- Главная

- Разное

- Дизайн

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Аналитика

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Красота и здоровье

- Финансы

- Государство

- Путешествия

- Спорт

- Недвижимость

- Армия

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Culture and cognition презентация

Содержание

- 1. Culture and cognition

- 2. Outline Introduction Visual illusions Pictorial perception 4.

- 3. Readings Berry, et al

- 4. 1. Introduction The field of study called

- 5. 1. Introduction The 1899 expedition to

- 8. 2. Visual Illusion Susceptibility One of the

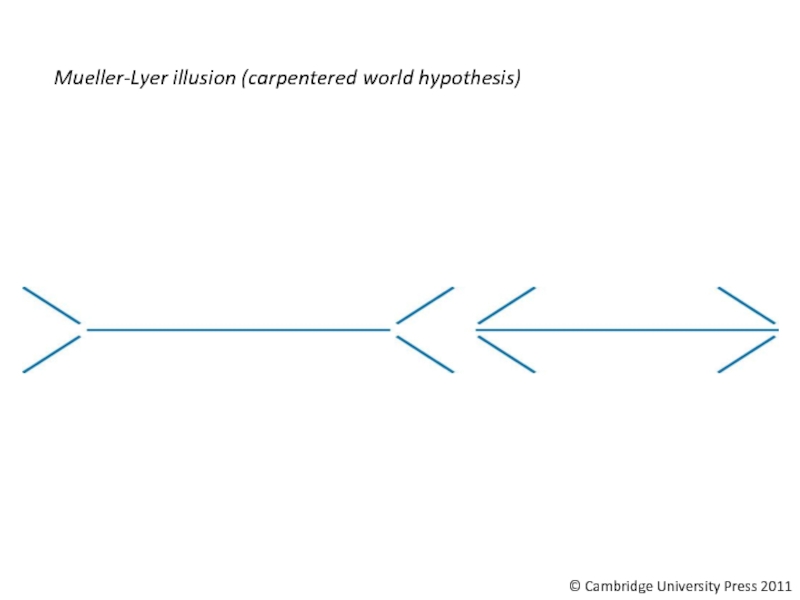

- 9. 2. Carpentered World Hypothesis Susceptibility to

- 10. © Cambridge University Press 2011 Mueller-Lyer illusion (carpentered world hypothesis)

- 11. © Cambridge University Press 2011 Sander parallelogram (carpentered world hypothesis)

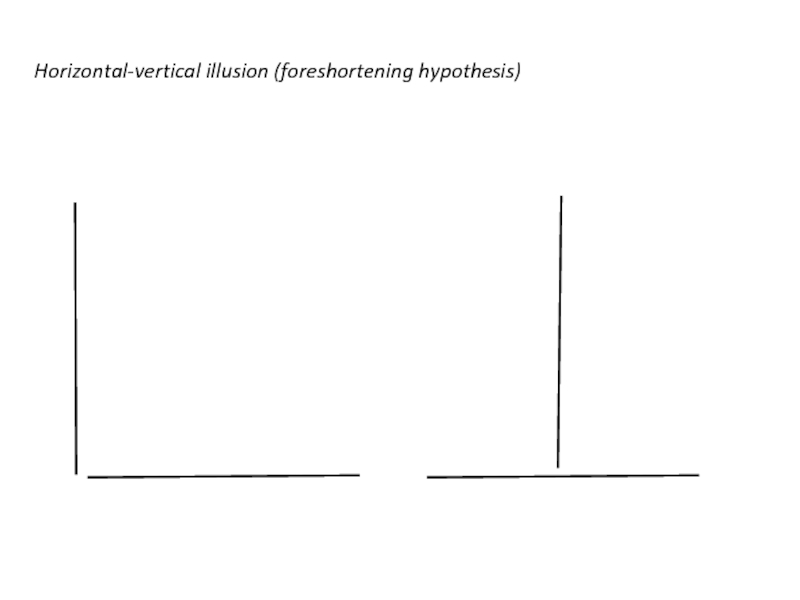

- 12. 2. Foreshortening Hypothesis Susceptibility to the

- 13. Horizontal-vertical illusion (foreshortening hypothesis)

