Papadatos- University of Geneva

- Главная

- Разное

- Дизайн

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Аналитика

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Красота и здоровье

- Финансы

- Государство

- Путешествия

- Спорт

- Недвижимость

- Армия

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

The comintern and the Western Communist Parties 1930-1949 презентация

Содержание

- 2. The comintern and the Western

- 3. КУТВ - КУНМЗ – МЛШ

- 4. The cadres of the foreign communist parties

- 5. In order to create an “inflexible activist

- 6. During the moment of "Bolshevisation", in the

- 7. KYTV – the iranian exemple

- 8. KUTV had received students from East and

- 9. On 21 January 1921, the Central Committee

- 10. General subjects such as

- 15. KUTV endured a difficult birth. 1921 was

- 16. In the summer of 1923, a large

- 17. Students also served as information channels between

- 18. The university founded a decade earlier with

- 19. He became chair of the Persian–Afghan

- 20. The contours of Soviet foreign policy had

- 21. In 1937, as the Stalinist purges were

- 24. International Lenin School Between 1926

- 25. In the Europe of the 1960s, the

- 26. In the year of the Lenin

- 27. Murphy himself, a former Sheffield engineer, was

- 28. In its first two objectives, the equipment

- 29. What was therefore most distinctive about the

- 30. Moreover, it is striking that in the

- 31. While thus reinforcing moral sanctions, political anathemas

- 32. In reality, recruitment to the school was

- 33. The CPGB’s proletarian credentials were second to

- 34. By the 1935 intake, there were complaints

- 35. These past and present associations were carefully

- 36. The democratic centralism practised by communist parties

- 37. The issue of party discipline raises particularly

- 38. In France, Waldeck Rochet succeeded Thorez as

- 39. The international lenin school and the

- 40. Between 1926 and 1938,

- 41. The comintern and the Western Communist Parties: 1930-1949

Слайд 3 КУТВ - КУНМЗ – МЛШ

Коммунисти́ческий университе́т трудя́щихся Восто́ка

Коммунистический университет

национальных меньшинств Запада имени Мархлевского

Международная ленинская школа

Alfred Kurella, one of the main leaders of the cultural policy of the Comintern said: "Marxism conceives the essence of humanity as the result of a process in which the concrete, sensual, individual and active elements are at the same time object and subject, creator and creature of oneself”.

Международная ленинская школа

Alfred Kurella, one of the main leaders of the cultural policy of the Comintern said: "Marxism conceives the essence of humanity as the result of a process in which the concrete, sensual, individual and active elements are at the same time object and subject, creator and creature of oneself”.

Слайд 4The cadres of the foreign communist parties are educated in Moscow.

When they return to their country of origin, on the one hand, they enjoy the authority of the International. For this, they must not only to be trained specifically but also be supervised and controlled by the “policy of the cadres".

For this purpose, the Soviet party develops a network of schools after the Russian Civil War, where the communists follow the program, either in group, either through a program of self-education, supported by an instructor. This orientation is repeated and modified by Stalinism. To fuel the collective effort of productivity, an immense appeal to learn (and from 1935 to "cultivate") is launched by the Soviet government in order to engage the soviet citizens. Meanwhile, the cadres are gradually controlled by special educational institutions, some of which are open to foreign communists.

For this purpose, the Soviet party develops a network of schools after the Russian Civil War, where the communists follow the program, either in group, either through a program of self-education, supported by an instructor. This orientation is repeated and modified by Stalinism. To fuel the collective effort of productivity, an immense appeal to learn (and from 1935 to "cultivate") is launched by the Soviet government in order to engage the soviet citizens. Meanwhile, the cadres are gradually controlled by special educational institutions, some of which are open to foreign communists.

Слайд 5In order to create an “inflexible activist army” of cadres “on

behalf of the proletarian cause”, a specific model of training is proposed and introduced by the Soviet government. The above international schools are implementing a pedagogical educational program aiming to analyze the purpose as much as the techniques. But, despite the goal of universalism of the Communist International, the reality of Soviet party is constantly reflecting a different modus operandi.

