- Главная

- Разное

- Дизайн

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Аналитика

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Красота и здоровье

- Финансы

- Государство

- Путешествия

- Спорт

- Недвижимость

- Армия

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

The social self презентация

Содержание

- 1. The social self

- 2. “NO TOPIC IS MORE INTERESTING TO PEOPLE

- 3. What is the “self”? In psychology: collection

- 4. What is the “self”? Most recently, “self”

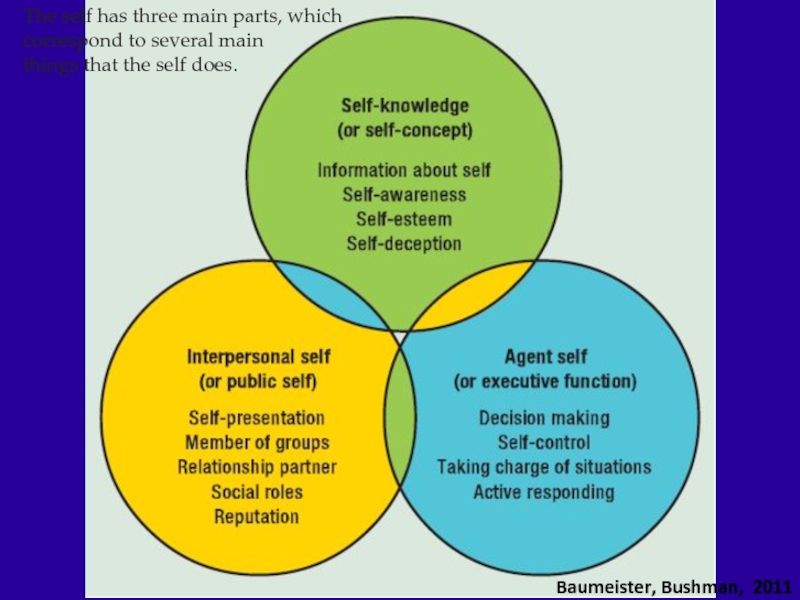

- 5. Baumeister, Bushman, 2011 The self has

- 6. Self-concept Human beings have self-awareness, and this

- 7. Interpersonal self A second part of the

- 8. Agent Self The third important part of

- 9. Self-concept Self-awareness Self-esteem Self-deception Self-efficacy

- 10. Self-awareness Attention directed to the self

- 11. Self-awareness Early in the 1970s social

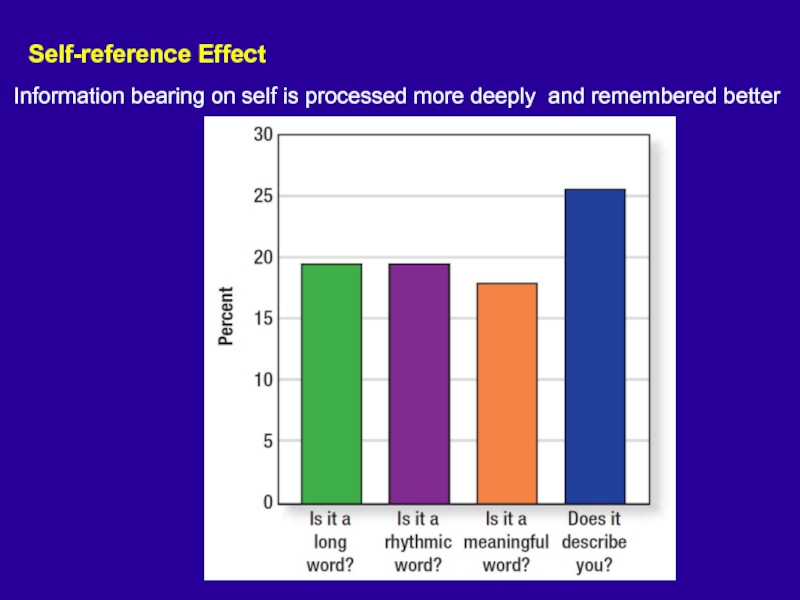

- 12. Self-reference Effect

- 13. Social Comparison Theory Festinger suggested that people

- 16. Social Comparison Theory Festinger suggested that people

- 19. self-affirmation theory People seek new

- 20. Self-Evaluation Maintenance Model In order to maintain

- 21. Self-deception strategies Self Serving Bias (mentioned in

- 22. Self-awareness Private self-awareness refers to attending