- 14. 3. Perception of Depth in Pictures

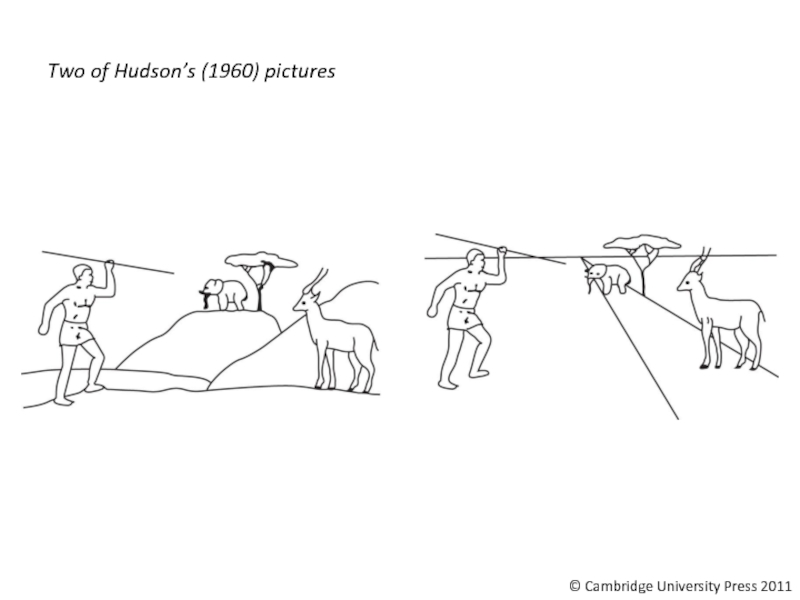

- 15. © Cambridge University Press 2011 Two of Hudson’s (1960) pictures

- 16. 3. Perception of Depth in Pictures

- 17. 4. Cognition -Introduction The study of cognition,

- 18. 4. Intelligence There are three explanatory frames

- 19. 4. General Intelligence There is evidence that

- 20. 4. General Intelligence Many criticisms have been

- 21. 4. General Intelligence The tradition of claiming

- 22. Lynn (2006): World Distribution of Intelligence

- 23. 4.2 Indigenous Conceptions of Intelligence Most

- 25. 5. Cognitive Styles Cognitive styles are a

- 26. 5.1. Field Dependence-Independence Witkin found that a

- 27. 5.1. Field Dependence-Independence The construct of

- 28. 5.1 Field Dependence-Independence The cognitive style of

- 29. 5.1 Field Dependence-Independence * Research has found

- 30. 5.1 Field Dependence-Independence

- 31. 5. 1 Cognitive Styles African Embedded Figures

- 33. 5.1 Cognitive Styles Although sometimes used as

- 35. 5.2. East / West Cognitive Styles

- 36. 5.2. East / West Cognitive Styles He

- 37. 5.2. East/ West Cognitive Styles In this

- 38. 5.2. East/ West Cognitive Styles Nisbett denies

- 39. 5.2. East/ West Cognitive Styles These

- 40. 5.2. East/ West Cognitive Styles

- 41. 5.2. East/West Cognitive Styles Two

- 42. 6. Conclusion Perception and cognition are activities

Слайд 2Outline

Introduction

Visual illusions

Pictorial perception

4. Intelligence across cultures

4.1 General

Intelligence ‘g’

4.2 Indigenous conceptions

5. Cognitive styles:

5.1 Field dependence/independence

5.2 East/ West styles

6. Conclusions

4.2 Indigenous conceptions

5. Cognitive styles:

5.1 Field dependence/independence

5.2 East/ West styles

6. Conclusions

Слайд 3 Readings

Berry, et al (2011). Cross-cultural Psychology. Chapters 9 and 6.

Segall,

M. H., Campbell, D. T., & Herskovits, K. J. (1966). The influence of culture on visual perception. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

Berry, J.W., and Dasen, P. (1974) (Eds.). Culture and Cognition, London: Methuen found

Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently … and why. New York: The Free Press

Berry, J.W., and Dasen, P. (1974) (Eds.). Culture and Cognition, London: Methuen found

Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently … and why. New York: The Free Press

Слайд 41. Introduction

The field of study called culture and cognition includes a

number of related phenomena: sensation, perception, intelligence and cognitive style.

Sensation and perception were one of the earliest areas of psychology to be examined across cultures.

Sensation and perception were one of the earliest areas of psychology to be examined across cultures.

Слайд 51. Introduction

The 1899 expedition to the Torres Strait Islands by Rivers

examined a number of phenomena, including colour perception and the susceptibility of these peoples to visual illusions.

The belief at that time was that these ‘savages’ would be tricked more easily that would Cambridge undergraduates.

However, the findings were more complicated!

The belief at that time was that these ‘savages’ would be tricked more easily that would Cambridge undergraduates.

However, the findings were more complicated!

Слайд 82. Visual Illusion Susceptibility

One of the classics of ccp are studies

of susceptibility to visual illusions (Segall, Campbell & Herskovits, 1962, 1966)

They examined 2 theory-derived hypotheses, checked the relevant (external) cultural conditions and analyzed their data

They had data collected by colleagues around the world [in 14 non-western and 3 western contexts], using a well-designed stimulus book.

