- Главная

- Разное

- Дизайн

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Аналитика

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Красота и здоровье

- Финансы

- Государство

- Путешествия

- Спорт

- Недвижимость

- Армия

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

The Germanic invasions of Britain презентация

Содержание

- 1. The Germanic invasions of Britain

- 2. The Germanic invasions of Britain The withdrawal

- 4. Our source for these early days of

- 5. According to this work — written in

- 6. Other tribes represented in these early invasions

- 7. The christianisation of England The English were

- 8. Distribution of the Germanic tribes The Germanic

- 9. Old English kingdoms In the beginning of

- 10. Dialects of Old English The dialects of

Слайд 2The Germanic invasions of Britain

The withdrawal of the Romans from England

in the early 5th century left a political vacuum. The Celts of the south were attacked by tribes from the north and in their desperation sought help from abroad. There are parallels for this at other points in the history of the British Isles. Thus in the case of Ireland, help was sought by Irish chieftains from their Anglo-Norman neighbours in Wales in the late 12th century in their internal squabbles. This heralded the invasion of Ireland by the English. Equally with the Celts of the 5th century the help which they imagined would solve their internal difficulties turned out to be a boomerang which turned on them.

Слайд 4Our source for these early days of English history is the Ecclesiastical History of the English People written

by a monk called the Venerable Bede around 730 in the monastery of Jarrow in Co. Durham (i.e. on the north east coast of England).

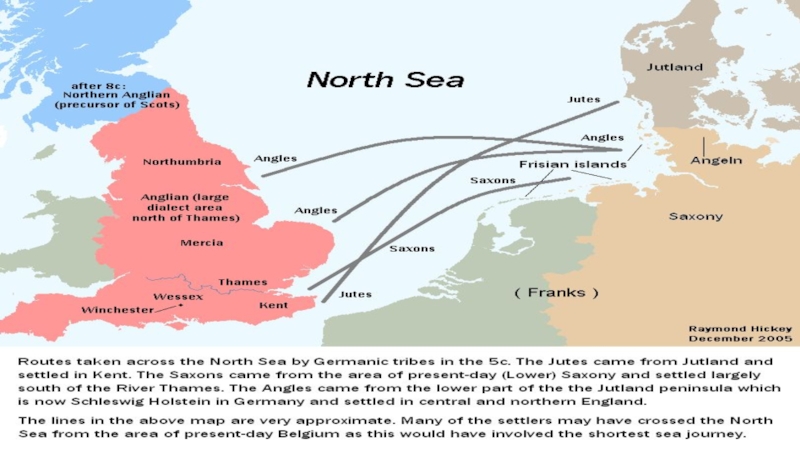

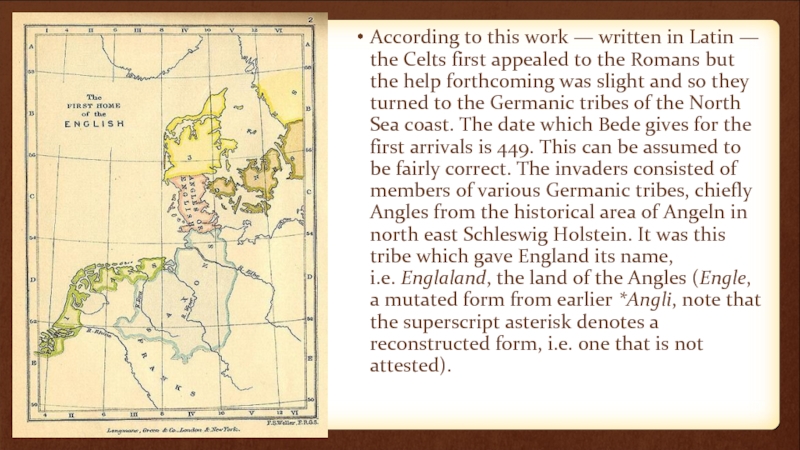

Слайд 5According to this work — written in Latin — the Celts

first appealed to the Romans but the help forthcoming was slight and so they turned to the Germanic tribes of the North Sea coast. The date which Bede gives for the first arrivals is 449. This can be assumed to be fairly correct. The invaders consisted of members of various Germanic tribes, chiefly Angles from the historical area of Angeln in north east Schleswig Holstein. It was this tribe which gave England its name, i.e. Englaland, the land of the Angles (Engle, a mutated form from earlier *Angli, note that the superscript asterisk denotes a reconstructed form, i.e. one that is not attested).

