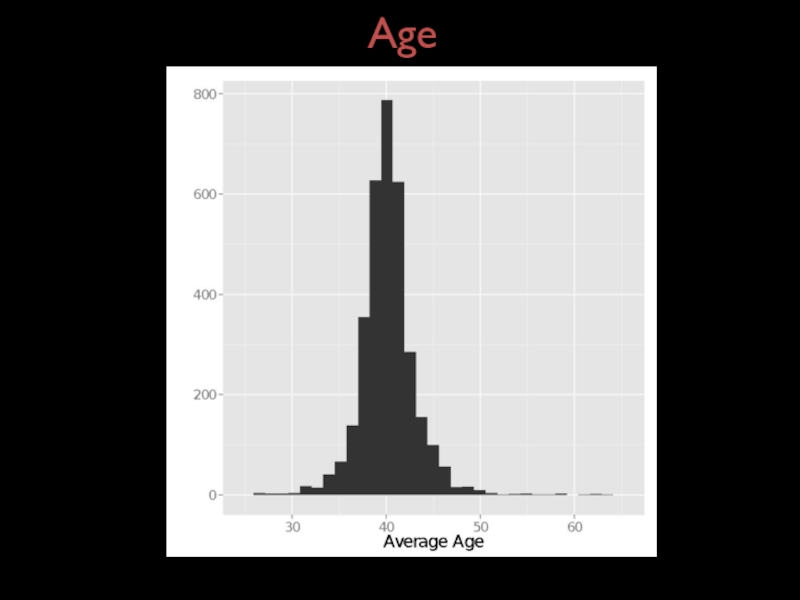

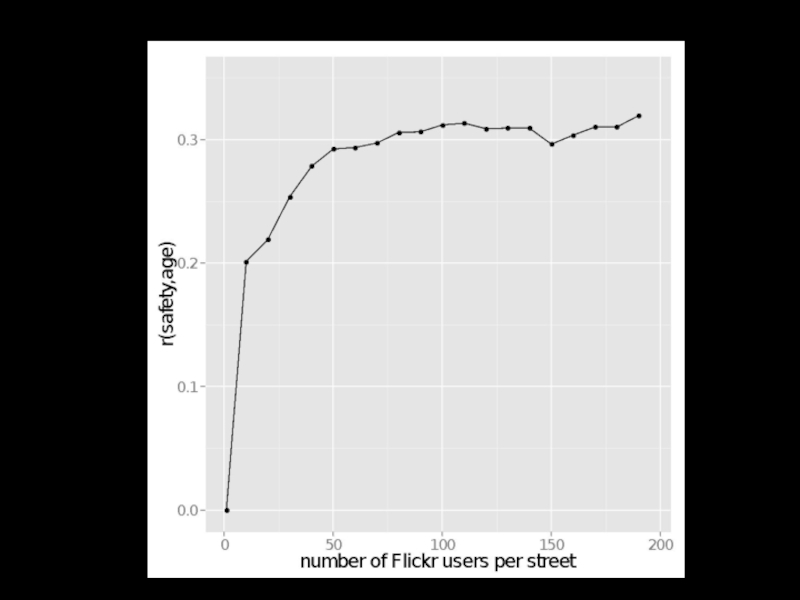

- 53. r(age,safety)=0.32 unsafe streets tend to be visited by a younger population