The two hypotheses were:

carpentered world hypothesis;

foreshortening hypothesis

Both hypotheses are based on the view that we respond to visual illusions on the basis of what we have learned in our visual ecology

They examined 2 theory-derived hypotheses, checked the relevant (external) cultural conditions and analyzed their data

They had data collected by colleagues around the world [in 14 non-western and 3 western contexts], using a well-designed stimulus book.

The two hypotheses were:

carpentered world hypothesis;

foreshortening hypothesis

Both hypotheses are based on the view that we respond to visual illusions on the basis of what we have learned in our visual ecology

Слайд 92. Carpentered World Hypothesis

Susceptibility to angled illusions [such as the Muller-Lyer

arrows, and the Sander parallelogram] is promoted by living in visual environments that are carpentered to produce many right angles.

Perceivers are ‘tricked’ by interpreting these acute and obtuse angles as right angles.

In the ML, they overestimate the length of the line subtended by the outward pointing arrows

In the Sander, they over estimate the length of the line subtended between the obtuse angles

Perceivers are ‘tricked’ by interpreting these acute and obtuse angles as right angles.

In the ML, they overestimate the length of the line subtended by the outward pointing arrows

In the Sander, they over estimate the length of the line subtended between the obtuse angles

Слайд 122. Foreshortening Hypothesis

Susceptibility to the horizontal-vertical illusion is promoted for people

who experience long distances in a horizontal plane, and having few verticals.

Perceivers are ‘tricked’ into interpreting a vertical stimulus as a long line running away from them in the horizontal plane.

They thus overestimate the length of the vertical line in relation to the horizontal line.

Perceivers are ‘tricked’ into interpreting a vertical stimulus as a long line running away from them in the horizontal plane.

They thus overestimate the length of the vertical line in relation to the horizontal line.

Слайд 143. Perception of Depth in Pictures

The recognition of objects in drawings

requires previous experience of drawings and the conventions used to represent objects.

Hudson studied one aspect of pictorial perception [depth perception pictures ] in South Africa using drawings of animals and topography.

He began this line of work to improve communication of safe working practices in mine workers.

Hudson studied one aspect of pictorial perception [depth perception pictures ] in South Africa using drawings of animals and topography.

He began this line of work to improve communication of safe working practices in mine workers.

Слайд 163. Perception of Depth in Pictures

The perception of depth involves depth

cues:

- relative size,

- superposition,

- gradient of texture, and

- perspective.

Some of these require more exposure to be learned than others:

- for example the gradient of texture is usually compelling by

itself

- in contrast linear perspective qualifies as a cultural

convention

Hudson concluded that aspects of 3D perception of 2D figures are based on a set of learned skills in particular cultural contexts.

- relative size,

- superposition,

- gradient of texture, and

- perspective.

Some of these require more exposure to be learned than others:

- for example the gradient of texture is usually compelling by

itself

- in contrast linear perspective qualifies as a cultural

convention

Hudson concluded that aspects of 3D perception of 2D figures are based on a set of learned skills in particular cultural contexts.

Слайд 174. Cognition -Introduction

The study of cognition, cognitive abilities and intelligence has

been controversial for many years.

The notion that there is only one kind of intelligence is problematic, because there are many culturally- based (indigenous) conceptions.

Despite these problems, the concept of general intelligence continues to be used across cultures.

The notions of cognitive style has come to replace intelligence in much c-c research .

The notion that there is only one kind of intelligence is problematic, because there are many culturally- based (indigenous) conceptions.

Despite these problems, the concept of general intelligence continues to be used across cultures.

The notions of cognitive style has come to replace intelligence in much c-c research .

Слайд 184. Intelligence

There are three explanatory frames that were historically used to

describe or interpret the intelligence of “primitive peoples”:

-Climate: During the Enlightenment temperate climate

(eg., Europe) was seen as more conducive to high

civilization than tropical or arctic regions

- “Race”: In the 19th century theories of social and

cultural evolution developed

- Culture: In the 20th century “culture” gained

prominence, with a shift in emphasis

-Climate: During the Enlightenment temperate climate

(eg., Europe) was seen as more conducive to high

civilization than tropical or arctic regions

- “Race”: In the 19th century theories of social and

cultural evolution developed

- Culture: In the 20th century “culture” gained

prominence, with a shift in emphasis

Слайд 194. General Intelligence

There is evidence that many tests of cognitive ability

are correlated, leading to the concept of a general cognitive capacity, called "g" .