- 23. Self-Monitoring Self-monitoring is the degree to which

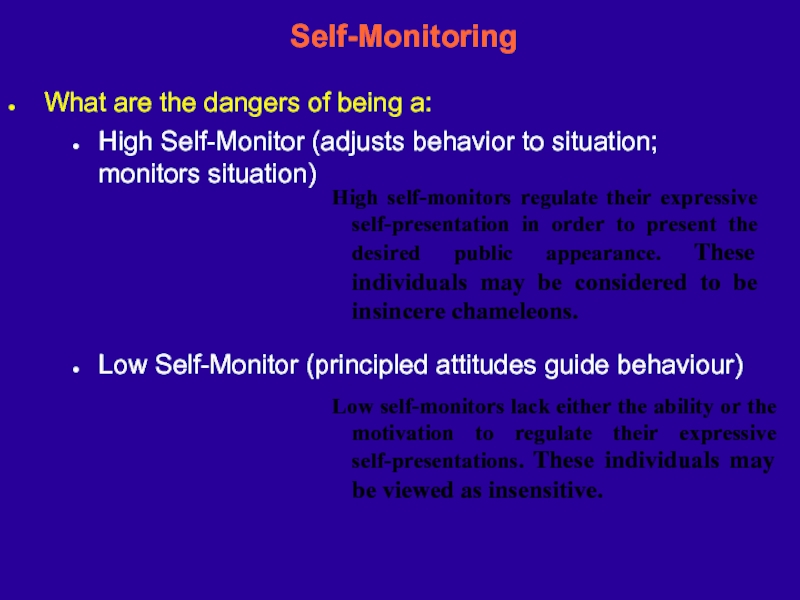

- 24. Self-Monitoring What are the dangers

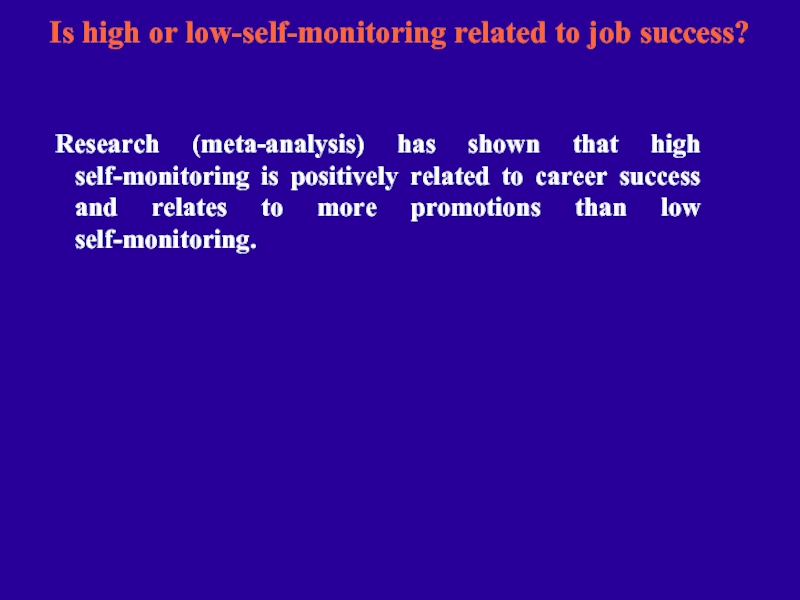

- 25. Is high or low-self-monitoring related to job

- 26. Benefits of high self-esteem Feels good Helps

- 27. Self-esteem Self-esteem reflects a person's overall subjective

- 28. Benefits of high self-esteem Feels good Helps

- 29. Benefits of high self-esteem Feels good Helps

- 30. Self-esteem Self-esteem serves as a sociometer

- 31. Why do we care about self-esteem? Self-esteem

- 32. Why do we care about self-esteem? Self-esteem

- 33. A

- 34. Negative aspects of highest self-esteem Narcissism Subset

- 35. Self-efficacy Belief in one’s capacity to succeed

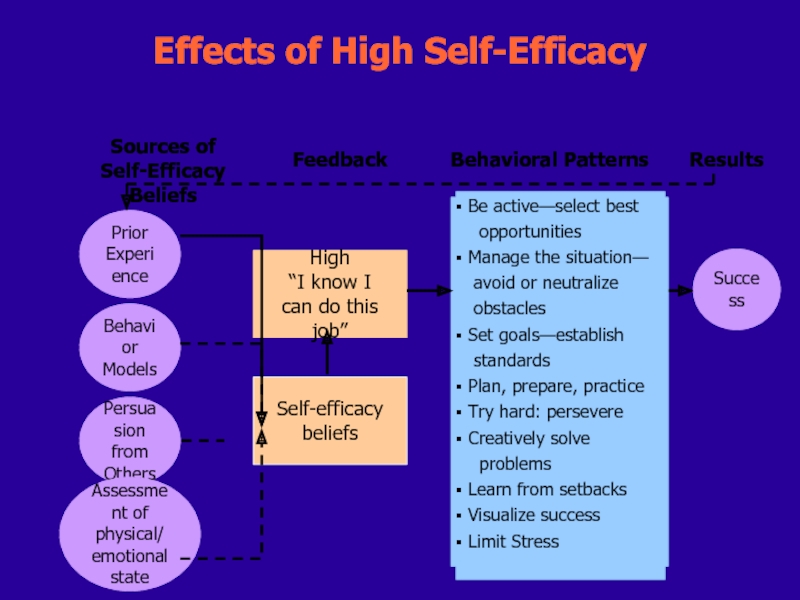

- 36. Effects of High Self-Efficacy Prior Experience

- 37. People can program themselves for success or

- 38. Effects of High Self-Efficacy Prior Experience

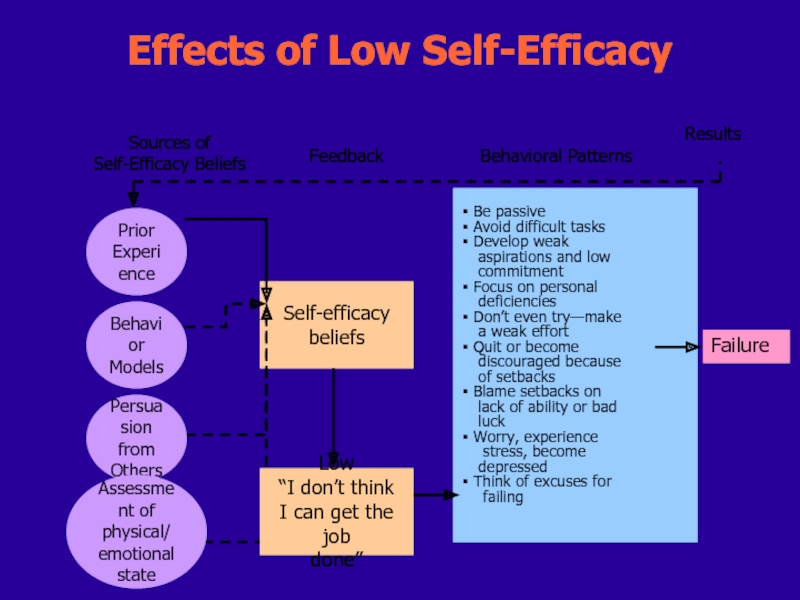

- 39. Effects of Low Self-Efficacy Sources of Self-Efficacy

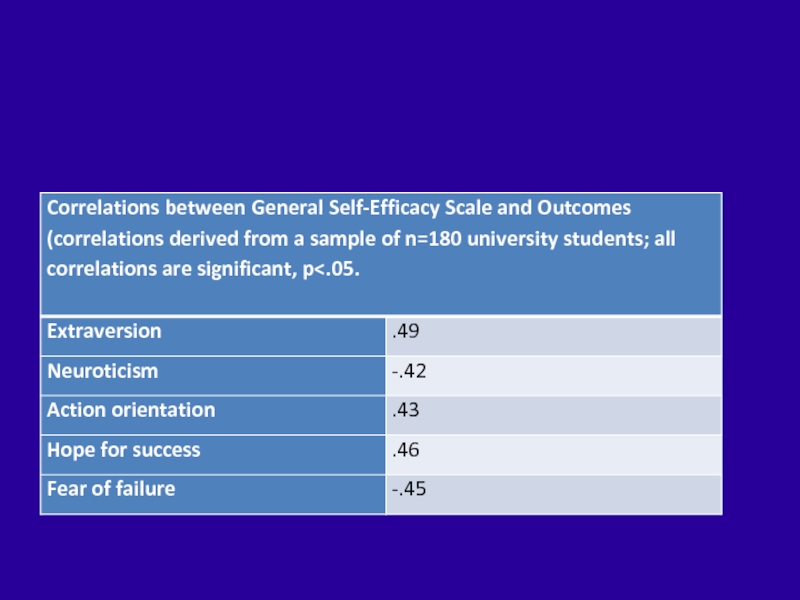

- 41. The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE)

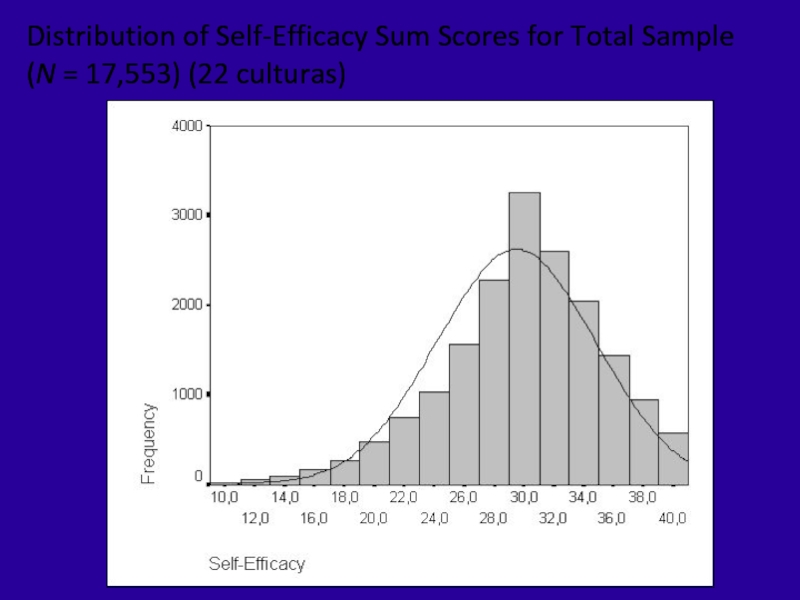

- 42. Distribution of Self-Efficacy Sum Scores for Total Sample (N = 17,553) (22 culturas)