- 55. Crime prevention through environmental design

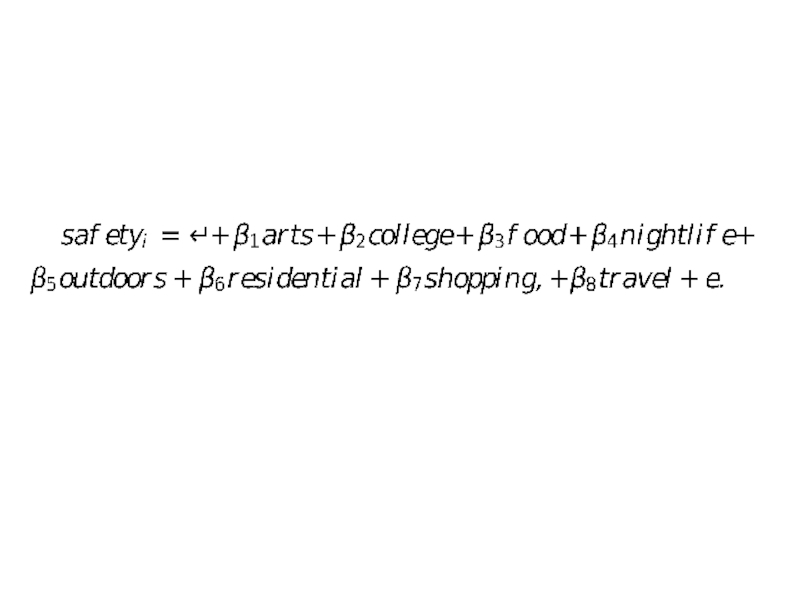

- 56. Questions 3 & 4 Can safe (walkable)