Many studies have attempted to compare ‘g’ across cultures, but have experienced serious problems with equivalence and comparability.

Nevertheless, “racial” differences in studies in the USA on “g” have been inferred from intelligence test score

The core problem is that individual level heritability cannot applied to culture-level data.

Many studies have attempted to compare ‘g’ across cultures, but have experienced serious problems with equivalence and comparability.

Nevertheless, “racial” differences in studies in the USA on “g” have been inferred from intelligence test score

The core problem is that individual level heritability cannot applied to culture-level data.

Слайд 204. General Intelligence

Many criticisms have been raised about such studies:

- A distinction has to be made between intelligence A, B, C:

A-genetic equipment and potentiality

B-the results of its development through interaction with culture

C- actual performance on an intelligent tests

- There are important changes in mean group performance

over time (Flynn effect)

- Cross-cultural equivalence is difficult to achieve

- the “g” loading is correlated with “culture” loading

- Stimulus familiarity affects processing even with simple

tasks

A-genetic equipment and potentiality

B-the results of its development through interaction with culture

C- actual performance on an intelligent tests

- There are important changes in mean group performance

over time (Flynn effect)

- Cross-cultural equivalence is difficult to achieve

- the “g” loading is correlated with “culture” loading

- Stimulus familiarity affects processing even with simple

tasks

Слайд 214. General Intelligence

The tradition of claiming that there is one kind

of intelligence (quality) that varies in development (competence) and expression (quantity/ performance) is exemplified by the work of Lynn and colleagues.

This is the absolutist perspective

They take IQ scores from a variety of studies and interpret them as valid estimates of intelligence.

These ‘findings’ are unsound, and without any known validity.

Nevertheless, they are popular among non-psychologists.

This is the absolutist perspective

They take IQ scores from a variety of studies and interpret them as valid estimates of intelligence.

These ‘findings’ are unsound, and without any known validity.

Nevertheless, they are popular among non-psychologists.

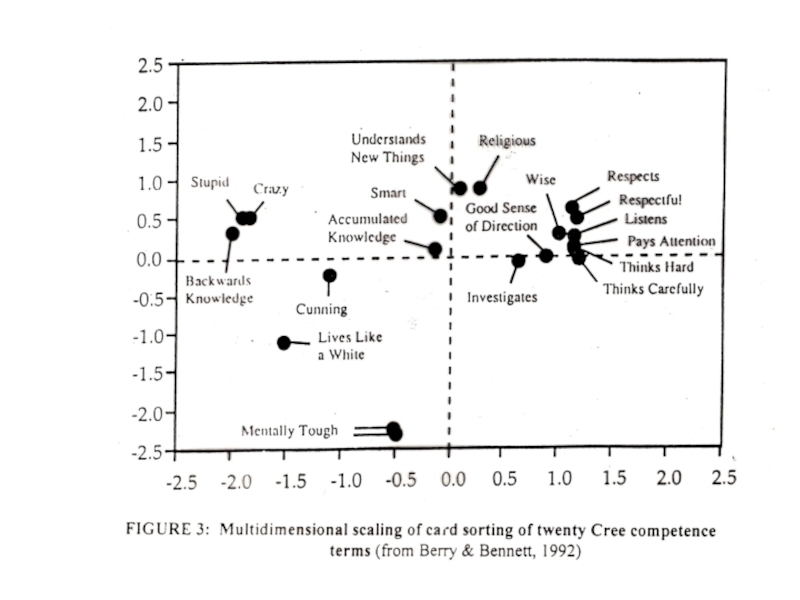

Слайд 234.2 Indigenous Conceptions

of Intelligence

Most cultures have a clear notion of

what they consider to be a competent or intelligent person.

Many studies have examined these indigenous conceptions, which have large variation.

One of these, described in the textbook by Berry and Bennett, 1992.

They found that for the Cree people of northern Canada, the core quality is that of respect

Many studies have examined these indigenous conceptions, which have large variation.

One of these, described in the textbook by Berry and Bennett, 1992.

They found that for the Cree people of northern Canada, the core quality is that of respect

Слайд 255. Cognitive Styles

Cognitive styles are a person’s preferred way of processing

information and dealing with day-to-day tasks.

They serve as ways of organizing and using cognitive information that allow a cultural group and its members to deal effectively with problems encountered in daily living.

There is evidence that individuals in all cultures have the processes required to deal with information in their environments.

The cognitive styles approach allows for the comparison of cognitive competence or performance across cultural groups, without the use of some absolute criterion (such as ‘g’ in the general intelligence approach)

They serve as ways of organizing and using cognitive information that allow a cultural group and its members to deal effectively with problems encountered in daily living.