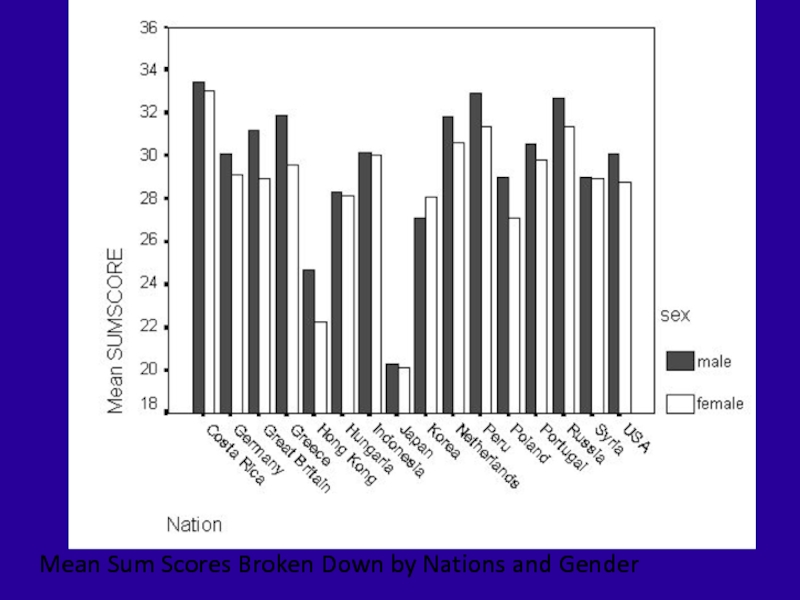

- 43. Mean Sum Scores Broken Down by Nations and Gender

- 44. Interpersonal self self – presentation

- 45. Functions of self-presentation Social acceptance Increase chance

- 46. Interpersonal Self The idea that cultural styles

- 47. self-construal Markus and Kitayama (1991) published their

- 48. self-construal They argued that Western cultures are

- 49. Interdependent of Self-Concept In individualistic cultures it

- 50. self-construal They proposed that people with

- 52. self-construal Markus and Kitayama’s (1991) proposals had

- 53. self-construal Their work may have added scientific

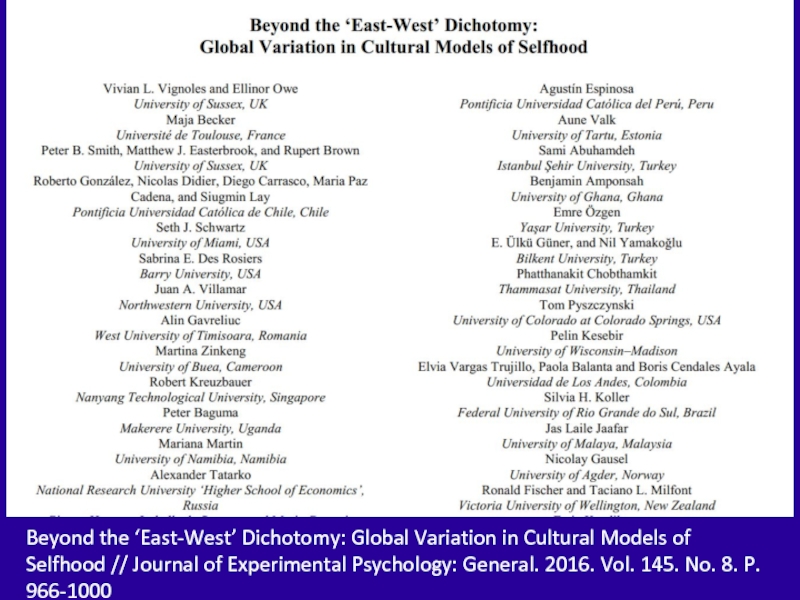

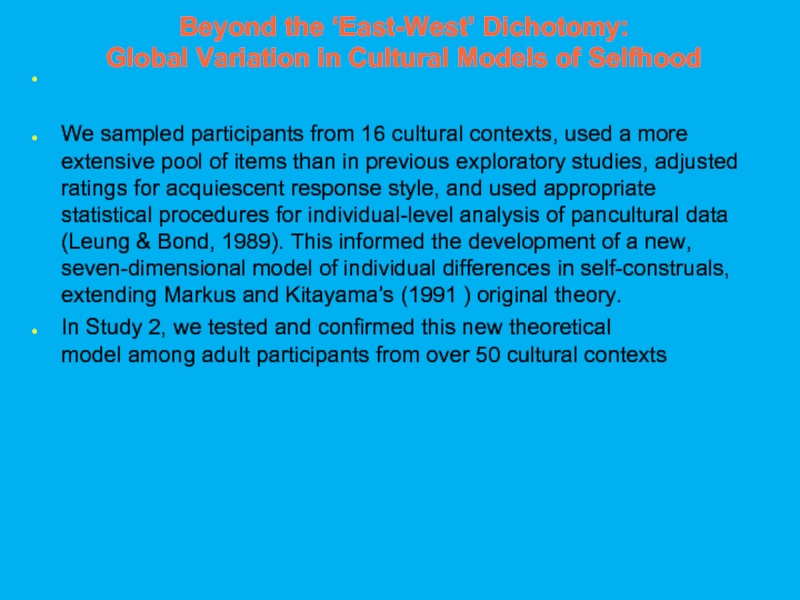

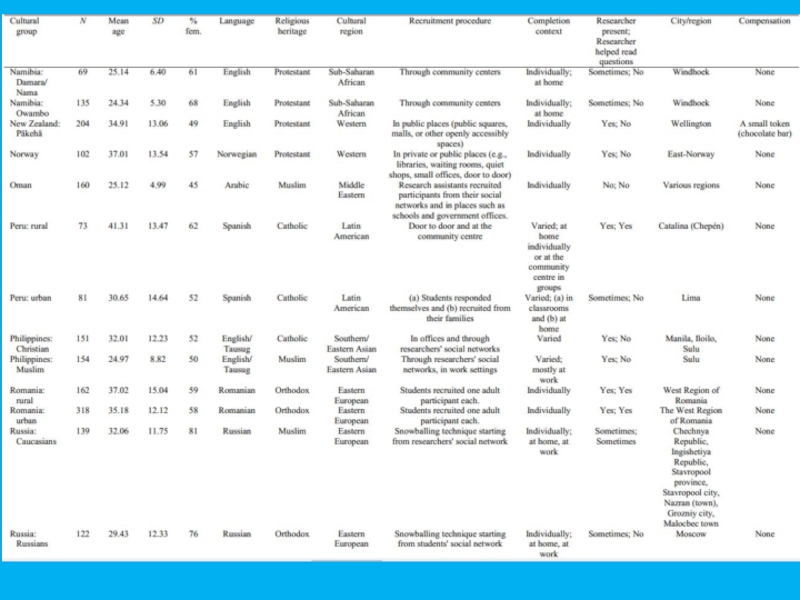

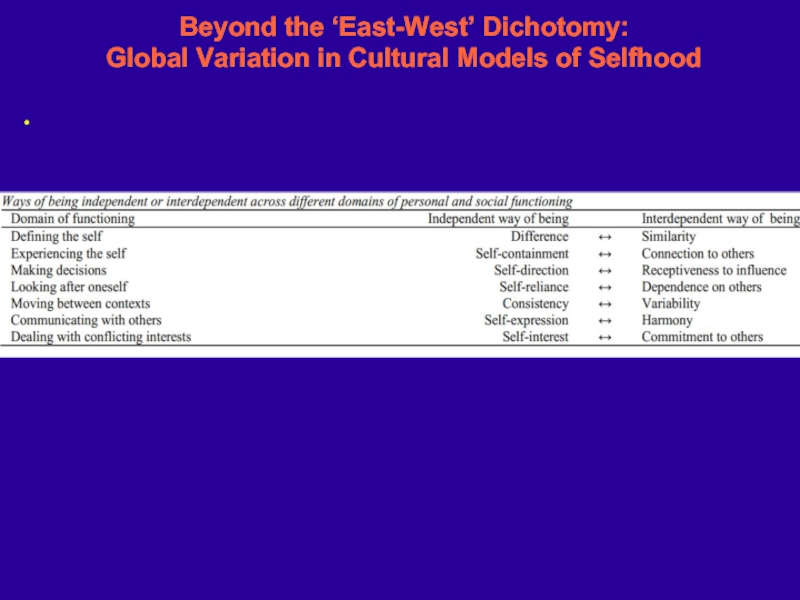

- 54. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation

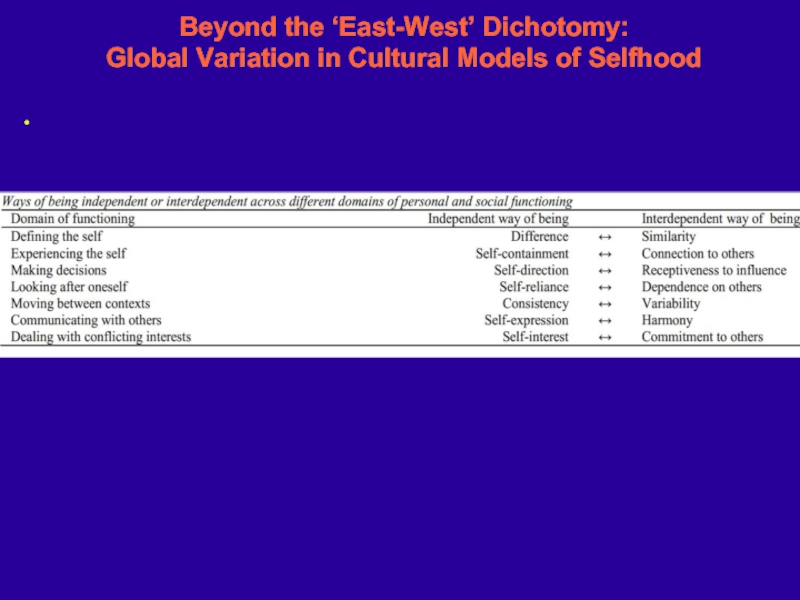

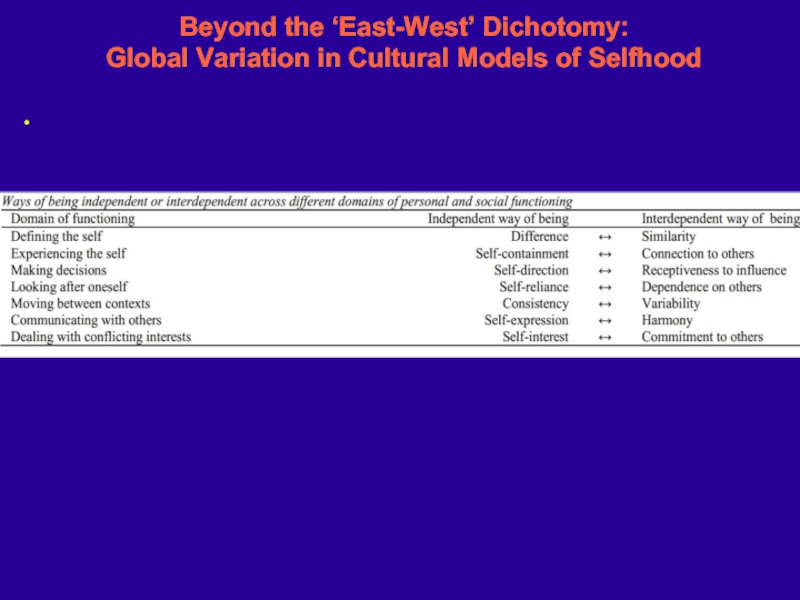

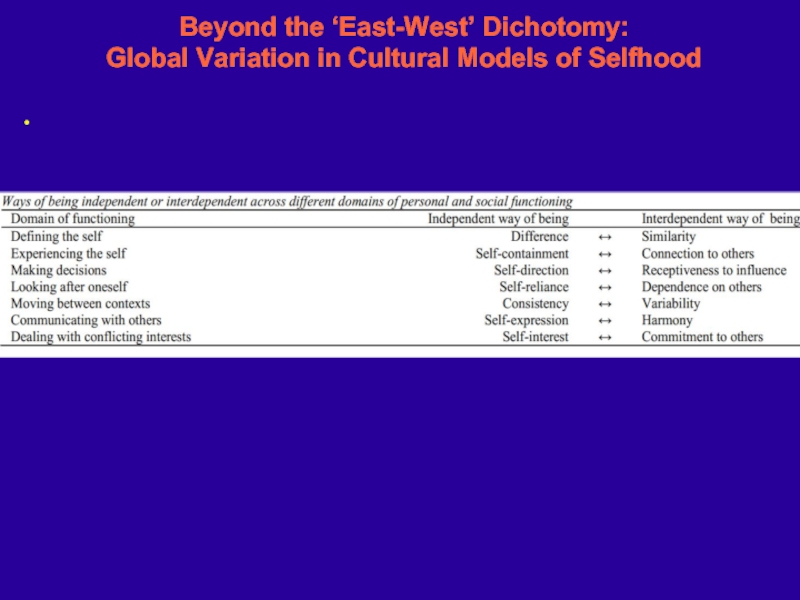

- 55. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in

- 56. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in

- 57. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in

- 58. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 59. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 60. Component I appeared to contrast a desire