The"purification" (чистки) of a "case" - delo - from the 1930s, the "verification" (проверки) and the exchange of information between the Party’s executives is also one of the available tools during the educational process. The Communists of the 1930 must transform themselves into "true Bolsheviks“. In order to achieve this goal, they have to know how to improve themselves. Such a transformation requires the implementation of introspective techniques.

The"purification" (чистки) of a "case" - delo - from the 1930s, the "verification" (проверки) and the exchange of information between the Party’s executives is also one of the available tools during the educational process. The Communists of the 1930 must transform themselves into "true Bolsheviks“. In order to achieve this goal, they have to know how to improve themselves. Such a transformation requires the implementation of introspective techniques.

Слайд 6During the moment of "Bolshevisation", in the midst of 1920s, the

international schools' rules where established but this framework was finally institutionalized when the Stalinization of the Comintern took place (1928).

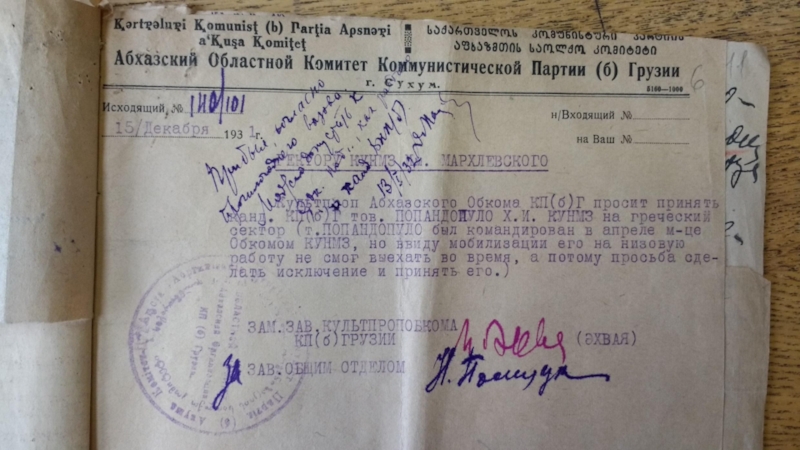

Foreign communists are distributed according to linguistic criteria. There are many sectors: French, German, Italian, English, Greek etc. Each school is structured according to a hierarchical and complex organization : we have an interaction between the instances of the school officials and those of the party and the union.

So we find at various levels and in each sector, responsible administrators but also student representatives. There is, moreover, a party committee made up of management representatives, administration, the teaching profession and the students, political office, as well as a representative of the party (partorg) and a union representative (proforg), appointed by their peers.

Foreign communists are distributed according to linguistic criteria. There are many sectors: French, German, Italian, English, Greek etc. Each school is structured according to a hierarchical and complex organization : we have an interaction between the instances of the school officials and those of the party and the union.

So we find at various levels and in each sector, responsible administrators but also student representatives. There is, moreover, a party committee made up of management representatives, administration, the teaching profession and the students, political office, as well as a representative of the party (partorg) and a union representative (proforg), appointed by their peers.

Слайд 7 KYTV – the iranian exemple

The Communist University for Laborers of

the East, abbreviated KUTV in Russian, opened in Moscow in 1921—a time of heady enthusiasm in the young Soviet state, when revolution in the East seemed a natural and imminent sequel to the October Revolution. KUTV was the first communist educational institution set up specifically for students from the Orient, and by the second half of the 1920s it had developed into one of the most important centers of Soviet Orientalism. This experimental “smithy of cadres” not only trained eager sympathizers to become teachers and revolutionaries in their native lands, but also sought to bring about a paradigm shift in the study of the East by emphasizing contemporary social and economic history through a Marxist lens and by redistributing the tools of Orientalist scholarship to Orientals themselves.