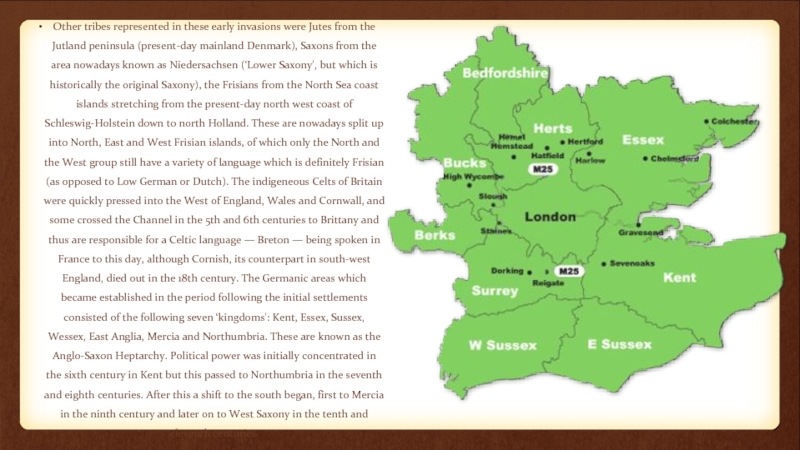

Слайд 6Other tribes represented in these early invasions were Jutes from the

Jutland peninsula (present-day mainland Denmark), Saxons from the area nowadays known as Niedersachsen (‘Lower Saxony’, but which is historically the original Saxony), the Frisians from the North Sea coast islands stretching from the present-day north west coast of Schleswig-Holstein down to north Holland. These are nowadays split up into North, East and West Frisian islands, of which only the North and the West group still have a variety of language which is definitely Frisian (as opposed to Low German or Dutch). The indigeneous Celts of Britain were quickly pressed into the West of England, Wales and Cornwall, and some crossed the Channel in the 5th and 6th centuries to Brittany and thus are responsible for a Celtic language — Breton — being spoken in France to this day, although Cornish, its counterpart in south-west England, died out in the 18th century. The Germanic areas which became established in the period following the initial settlements consisted of the following seven ‘kingdoms': Kent, Essex, Sussex, Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria. These are known as the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. Political power was initially concentrated in the sixth century in Kent but this passed to Northumbria in the seventh and eighth centuries. After this a shift to the south began, first to Mercia in the ninth century and later on to West Saxony in the tenth and eleventh centuries.