- 61. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 62. Component I appeared to contrast a desire

- 63. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 64. Component I appeared to contrast a desire

- 65. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 66. Component I appeared to contrast a desire

- 67. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 68. Component I appeared to contrast a desire

- 69. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 70. Component I appeared to contrast a desire

- 71. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 72. Component I appeared to contrast a desire

- 73. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 74. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

- 75. Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in

- 76. Self-Interest

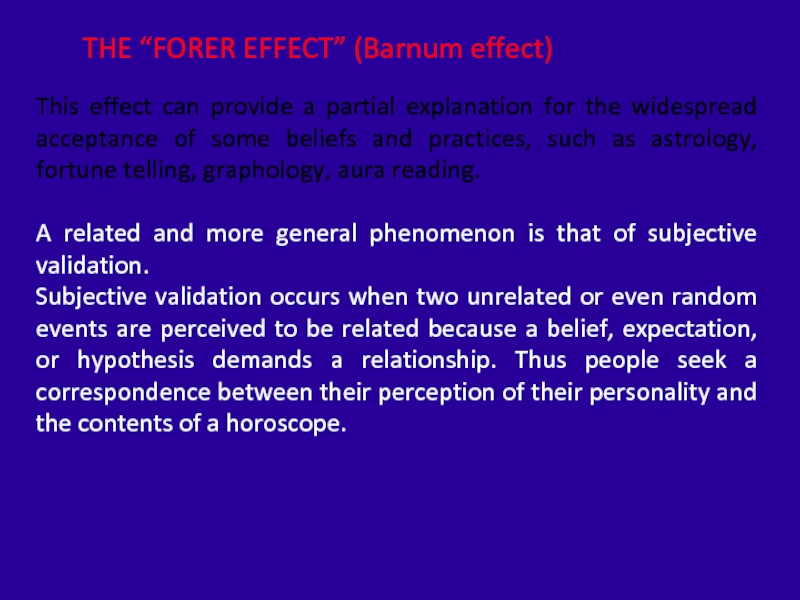

- 77. Self-interest THE “FORER EFFECT” (Barnum effect)

- 78. The Forer effect (also called the Barnum

- 79. This effect can provide a partial explanation

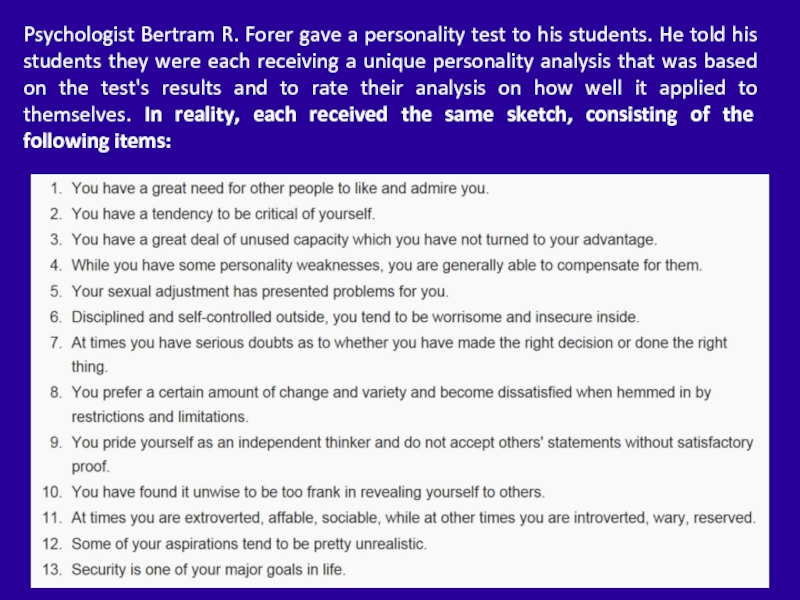

- 80. Psychologist Bertram R. Forer gave a personality

- 81. On average, the students rated its accuracy

- 82. THE “FORER EFFECT” (Barnum effect) Subjects give

- 84. This effect exists due to our self interest. Just someone who exploits our self interest.)

Слайд 2“NO TOPIC IS MORE

INTERESTING TO PEOPLE

THAN PEOPLE. FOR MOST

PEOPLE, MOREOVER, THE

MOST

THE SELF.”