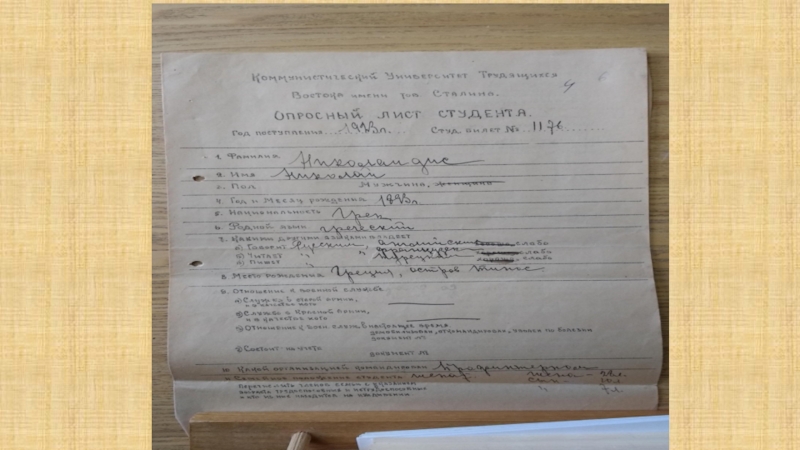

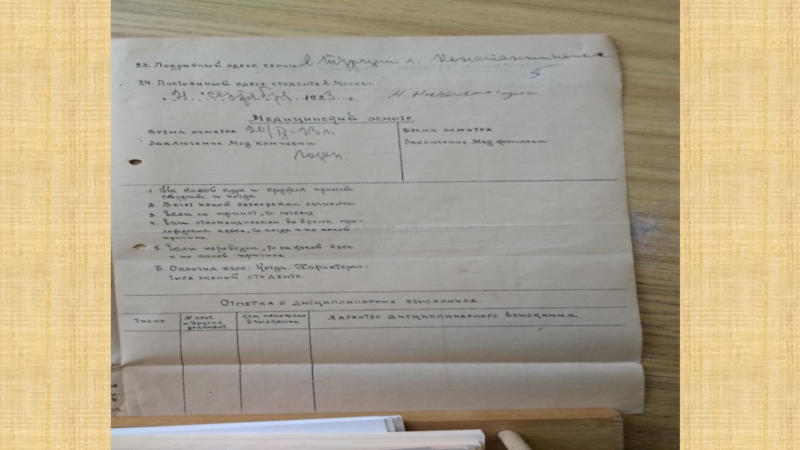

Слайд 8KUTV had received students from East and Southeast Asia. Many KUTV

alumni became important communist leaders and functionaries: some, such as Hồ Chí Minh and Liu Shaoqi, even rising to lead their countries. Although such brilliant successes were not to be for communists in Iran, the Iranian presence at KUTV was strong among both students and teachers, some of whom returned to Iran to spread learning and revolution; while others, such as Ladbon Esfandiari, Abdol-Hossein Hesabi, Abolqasem Zarreh and Avetis Sultanzadeh, remained in the Soviet Union as scholars of Iran, influencing the development of Soviet Orientalism through their teaching and writing, and often serving simultaneously in the Soviet political apparatus.

Слайд 9On 21 January 1921, the Central Committee of the Russian Communist

Party resolved to organize what it called “Eastern Courses” under the aegis of the Peoples’ Commissariat for Ethnic Affairs. These were soon given the name KUTV, and already on 21 April of that year, another resolution established KUTV as a separate university, open to students from the traditional Orient regardless of nationality.

KUTV was a hybrid educational institution, not merely a Sverdlovka for non- Russian speakers but also a realization of the Soviet vision of Oriental studies as a discipline engaging the eastern present through an unashamedly politicized framework that looked beyond the traditional focus on literary and architectural monuments of the past. Yet even within the context of Soviet Orientalism, KUTV was conceived to be different from other Soviet Orientalist institutions, such as the Institute of Studies in Moscow, the Orientalist Department of the Military Academy of the Red Army, and the institutes in Petrograd in that it was to train Orientals, and not only to become teachers and researchers but also to work in their home countries as propagandists and revolutionaries.