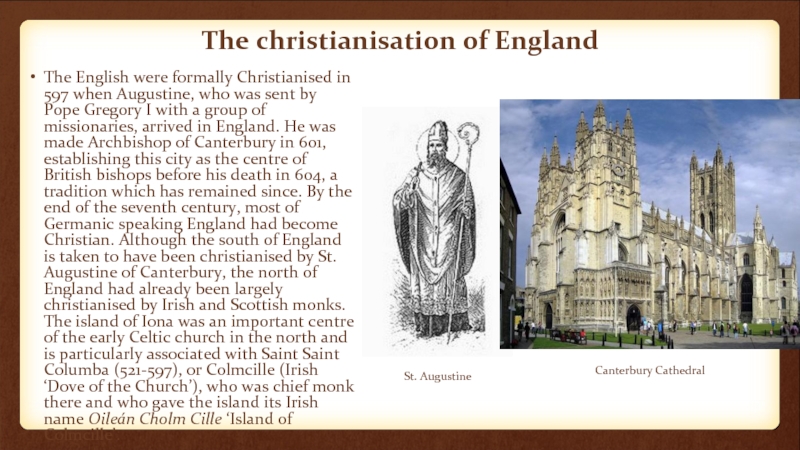

Слайд 7The christianisation of England

The English were formally Christianised in 597 when

Augustine, who was sent by Pope Gregory I with a group of missionaries, arrived in England. He was made Archbishop of Canterbury in 601, establishing this city as the centre of British bishops before his death in 604, a tradition which has remained since. By the end of the seventh century, most of Germanic speaking England had become Christian. Although the south of England is taken to have been christianised by St. Augustine of Canterbury, the north of England had already been largely christianised by Irish and Scottish monks. The island of Iona was an important centre of the early Celtic church in the north and is particularly associated with Saint Saint Columba (521-597), or Colmcille (Irish ‘Dove of the Church’), who was chief monk there and who gave the island its Irish name Oileán Cholm Cille ‘Island of Colmcille’.

St. Augustine

Canterbury Cathedral

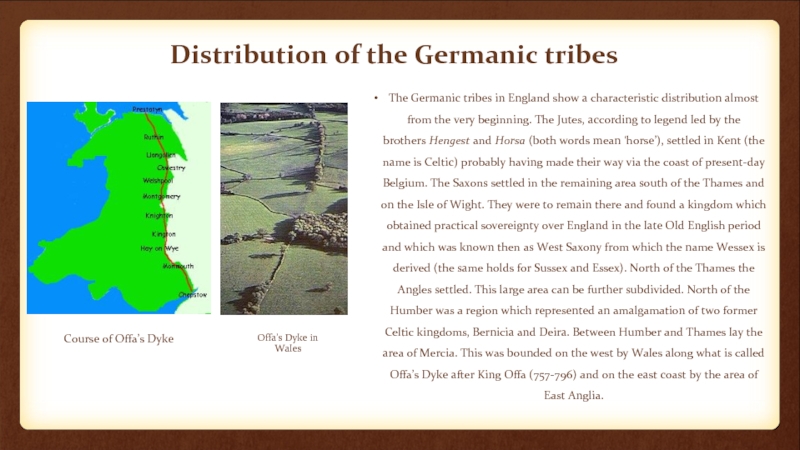

Слайд 8Distribution of the Germanic tribes

The Germanic tribes in England show a

characteristic distribution almost from the very beginning. The Jutes, according to legend led by the brothers Hengest and Horsa (both words mean ‘horse’), settled in Kent (the name is Celtic) probably having made their way via the coast of present-day Belgium. The Saxons settled in the remaining area south of the Thames and on the Isle of Wight. They were to remain there and found a kingdom which obtained practical sovereignty over England in the late Old English period and which was known then as West Saxony from which the name Wessex is derived (the same holds for Sussex and Essex). North of the Thames the Angles settled. This large area can be further subdivided. North of the Humber was a region which represented an amalgamation of two former Celtic kingdoms, Bernicia and Deira. Between Humber and Thames lay the area of Mercia. This was bounded on the west by Wales along what is called Offa’s Dyke after King Offa (757-796) and on the east coast by the area of East Anglia.