There is evidence that individuals in all cultures have the processes required to deal with information in their environments.

The cognitive styles approach allows for the comparison of cognitive competence or performance across cultural groups, without the use of some absolute criterion (such as ‘g’ in the general intelligence approach)

Слайд 265.1. Field Dependence-Independence

Witkin found that a number of abilities were related

to each other in a way that evidenced a “pattern,” namely the tendency to rely primarily on internal (as opposed to external) frames of reference when orienting oneself in space.

The FDI cognitive style is referred to by Witkin as the “extent of autonomous functioning.”

The FDI cognitive style is referred to by Witkin as the “extent of autonomous functioning.”

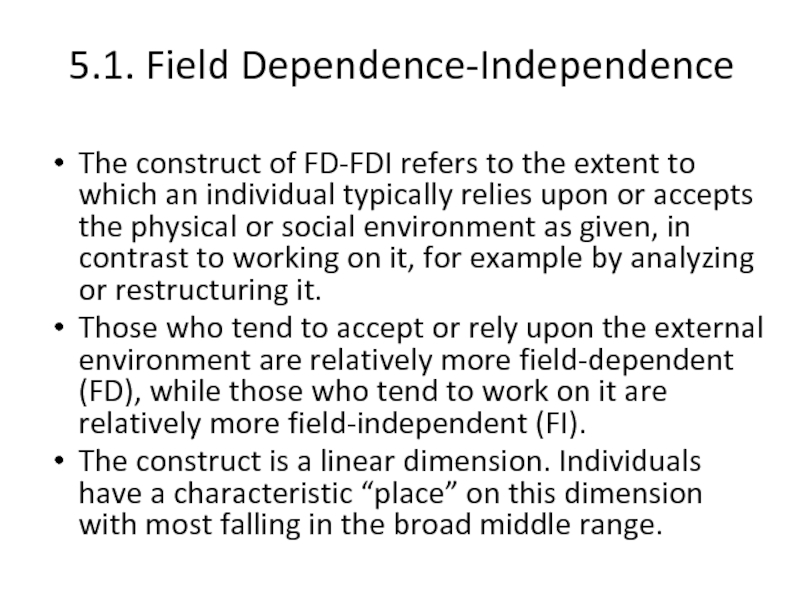

Слайд 275.1. Field Dependence-Independence

The construct of FD-FDI refers to the extent to

which an individual typically relies upon or accepts the physical or social environment as given, in contrast to working on it, for example by analyzing or restructuring it.

Those who tend to accept or rely upon the external environment are relatively more field-dependent (FD), while those who tend to work on it are relatively more field-independent (FI).

The construct is a linear dimension. Individuals have a characteristic “place” on this dimension with most falling in the broad middle range.

Those who tend to accept or rely upon the external environment are relatively more field-dependent (FD), while those who tend to work on it are relatively more field-independent (FI).

The construct is a linear dimension. Individuals have a characteristic “place” on this dimension with most falling in the broad middle range.