—ROY F. BAUMEISTER,

THE SELF IN SOCIAL

PSYCHOLOGY, 1999

Слайд 3What is the “self”?

In psychology:

collection of cognitively-held beliefs that a person

about themselves.

However…

“Self” seems to extend beyond the physical self (body), to include psychologically meaningful personal possessions and personal space.

Many, varied theories about the purpose and function of the ‘self’ – e.g., philosophy, science, culture, religion.

Слайд 4What is the “self”?

Most recently, “self” has been further complexified and

increasingly seen as:

Dynamic & changeable

Multiple / Plural

Hierarchical

Situational & cognitively influenced

Culturally constructed

Interest in the self increased rapidly in the 1960s and 1970s.

Слайд 5 Baumeister, Bushman, 2011

The self has three main parts, which correspond

Слайд 6Self-concept

Human beings have self-awareness, and this awareness enables them to develop

If someone says “Tell me something about yourself,” you can probably furnish 15 or 20 specific answers without having to think very hard.

You check your hair in a mirror or your weight on a scale. You read your horoscope or the results of some medical tests.

Such moments show the self reflecting on itself and on its store of information about itself.

.

Слайд 7Interpersonal self

A second part of the self that helps the person

Most people have a certain image that they try to convey to others. This public self bears some resemblance to the self-concept, but the two are not the same. Often, people work hard to present a particular image others even if it is not exactly the full, precise truth as they know it.

Furthermore, many emotions indicate concern over how one appears to others: You feel embarrassed because someone saw you do something stupid, or even just because your underwear was showing.

You feel guilty if you forgot your romantic partner’s birthday. You are delighted when your boss compliments you on your good work. These episodes reveal that the self is often working in complex ways to gain social acceptance and maintain good interpersonal relationships.

.

.

Слайд 8Agent Self

The third important part of the self, the agent self,

Sometimes you decide not to eat something because it is unhealthy or fattening.

Sometimes you make a promise and later exert yourself to keep it. Sometimes you decide what courses to take or what job to take. Perhaps you cast a vote in an election. Perhaps you sign a lease for an apartment. Perhaps you place a bet on a sports event.

All these actions reveal the self as not just a knower but also as a doer. .

Слайд 10Self-awareness

Attention directed to the self

Usually involves evaluative comparison.

In general, people

about themselves (but a lot of time is spent thinking

about self-presentation and self-preservation)

Certain situations

(e.g., mirrors, cameras, audiences, self-development exercises)

Слайд 11Self-awareness

Early in the 1970s social psychologists began studying the difference

They developed several clever procedures to increase self-awareness, such as having people work while seated in front of a mirror, or telling people that they were being videotaped.

Слайд 12 Self-reference Effect

Information bearing on self is

Слайд 13Social Comparison Theory

Festinger suggested that people compare themselves to others because,

Слайд 16Social Comparison Theory

Festinger suggested that people compare themselves to others because,

- Desire to see self-positively appears more powerful that desire to see self-accurately

In-group comparisons “my salary is pretty good for a woman.”

Suls, J. E., & Wills, T. A. E. (1991). Social comparison: Contemporary theory and research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Слайд 19

self-affirmation theory

People seek new favourable knowledge about themselves as well as

People are guided by a self-enhancement motive (e.g. Kunda, 1990).

One manifestation of this motive is described by self-affirmation theory (Sherman & Cohen, 2006).

People strive publicly to affirm positive aspects of who they are.

The urge to self-affirm is particularly strong when an aspect of one's self-esteem has been damaged.

So, for example, if someone draws attention to the fact that you are a lousy artist, you might retort that while that might be true, you are an excellent dancer.

Слайд 20Self-Evaluation Maintenance Model

In order to maintain a positive view of the

Tesser, A. (1988). Toward a self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior. Advances in experimental social psychology, 21, 181-227.

Слайд 21Self-deception strategies

Self Serving Bias (mentioned in the previous lecture)

More skeptical of

Comparisons to those slightly worse

Skew impressions of others to highlight

own good traits as unusual

Слайд 22Self-awareness

Private self-awareness

refers to attending to your inner states, including emotions,

Рublic self-awareness

means attending to how you are perceived by others, including

what others might think of you.

Слайд 23Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring is the degree to which you are aware of how

Observing one’s own behavior and adapting it to the situation

Слайд 24 Self-Monitoring

What are the dangers of being a:

High Self-Monitor (adjusts behavior

Low Self-Monitor (principled attitudes guide behaviour)

High self-monitors regulate their expressive self-presentation in order to present the desired public appearance. These individuals may be considered to be insincere chameleons.

Low self-monitors lack either the ability or the motivation to regulate their expressive self-presentations. These individuals may be viewed as insensitive.

Слайд 25Is high or low-self-monitoring related to job success?

Research (meta-analysis) has shown

Слайд 26Benefits of high self-esteem

Feels good

Helps one to overcome bad feelings

If

Слайд 27Self-esteem

Self-esteem reflects a person's overall subjective emotional evaluation of his or

"The self-concept is what we think about the self; self-esteem, is the positive or negative evaluations of the self, as in how we feel about it” (Smith, E. R.; Mackie, D. M. (2007). Social Psychology (Third ed.). Hove: Psychology Press)

Слайд 28Benefits of high self-esteem

Feels good

Helps one to overcome bad feelings

If

Слайд 29Benefits of high self-esteem

Feels good

Helps one to overcome bad feelings

If

Schwarzenegger: “If you try ten times, you have a better chance of

making it on the eleventh try than if you didn’t try at all”

Healthy to have a slightly inflated sense of self-value

Слайд 30Self-esteem

Self-esteem serves as a sociometer for one’s standing

in a group.

Sociometer

This theoretical perspective was first introduced by

Mark Leary and colleagues in 1995 and later expanded

on by Kirkpatrick and Ellis (2001).

Слайд 31Why do we care about self-esteem?

Self-esteem is a measure of social

A sociometer (made from the words social and meter) is a measure

of how desirable one would be to other people as a relationship

partner, team member, employee, colleague, or in some other way.

In this sense, self-esteem is a sociometer because it measures

the traits you have according to how much they qualify you for

social acceptance. Sociometer theory can explain why people are

so concerned with self-esteem: It helps people navigate

the long road to social acceptance.

Слайд 32Why do we care about self-esteem?

Self-esteem is a measure of social

Mark Leary, the author of sociometer theory, compares self-esteem to the gas gauge on a car. A gas gauge may seem trivial because it doesn’t make the car go forward. But the gas gauge tells you about something that is important—namely, whether there is enough

fuel in the car.

Just as drivers act out of concern to keep their gas gauge above zero, so people seem constantly to act so as to preserve their self-esteem.

Слайд 33

A common view is that self-esteem is based mainly on

However, recent evidence suggests that feeling accepted has a bigger impact on self-esteem than does feeling competent (though both matter).

Слайд 34Negative aspects of highest self-esteem

Narcissism

Subset of high self-esteem

Tend to be more

Higher prejudice

Tend to think their group is better

Слайд 35Self-efficacy

Belief in one’s capacity to succeed at a given task.

e.g. Public

Bandura recommended specific rather than general

measures of Self-efficacy.