Course of Offa’s Dyke

Offa’s Dyke in Wales

Слайд 9Old English kingdoms

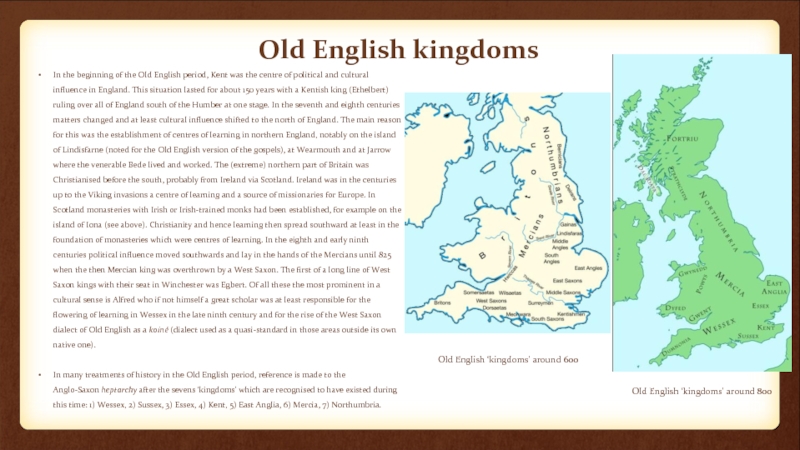

In the beginning of the Old English period, Kent

was the centre of political and cultural influence in England. This situation lasted for about 150 years with a Kentish king (Ethelbert) ruling over all of England south of the Humber at one stage. In the seventh and eighth centuries matters changed and at least cultural influence shifted to the north of England. The main reason for this was the establishment of centres of learning in northern England, notably on the island of Lindisfarne (noted for the Old English version of the gospels), at Wearmouth and at Jarrow where the venerable Bede lived and worked. The (extreme) northern part of Britain was Christianised before the south, probably from Ireland via Scotland. Ireland was in the centuries up to the Viking invasions a centre of learning and a source of missionaries for Europe. In Scotland monasteries with Irish or Irish-trained monks had been established, for example on the island of Iona (see above). Christianity and hence learning then spread southward at least in the foundation of monasteries which were centres of learning. In the eighth and early ninth centuries political influence moved southwards and lay in the hands of the Mercians until 825 when the then Mercian king was overthrown by a West Saxon. The first of a long line of West Saxon kings with their seat in Winchester was Egbert. Of all these the most prominent in a cultural sense is Alfred who if not himself a great scholar was at least responsible for the flowering of learning in Wessex in the late ninth century and for the rise of the West Saxon dialect of Old English as a koiné (dialect used as a quasi-standard in those areas outside its own native one).

In many treatments of history in the Old English period, reference is made to the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy after the sevens ‘kingdoms’ which are recognised to have existed during this time: 1) Wessex, 2) Sussex, 3) Essex, 4) Kent, 5) East Anglia, 6) Mercia, 7) Northumbria.

In many treatments of history in the Old English period, reference is made to the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy after the sevens ‘kingdoms’ which are recognised to have existed during this time: 1) Wessex, 2) Sussex, 3) Essex, 4) Kent, 5) East Anglia, 6) Mercia, 7) Northumbria.

Old English ‘kingdoms’ around 600

Old English ‘kingdoms’ around 800

Слайд 10Dialects of Old English

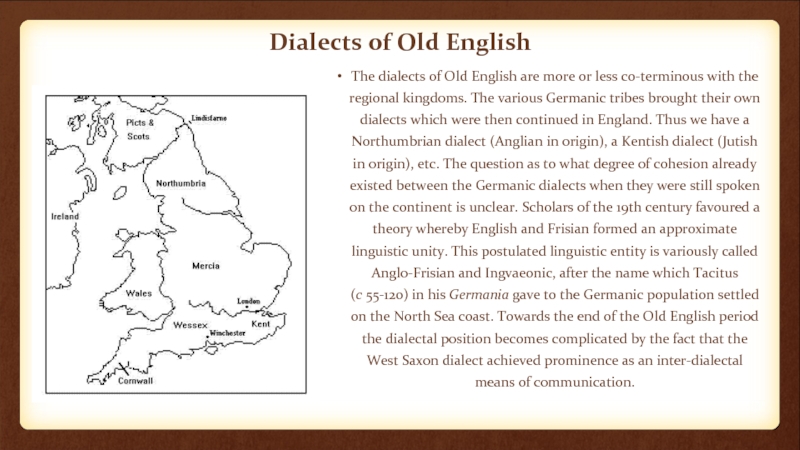

The dialects of Old English are more or

less co-terminous with the regional kingdoms. The various Germanic tribes brought their own dialects which were then continued in England. Thus we have a Northumbrian dialect (Anglian in origin), a Kentish dialect (Jutish in origin), etc. The question as to what degree of cohesion already existed between the Germanic dialects when they were still spoken on the continent is unclear. Scholars of the 19th century favoured a theory whereby English and Frisian formed an approximate linguistic unity. This postulated linguistic entity is variously called Anglo-Frisian and Ingvaeonic, after the name which Tacitus (c 55-120) in his Germania gave to the Germanic population settled on the North Sea coast. Towards the end of the Old English period the dialectal position becomes complicated by the fact that the West Saxon dialect achieved prominence as an inter-dialectal means of communication.