Слайд 285.1 Field Dependence-Independence

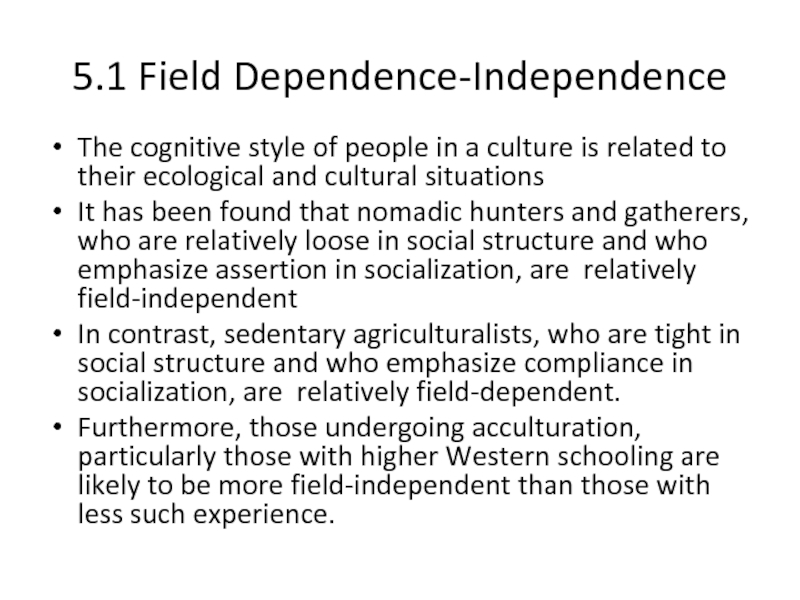

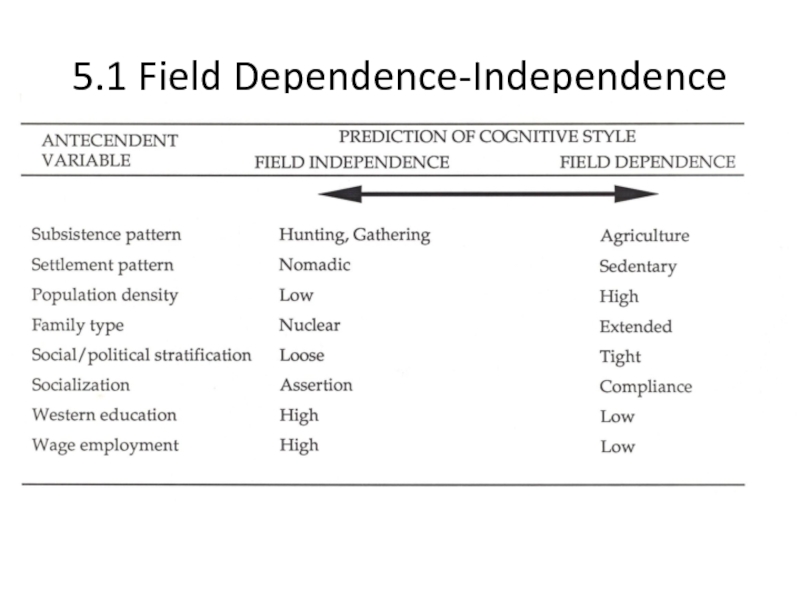

The cognitive style of people in a culture is

related to their ecological and cultural situations

It has been found that nomadic hunters and gatherers, who are relatively loose in social structure and who emphasize assertion in socialization, are relatively field-independent

In contrast, sedentary agriculturalists, who are tight in social structure and who emphasize compliance in socialization, are relatively field-dependent.

Furthermore, those undergoing acculturation, particularly those with higher Western schooling are likely to be more field-independent than those with less such experience.

It has been found that nomadic hunters and gatherers, who are relatively loose in social structure and who emphasize assertion in socialization, are relatively field-independent

In contrast, sedentary agriculturalists, who are tight in social structure and who emphasize compliance in socialization, are relatively field-dependent.

Furthermore, those undergoing acculturation, particularly those with higher Western schooling are likely to be more field-independent than those with less such experience.

Слайд 295.1 Field Dependence-Independence

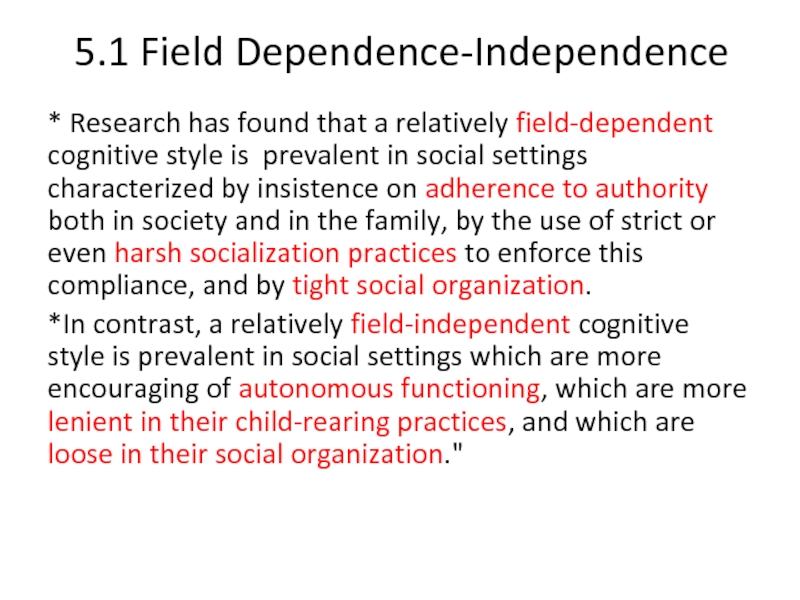

* Research has found that a relatively field-dependent cognitive

style is prevalent in social settings characterized by insistence on adherence to authority both in society and in the family, by the use of strict or even harsh socialization practices to enforce this compliance, and by tight social organization.

*In contrast, a relatively field-independent cognitive style is prevalent in social settings which are more encouraging of autonomous functioning, which are more lenient in their child-rearing practices, and which are loose in their social organization."

*In contrast, a relatively field-independent cognitive style is prevalent in social settings which are more encouraging of autonomous functioning, which are more lenient in their child-rearing practices, and which are loose in their social organization."