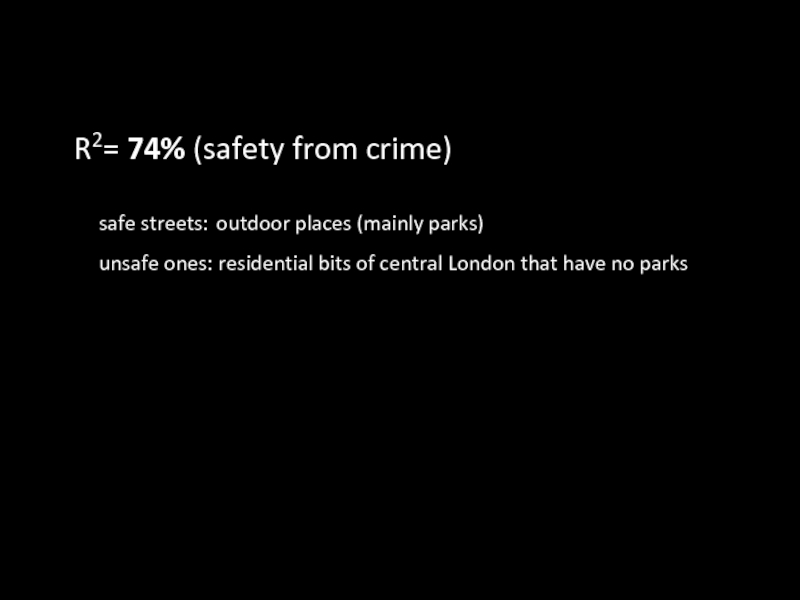

- 58. R2= 74% (safety from crime) safe

- 59. R2= 33% (walkability) the presence of

- 60. Text we gather the literature on walkability

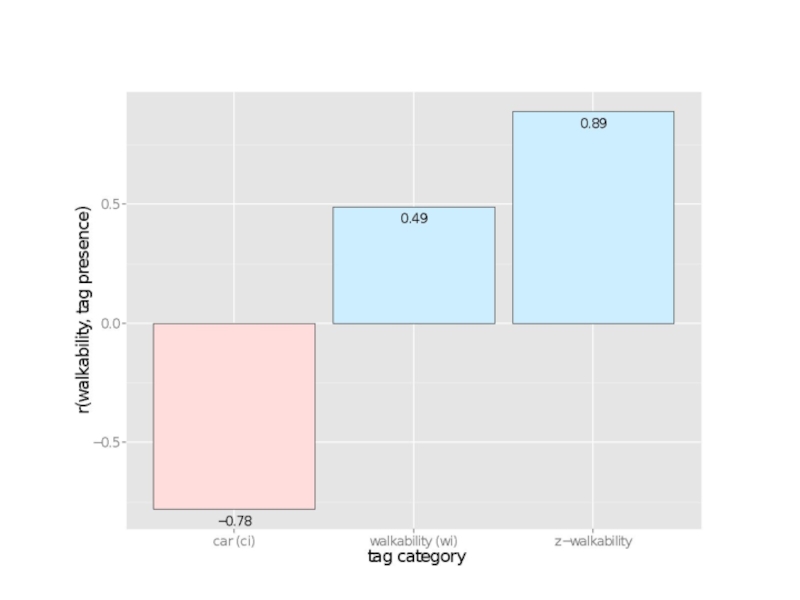

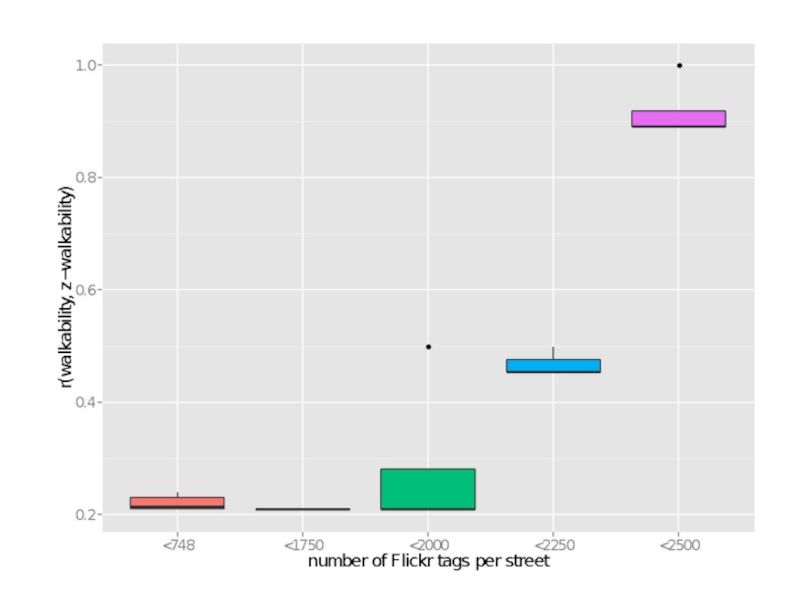

- 61. Question 5 Can walkable streets be identified by walkability-related tags?

- 64. To sum up... Picture uploads from

- 65. Theoretical Implication Social media = Opportunities

- 66. Practical Implications Room booking Urban route recommendations Real-estate

- 67. Limitation It doesn’t work where there is little activity (yet absence/presence of venues work)

- 68. Happy Maps The Digital Life of Walkable Streets

- 69. Smelly Maps The Digital Life of Urban Smellscapes

- 70. Humans Can Discriminate More than 1 Trillion Olfactory Stimuli Science, March 2014

- 71. Yet, city planning can discriminate only a few bad odors

- 72. nasal ranger

- 73. smell walks Amsterdam, Pamplona, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newport, Paris, New York.

- 74. Good classification The first urban smell dictionary researchswinger.org/smellymaps

- 75. Happy Maps The Digital Life of Walkable Streets

- 76. Smelly Maps The Digital Life of Urban Smellscapes

- 77. Chatty Maps The Digital Life of Urban Soundscapes

- 81. The Digital Life of Walkable Streets

Слайд 4Neil Gershenfeld

Director of MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms

“Computer science

is one of the worst things to happen to computers or to science because, unlike physics, it has arbitrarily segregated the notion that computing happens in an alien world.”

Слайд 21Why Walkability?

Adds 5-10 % to house prices

@ the heart

of the cure to the health-care crisis in US

Carbon saving (light-bulbs 1 year= living in a walkable for 1 week) neighborhood in 1 week)

Carbon saving (light-bulbs 1 year= living in a walkable for 1 week) neighborhood in 1 week)

Слайд 24“The General Theory of Walkability explains how, to be favored, a

walk has to satisfy four main conditions: it must be useful, safe, comfortable, and interesting. Each of these qualities is essential and none alone is sufficient.”