Bandura, A. (1994). Self‐efficacy. John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

Слайд 36Effects of High Self-Efficacy

Prior

Experience

Sources of Self-Efficacy Beliefs

Feedback

Behavioral Patterns

Results

High

“I know

can do this job”

Self-efficacy

beliefs

Success

Behavior

Models

Persuasion

from Others

Assessment of

physical/

emotional

state

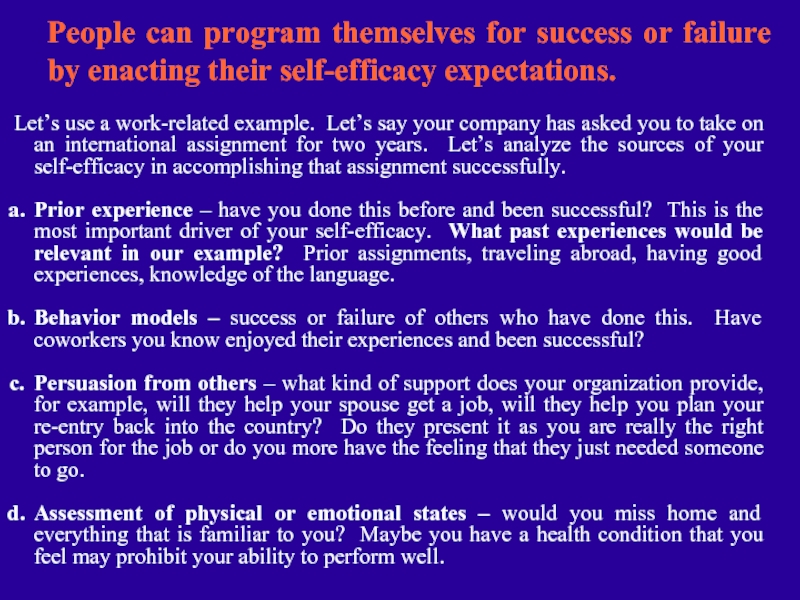

Слайд 37People can program themselves for success or failure by enacting their

Let’s use a work-related example. Let’s say your company has asked you to take on an international assignment for two years. Let’s analyze the sources of your self-efficacy in accomplishing that assignment successfully.

Prior experience – have you done this before and been successful? This is the most important driver of your self-efficacy. What past experiences would be relevant in our example? Prior assignments, traveling abroad, having good experiences, knowledge of the language.

Behavior models – success or failure of others who have done this. Have coworkers you know enjoyed their experiences and been successful?

Persuasion from others – what kind of support does your organization provide, for example, will they help your spouse get a job, will they help you plan your re-entry back into the country? Do they present it as you are really the right person for the job or do you more have the feeling that they just needed someone to go.

Assessment of physical or emotional states – would you miss home and everything that is familiar to you? Maybe you have a health condition that you feel may prohibit your ability to perform well.

Слайд 38Effects of High Self-Efficacy

Prior

Experience

Sources of Self-Efficacy Beliefs

Feedback

Behavioral Patterns

Results

High

“I know

can do this job”

Self-efficacy

beliefs

Success

Behavior

Models

Persuasion

from Others

Assessment of

physical/

emotional

state

Слайд 39Effects of Low Self-Efficacy

Sources of Self-Efficacy Beliefs

Feedback

Behavioral Patterns

Results

Self-efficacy

beliefs

Low

“I don’t think

I can

done”

Failure

Prior

Experience

Behavior

Models

Persuasion

from Others

Assessment of

physical/

emotional

state

Слайд 44Interpersonal self

self – presentation

Behaviors that convey an image to others

Public esteem

More

Слайд 45Functions of self-presentation

Social acceptance

Increase chance of acceptance and maintain

place within

Claiming identity

Social validation of claims to identity

Слайд 46Interpersonal Self

The idea that cultural styles of selfhood differ along the

They proposed that Asians differ from North Americans and Europeans in how they think of themselves and how they seek to construct the self in relation to others.

To avoid the overused term self-concept, they introduced the term self-construal, which means a way of thinking about the self.

Слайд 47self-construal

Markus and Kitayama (1991) published their classic article on culture and

Слайд 48self-construal

They argued that Western cultures are unusual in promoting an independent

Слайд 49Interdependent of Self-Concept

In individualistic cultures it is expected that people will

Men are expected to have an independent self-concept more than women.

In collectivist cultures it is expected that people will develop a self-concept in terms of their connections or relationships with others.

Women are expected to have an interdependent self-concept more than men.

Слайд 50self-construal

They proposed that people with independent self-construals would

strive for self-expression, uniqueness,

In contrast, people with interdependent self-construals would strive to fit in and maintain social harmony, basing their actions on situationally defined norms and expectations.

Слайд 52self-construal

Markus and Kitayama’s (1991) proposals had a dramatic impact on social,

Слайд 53self-construal

Their work may have added scientific legitimacy to a common tendency

Concurrently, an empirical focus on comparing “Western” (usually North American) and “Eastern” usually East Asian) samples has often left the cultural systems of other world regions relatively marginalized within the scientific discourse on culture and self (for an example, see Yamaguchi et al., 2007).

This narrow focus may have restricted theorizing and thus limited the explanatory potential of self-construals.

Слайд 54

Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

Слайд 55Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy:

Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

Markus and

Слайд 56Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy:

Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

We sampled

In Study 2, we tested and confirmed this new theoretical model among adult participants from over 50 cultural contexts

Слайд 57Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy:

Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

We tested

Rather than equating ‘culture’ with ‘nation’, we targeted several cultural groups within each nation where relevant and feasible. The nature of the groups varied from nation to nation, such that the differences might be regional (e.g., Eastern and Western Germany), religious (e.g., Baptists and Orthodox Christians in Georgia) or ethnic (e.g., Damara and Owambo in Namibia). We collected data from over 7,000 adult members of 55 cultural groups in 33 nations, spanning all inhabited continents.