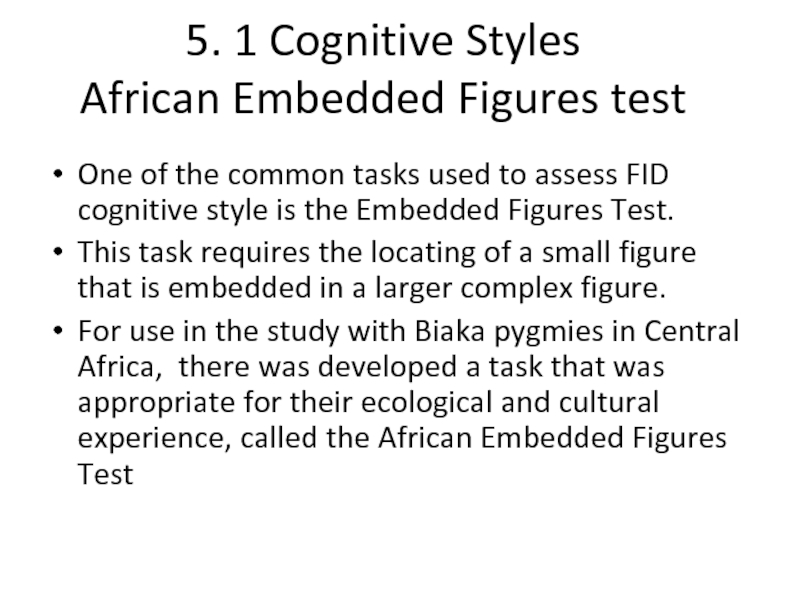

Слайд 315. 1 Cognitive Styles

African Embedded Figures test

One of the common tasks

used to assess FID cognitive style is the Embedded Figures Test.

This task requires the locating of a small figure that is embedded in a larger complex figure.

For use in the study with Biaka pygmies in Central Africa, there was developed a task that was appropriate for their ecological and cultural experience, called the African Embedded Figures Test

This task requires the locating of a small figure that is embedded in a larger complex figure.

For use in the study with Biaka pygmies in Central Africa, there was developed a task that was appropriate for their ecological and cultural experience, called the African Embedded Figures Test

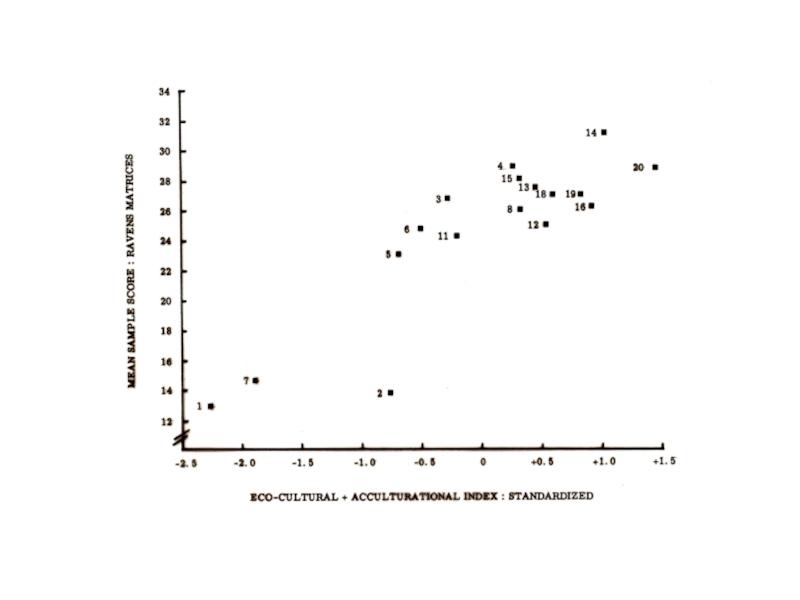

Слайд 335.1 Cognitive Styles

Although sometimes used as a measure of general intelligence,

Ravens Matrices have also been considered to be part of the FID cognitive style.

In research across a number of societies [ranging from hunting/gathering to agricultural], variations in performance has been found to be related to the ecocultural setting of the group.

In research across a number of societies [ranging from hunting/gathering to agricultural], variations in performance has been found to be related to the ecocultural setting of the group.

Слайд 355.2. East / West Cognitive Styles

Research on cognitive styles in

Eastern and Western cultures has been carried out by Nisbett

He began with observations about ancient Greece and China, arguing that they were “drastically different in ways that led to different economic, political and social arrangements” .

He noted that in China, “agricultural peoples need to get along with one another”, whereas in Greece, “hunting, herding, fishing and trade do not require living in the same stable community”.