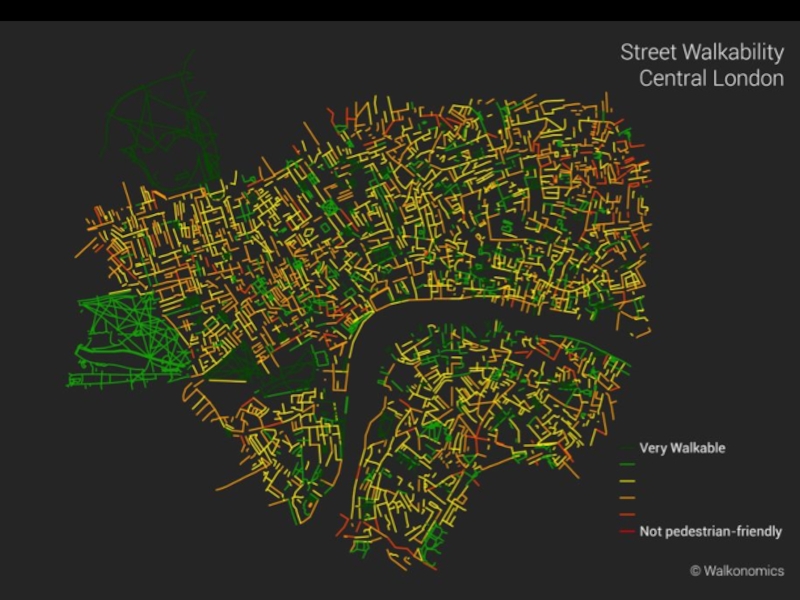

Слайд 26Walkonomics is a composite score of

1. Road safety (#accidents)

2. Easy

to cross (street type + traffic)

3. Sidewalks (width)

4. Hilliness

5. Navigation (signs on street)

6. Safety from crime

7. Smart and Beautiful (e.g., #trees, close parks)

8. Fun and relaxing (shops, bars, restaurants)

3. Sidewalks (width)

4. Hilliness

5. Navigation (signs on street)

6. Safety from crime

7. Smart and Beautiful (e.g., #trees, close parks)

8. Fun and relaxing (shops, bars, restaurants)

Слайд 29Hypothesis

A street’s vitality is captured in the digital layer

(there might be

digital footprints that distinguish walkable streets from unwalkable ones)

Слайд 30Method

1. Theoretically derive hypotheses concerning walkability

2. Test them

3. If supported, then

“valid” scores

Слайд 31Reliability

Measurement error

borrow measurement procedures from the literature

(e.g., a buffer

of 22.5 meters around each street’s polyline)

Specification error (Flickr/Foursquare biases) normalization measures (e.g., z-transformations) from previous studies

Sampling error

minimum amount of data such that the same results on repeated trials

Specification error (Flickr/Foursquare biases) normalization measures (e.g., z-transformations) from previous studies

Sampling error

minimum amount of data such that the same results on repeated trials

Слайд 34The Rockefeller Foundation gave grants for urban topics:

To Kevin Lynch

(MIT) for studies of urban aesthetics

(Image of the City in 1960)

To Jane Jacobs for studies of urban life

(The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961)

(Image of the City in 1960)

To Jane Jacobs for studies of urban life

(The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961)

Слайд 35The Death and Life of Great American Cities

the most influential

book in city planning

(“social capital", "mixed primary uses", "eyes on the street”)

critique of the 1950s urban renewal policies

(attacking Moses for “replacing well-functioning neighborhoods

with Le Corbusier-inspired towers”)

(“social capital", "mixed primary uses", "eyes on the street”)

critique of the 1950s urban renewal policies

(attacking Moses for “replacing well-functioning neighborhoods

with Le Corbusier-inspired towers”)

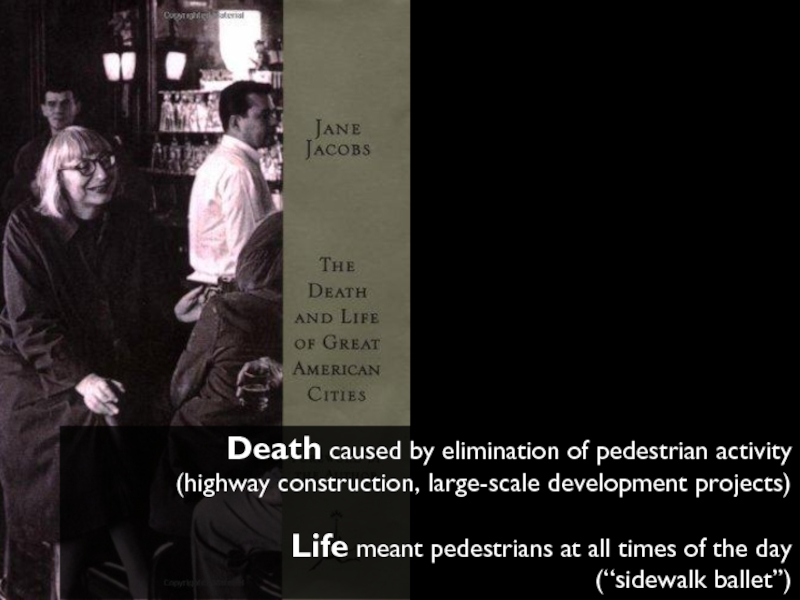

Слайд 36Death caused by elimination of pedestrian activity

(highway construction, large-scale development projects)