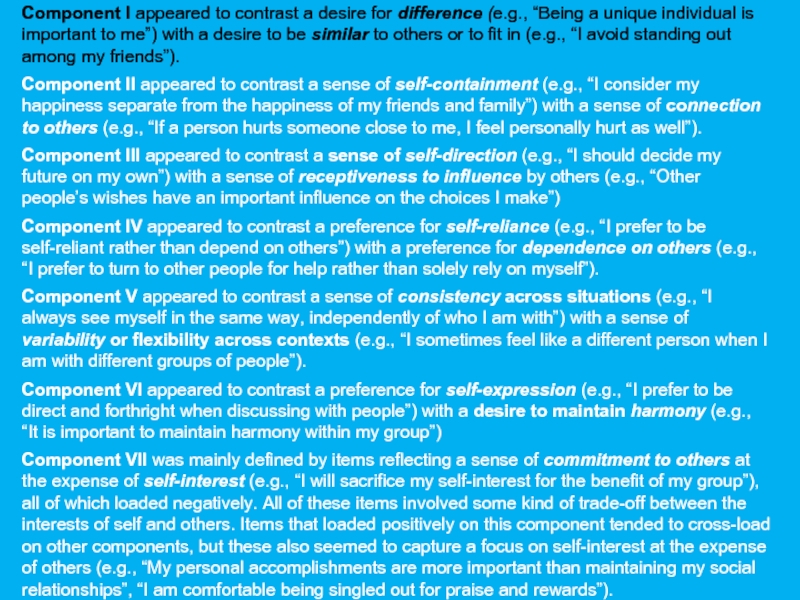

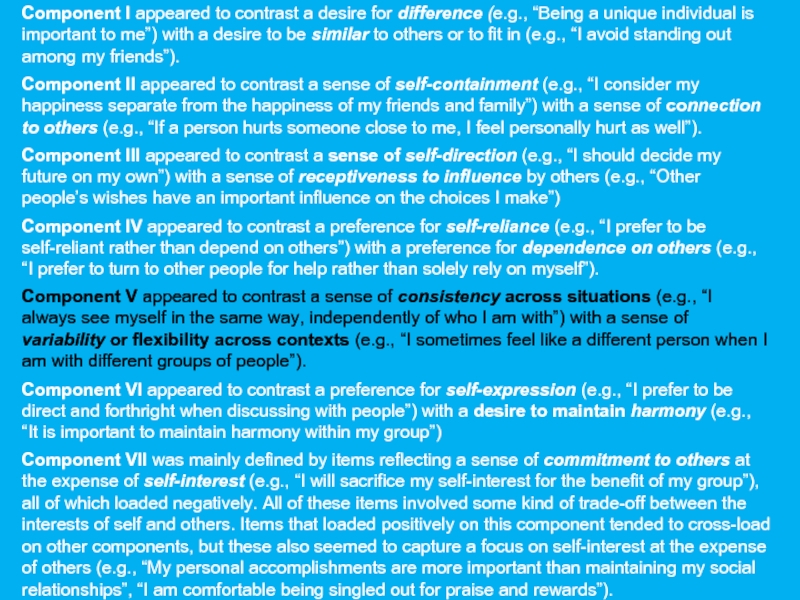

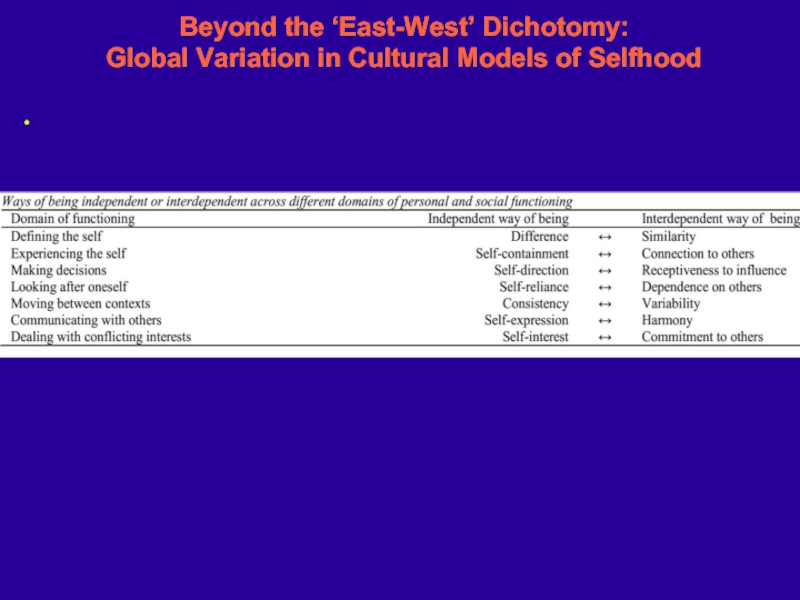

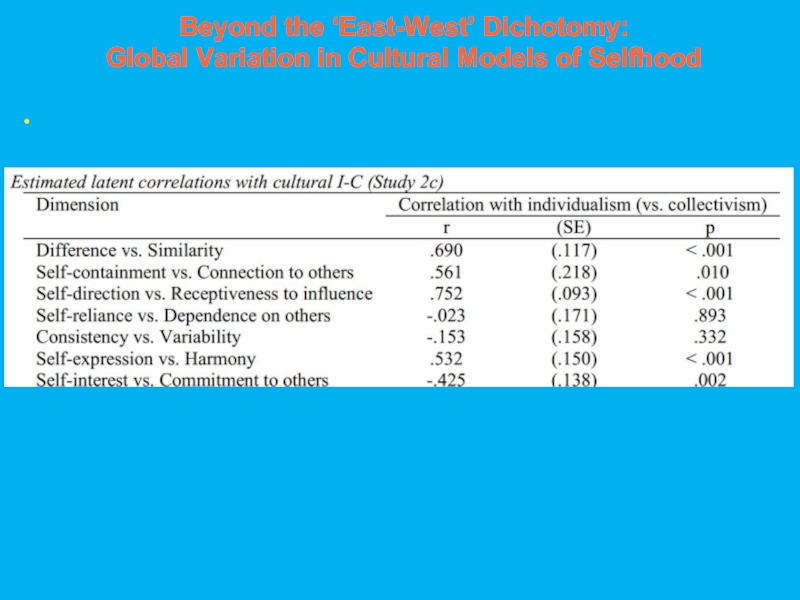

Слайд 60Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being

Component II appeared to contrast a sense of self-containment (e.g., “I consider my happiness separate from the happiness of my friends and family”) with a sense of connection to others (e.g., “If a person hurts someone close to me, I feel personally hurt as well”).

Component III appeared to contrast a sense of self-direction (e.g., “I should decide my future on my own”) with a sense of receptiveness to influence by others (e.g., “Other people’s wishes have an important influence on the choices I make”)

Component IV appeared to contrast a preference for self-reliance (e.g., “I prefer to be self-reliant rather than depend on others”) with a preference for dependence on others (e.g., “I prefer to turn to other people for help rather than solely rely on myself”).

Component V appeared to contrast a sense of consistency across situations (e.g., “I always see myself in the same way, independently of who I am with”) with a sense of variability or flexibility across contexts (e.g., “I sometimes feel like a different person when I am with different groups of people”).

Component VI appeared to contrast a preference for self-expression (e.g., “I prefer to be direct and forthright when discussing with people”) with a desire to maintain harmony (e.g., “It is important to maintain harmony within my group”)

Component VII was mainly defined by items reflecting a sense of commitment to others at the expense of self-interest (e.g., “I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of my group”), all of which loaded negatively. All of these items involved some kind of trade-off between the interests of self and others. Items that loaded positively on this component tended to cross-load on other components, but these also seemed to capture a focus on self-interest at the expense of others (e.g., “My personal accomplishments are more important than maintaining my social relationships”, “I am comfortable being singled out for praise and rewards”).

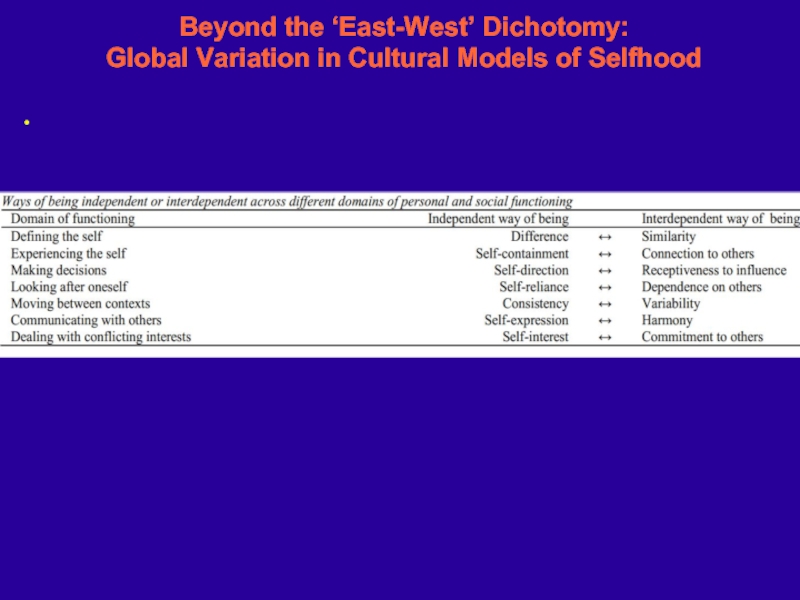

Слайд 62Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being

Component II appeared to contrast a sense of self-containment (e.g., “I consider my happiness separate from the happiness of my friends and family”) with a sense of connection to others (e.g., “If a person hurts someone close to me, I feel personally hurt as well”).

Component III appeared to contrast a sense of self-direction (e.g., “I should decide my future on my own”) with a sense of receptiveness to influence by others (e.g., “Other people’s wishes have an important influence on the choices I make”)

Component IV appeared to contrast a preference for self-reliance (e.g., “I prefer to be self-reliant rather than depend on others”) with a preference for dependence on others (e.g., “I prefer to turn to other people for help rather than solely rely on myself”).

Component V appeared to contrast a sense of consistency across situations (e.g., “I always see myself in the same way, independently of who I am with”) with a sense of variability or flexibility across contexts (e.g., “I sometimes feel like a different person when I am with different groups of people”).

Component VI appeared to contrast a preference for self-expression (e.g., “I prefer to be direct and forthright when discussing with people”) with a desire to maintain harmony (e.g., “It is important to maintain harmony within my group”)

Component VII was mainly defined by items reflecting a sense of commitment to others at the expense of self-interest (e.g., “I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of my group”), all of which loaded negatively. All of these items involved some kind of trade-off between the interests of self and others. Items that loaded positively on this component tended to cross-load on other components, but these also seemed to capture a focus on self-interest at the expense of others (e.g., “My personal accomplishments are more important than maintaining my social relationships”, “I am comfortable being singled out for praise and rewards”).

Слайд 64Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being

Component II appeared to contrast a sense of self-containment (e.g., “I consider my happiness separate from the happiness of my friends and family”) with a sense of connection to others (e.g., “If a person hurts someone close to me, I feel personally hurt as well”).

Component III appeared to contrast a sense of self-direction (e.g., “I should decide my future on my own”) with a sense of receptiveness to influence by others (e.g., “Other people’s wishes have an important influence on the choices I make”)

Component IV appeared to contrast a preference for self-reliance (e.g., “I prefer to be self-reliant rather than depend on others”) with a preference for dependence on others (e.g., “I prefer to turn to other people for help rather than solely rely on myself”).