He began with observations about ancient Greece and China, arguing that they were “drastically different in ways that led to different economic, political and social arrangements” .

He noted that in China, “agricultural peoples need to get along with one another”, whereas in Greece, “hunting, herding, fishing and trade do not require living in the same stable community”.

Слайд 365.2. East / West Cognitive Styles

He further argued that in agricultural

communities, “causality would be seen as located in the field or in the relation between object and the field” .

These observations were then linked to the cognitive style of field-dependence , and to the ecocultural basis of cognition

These observations were then linked to the cognitive style of field-dependence , and to the ecocultural basis of cognition

Слайд 375.2. East/ West Cognitive Styles

In this work, a distinction is made

between more holistic, and more analytic ways of thinking.

The former is seen as characteristic of East Asian populations, the latter of Westerners, especially Euro-Americans.

The basic proposition is that “… there are indeed dramatic differences in the nature of Asian and European thought processes”.

The former is seen as characteristic of East Asian populations, the latter of Westerners, especially Euro-Americans.

The basic proposition is that “… there are indeed dramatic differences in the nature of Asian and European thought processes”.

Слайд 385.2. East/ West Cognitive Styles

Nisbett denies that “everyone has the same

basic cognitive processes…or that all rely on the same tools for perception, memory, causal analysis, categorization and inference”

In a series of experiments, Nisbett and colleagues indeed found differences between Eastern and Western participants in performance on a variety of cognitive tasks.

In a series of experiments, Nisbett and colleagues indeed found differences between Eastern and Western participants in performance on a variety of cognitive tasks.

Слайд 395.2. East/ West Cognitive Styles

These tasks include:

the presentation of objects in

contexts, and asking participants to detect changes in the background or foreground.

requesting participants to say whether a thing is an object or a substance.

An important question regarding the claims of East-West cognition researchers is about the ‘depth’ of these cognitive performance differences.

Nisbett has noted that “Most of the time, in fact, Easterners and Westerners were found to behave in ways that were qualitatively distinct” [emphasis added] (Nisbett, 2003).

requesting participants to say whether a thing is an object or a substance.

An important question regarding the claims of East-West cognition researchers is about the ‘depth’ of these cognitive performance differences.

Nisbett has noted that “Most of the time, in fact, Easterners and Westerners were found to behave in ways that were qualitatively distinct” [emphasis added] (Nisbett, 2003).

Слайд 405.2. East/ West Cognitive Styles

The conclusion that there are qualitative differences

in basic processes, however, is not supported by their review of their own evidence.

For example:

-“Americans found it harder to detect changes in the background of scenes and Japanese found it harder to detect changes in objects in the foreground”, and

- When shown a thing, Japanese are twice as likely to regard it as a substance than as an object and Americans are twice as likely to regard it as an object than as a substance” [emphases added] (Nibett, 2003).

For example:

-“Americans found it harder to detect changes in the background of scenes and Japanese found it harder to detect changes in objects in the foreground”, and

- When shown a thing, Japanese are twice as likely to regard it as a substance than as an object and Americans are twice as likely to regard it as an object than as a substance” [emphases added] (Nibett, 2003).

Слайд 415.2. East/West Cognitive Styles

Two issues are important here:

- First, we

see no evidence of qualitative differences in performance: apparently all participants could perform these tasks, but to different degrees; hence there can be no claim of a cognitive process being present in one group but absent in the other.

Second, even if there were qualitative differences in performance, this would not permit an easy claim of there being differences in underlying basic cognitive processes. As noted earlier, the inferences required to go back from performance to process is a complex one, which these researchers seem not to examine.

Taken together, these comments support the view that cultures and individuals develop ways of perceiving and cognizing their environments that allow them to best adapt to the demands that they confront in their daily lives.

These are the hallmarks of the cognitive styles approach.

Second, even if there were qualitative differences in performance, this would not permit an easy claim of there being differences in underlying basic cognitive processes. As noted earlier, the inferences required to go back from performance to process is a complex one, which these researchers seem not to examine.

Taken together, these comments support the view that cultures and individuals develop ways of perceiving and cognizing their environments that allow them to best adapt to the demands that they confront in their daily lives.

These are the hallmarks of the cognitive styles approach.

Слайд 426. Conclusion

Perception and cognition are activities and processes of the organism

that are universal.

However, they are influenced by experience in, and knowledge acquired in particular ecologies and cultures.

Thus, cross-cultural differences should be expected, even predicted from a knowledge of these ecological and cultural influences.

However, they are influenced by experience in, and knowledge acquired in particular ecologies and cultures.

Thus, cross-cultural differences should be expected, even predicted from a knowledge of these ecological and cultural influences.