Life meant pedestrians at all times of the day

(“sidewalk ballet”)

Life meant pedestrians at all times of the day

(“sidewalk ballet”)

Слайд 39

“At night, street crimes are most prevalent in places where there

are too few pedestrians to provide natural surveillance, but enough pedestrians to make it worth a thief’s while”

Слайд 45What about making “it worth a thief’s while”?

unsafe

ones are used by men only

OR unsafe streets used by women

OR unsafe streets used by women

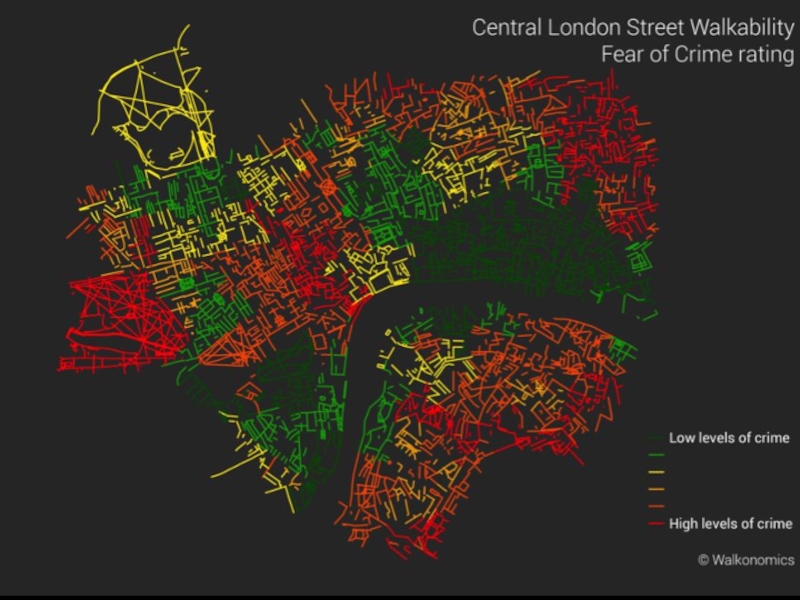

Слайд 55Crime prevention through environmental design

The physical environment can be

designed or

manipulated to reduce fear of crime (by

supporting certain activities over others)

manipulated to reduce fear of crime (by

supporting certain activities over others)

Слайд 56Questions 3 & 4

Can safe (walkable) streets be identified by the

presence of specific types of places?

Слайд 58R2= 74% (safety from crime)

safe streets: outdoor places (mainly parks)

unsafe ones: residential bits of central London that have no parks

Слайд 59R2= 33% (walkability)

the presence of residential areas drives most of

the predictive power of the regression

Слайд 60Text

we gather the literature on walkability to produce a list of

walkability-related keywords

Line-by-line coding

Collecting documents

Annotating them

Validating them

Line-by-line coding

Collecting documents

Annotating them

Validating them

Слайд 64To sum up...

Picture uploads from dwellers of walkable streets differ from

those of unwalkable ones, mainly in terms of upload time and tagging *

* limited data vs. high penetration

Слайд 65Theoretical Implication

Social media = Opportunities for Theory

Comforted by our validation

work, urban researchers might well be enticed to use social media to answer theoretical questions that could not have been tackled before because of lack of data

Слайд 67Limitation

It doesn’t work where there is little activity

(yet absence/presence of venues

work)

Слайд 81

The Digital Life of Walkable Streets

The Digital Life of

Walkable Streets

@danielequercia @rschifan @lajello @walkonomics

@danielequercia @rschifan @lajello @walkonomics