Component V appeared to contrast a sense of consistency across situations (e.g., “I always see myself in the same way, independently of who I am with”) with a sense of variability or flexibility across contexts (e.g., “I sometimes feel like a different person when I am with different groups of people”).

Component VI appeared to contrast a preference for self-expression (e.g., “I prefer to be direct and forthright when discussing with people”) with a desire to maintain harmony (e.g., “It is important to maintain harmony within my group”)

Component VII was mainly defined by items reflecting a sense of commitment to others at the expense of self-interest (e.g., “I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of my group”), all of which loaded negatively. All of these items involved some kind of trade-off between the interests of self and others. Items that loaded positively on this component tended to cross-load on other components, but these also seemed to capture a focus on self-interest at the expense of others (e.g., “My personal accomplishments are more important than maintaining my social relationships”, “I am comfortable being singled out for praise and rewards”).

Слайд 66Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being

Component II appeared to contrast a sense of self-containment (e.g., “I consider my happiness separate from the happiness of my friends and family”) with a sense of connection to others (e.g., “If a person hurts someone close to me, I feel personally hurt as well”).

Component III appeared to contrast a sense of self-direction (e.g., “I should decide my future on my own”) with a sense of receptiveness to influence by others (e.g., “Other people’s wishes have an important influence on the choices I make”)

Component IV appeared to contrast a preference for self-reliance (e.g., “I prefer to be self-reliant rather than depend on others”) with a preference for dependence on others (e.g., “I prefer to turn to other people for help rather than solely rely on myself”).

Component V appeared to contrast a sense of consistency across situations (e.g., “I always see myself in the same way, independently of who I am with”) with a sense of variability or flexibility across contexts (e.g., “I sometimes feel like a different person when I am with different groups of people”).

Component VI appeared to contrast a preference for self-expression (e.g., “I prefer to be direct and forthright when discussing with people”) with a desire to maintain harmony (e.g., “It is important to maintain harmony within my group”)

Component VII was mainly defined by items reflecting a sense of commitment to others at the expense of self-interest (e.g., “I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of my group”), all of which loaded negatively. All of these items involved some kind of trade-off between the interests of self and others. Items that loaded positively on this component tended to cross-load on other components, but these also seemed to capture a focus on self-interest at the expense of others (e.g., “My personal accomplishments are more important than maintaining my social relationships”, “I am comfortable being singled out for praise and rewards”).

Слайд 68Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being

Component II appeared to contrast a sense of self-containment (e.g., “I consider my happiness separate from the happiness of my friends and family”) with a sense of connection to others (e.g., “If a person hurts someone close to me, I feel personally hurt as well”).

Component III appeared to contrast a sense of self-direction (e.g., “I should decide my future on my own”) with a sense of receptiveness to influence by others (e.g., “Other people’s wishes have an important influence on the choices I make”)

Component IV appeared to contrast a preference for self-reliance (e.g., “I prefer to be self-reliant rather than depend on others”) with a preference for dependence on others (e.g., “I prefer to turn to other people for help rather than solely rely on myself”).

Component V appeared to contrast a sense of consistency across situations (e.g., “I always see myself in the same way, independently of who I am with”) with a sense of variability or flexibility across contexts (e.g., “I sometimes feel like a different person when I am with different groups of people”).

Component VI appeared to contrast a preference for self-expression (e.g., “I prefer to be direct and forthright when discussing with people”) with a desire to maintain harmony (e.g., “It is important to maintain harmony within my group”)

Component VII was mainly defined by items reflecting a sense of commitment to others at the expense of self-interest (e.g., “I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of my group”), all of which loaded negatively. All of these items involved some kind of trade-off between the interests of self and others. Items that loaded positively on this component tended to cross-load on other components, but these also seemed to capture a focus on self-interest at the expense of others (e.g., “My personal accomplishments are more important than maintaining my social relationships”, “I am comfortable being singled out for praise and rewards”).

Слайд 70Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being

Component II appeared to contrast a sense of self-containment (e.g., “I consider my happiness separate from the happiness of my friends and family”) with a sense of connection to others (e.g., “If a person hurts someone close to me, I feel personally hurt as well”).

Component III appeared to contrast a sense of self-direction (e.g., “I should decide my future on my own”) with a sense of receptiveness to influence by others (e.g., “Other people’s wishes have an important influence on the choices I make”)

Component IV appeared to contrast a preference for self-reliance (e.g., “I prefer to be self-reliant rather than depend on others”) with a preference for dependence on others (e.g., “I prefer to turn to other people for help rather than solely rely on myself”).

Component V appeared to contrast a sense of consistency across situations (e.g., “I always see myself in the same way, independently of who I am with”) with a sense of variability or flexibility across contexts (e.g., “I sometimes feel like a different person when I am with different groups of people”).

Component VI appeared to contrast a preference for self-expression (e.g., “I prefer to be direct and forthright when discussing with people”) with a desire to maintain harmony (e.g., “It is important to maintain harmony within my group”)

Component VII was mainly defined by items reflecting a sense of commitment to others at the expense of self-interest (e.g., “I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of my group”), all of which loaded negatively. All of these items involved some kind of trade-off between the interests of self and others. Items that loaded positively on this component tended to cross-load on other components, but these also seemed to capture a focus on self-interest at the expense of others (e.g., “My personal accomplishments are more important than maintaining my social relationships”, “I am comfortable being singled out for praise and rewards”).

Слайд 72Component I appeared to contrast a desire for difference (e.g., “Being

Component II appeared to contrast a sense of self-containment (e.g., “I consider my happiness separate from the happiness of my friends and family”) with a sense of connection to others (e.g., “If a person hurts someone close to me, I feel personally hurt as well”).

Component III appeared to contrast a sense of self-direction (e.g., “I should decide my future on my own”) with a sense of receptiveness to influence by others (e.g., “Other people’s wishes have an important influence on the choices I make”)

Component IV appeared to contrast a preference for self-reliance (e.g., “I prefer to be self-reliant rather than depend on others”) with a preference for dependence on others (e.g., “I prefer to turn to other people for help rather than solely rely on myself”).

Component V appeared to contrast a sense of consistency across situations (e.g., “I always see myself in the same way, independently of who I am with”) with a sense of variability or flexibility across contexts (e.g., “I sometimes feel like a different person when I am with different groups of people”).

Component VI appeared to contrast a preference for self-expression (e.g., “I prefer to be direct and forthright when discussing with people”) with a desire to maintain harmony (e.g., “It is important to maintain harmony within my group”)

Component VII was partly defined by items reflecting a sense of commitment to others at the expense of self-interest (e.g., “I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of my group”) and items describing a focus on self-interest at the expense of others (e.g., “My personal accomplishments are more important than maintaining my social relationships”, “I am comfortable being singled out for praise and rewards”).

Слайд 75Beyond the ‘East-West’ Dichotomy:

Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood

In closing,

Слайд 78The Forer effect (also called the Barnum effect after P. T.

THE “FORER EFFECT” (Barnum effect)

Слайд 79This effect can provide a partial explanation for the widespread acceptance

A related and more general phenomenon is that of subjective validation.

Subjective validation occurs when two unrelated or even random events are perceived to be related because a belief, expectation, or hypothesis demands a relationship. Thus people seek a correspondence between their perception of their personality and the contents of a horoscope.

THE “FORER EFFECT” (Barnum effect)

Слайд 80Psychologist Bertram R. Forer gave a personality test to his students.

Слайд 81On average, the students rated its accuracy as 4.26 on a

Only after the ratings were turned in was it revealed that each student had received identical copies assembled by Forer from a newsstand astrology book. The quote contains a number of statements that are vague and general enough to apply to a wide range of people.

THE “FORER EFFECT” (Barnum effect)

Слайд 82THE “FORER EFFECT” (Barnum effect)

Subjects give higher accuracy ratings if...

○ The

○ The subject believes in the authority of the evaluator

○ The analysis lists mostly positive traits, or turns

weaknesses into strengths (more positive more acceptable)