KUTV was a hybrid educational institution, not merely a Sverdlovka for non- Russian speakers but also a realization of the Soviet vision of Oriental studies as a discipline engaging the eastern present through an unashamedly politicized framework that looked beyond the traditional focus on literary and architectural monuments of the past. Yet even within the context of Soviet Orientalism, KUTV was conceived to be different from other Soviet Orientalist institutions, such as the Institute of Studies in Moscow, the Orientalist Department of the Military Academy of the Red Army, and the institutes in Petrograd in that it was to train Orientals, and not only to become teachers and researchers but also to work in their home countries as propagandists and revolutionaries.

Слайд 10

General subjects such as mathematics, physics, chemistry, world history and geography

were taught, but the core curriculum consisted of political economy, historical materialism and the history of the Russian Bolshevik Communist Party. It was mandatory to study the history of the East—of each student’s home country, in particular —and “The Colonial and Ethnic Question.” Early syllabi included the contemporary history of Turkey, Iran and Afghanistan, with more countries added in later years.

Слайд 15KUTV endured a difficult birth. 1921 was a year of extreme

hardship and hunger in the Soviet Union. Students arriving from distant, warm climates had to adapt to Moscow winters and ruinous post-revolution and post-civil war living conditions. The “university” itself was very much a work in progress when these first students arrived, with the curriculum still undetermined and practically no teaching materials to help overcome the formidable language gap: not even Russian language grammars, much less Marxist literature in eastern languages. It was often hard even to find pencils and notebooks, so pupils were provided with large sheets of paper that had to be cut and sewn into notebooks.

Слайд 16In the summer of 1923, a large group of students and

graduates of the pedagogical program were sent to various regions to organize new departments. The Baku branch served Iranians, Azeris and Turks in the region; the branch in Irkutsk was for students from the Far East, offering classes in Korean; in Sterlitamak, for Bashkirians; in Petrozavodsk, for Karelians; and in Krasnokokshaisk, for Maris. The largest branch was founded in Tashkent: it could accommodate 140 Kyrgyz, Turkmen, Uzbek and other students, with a separate school for another 140 female students and several provincial schools throughout the region.

The students combined the study of Marx with Mohammedism or Buddhism. It was not easy to reform this multiethnic, multilingual mass into a unified communist family, nor was it easy for the students themselves to overcome the traditions that were a part of their daily existence (in other words, to renounce them). At times, weapons needed to be confiscated—daggers and Nagants (revolvers). This could be met with desperate resistance on the students’ part. It was explained during lectures that in our country only the Red Army and the militia have the right to possess weapons and that the students’ prime weapon would be Marxism–Leninism, which must be studied in order to graduate from KUTV fully armed with Marxism.

The students combined the study of Marx with Mohammedism or Buddhism. It was not easy to reform this multiethnic, multilingual mass into a unified communist family, nor was it easy for the students themselves to overcome the traditions that were a part of their daily existence (in other words, to renounce them). At times, weapons needed to be confiscated—daggers and Nagants (revolvers). This could be met with desperate resistance on the students’ part. It was explained during lectures that in our country only the Red Army and the militia have the right to possess weapons and that the students’ prime weapon would be Marxism–Leninism, which must be studied in order to graduate from KUTV fully armed with Marxism.

Слайд 17Students also served as information channels between the research and political

apparatus in the Soviet capital and the distant East considered so crucial to the communist project. The Iranian students were especially active: they elected their own “Communist Bureau” that maintained contact with the Iranian Communist Party, receiving regular updates about life in Iran and the progress of revolutionary movements. The bureau held general student gatherings for information exchanges about life in the students’ home countries. In addition to translating Soviet materials into Persian for the Iranian press, students likewise translated summaries of Iranian newspapers into Russian.

Every year, the KUTV student body included several young Iranian women. At the end of the first year, three out of the twenty-one Iranian students were women. From 1925 to 1928, two female Iranian students taught Persian in addition to their studies.

Every year, the KUTV student body included several young Iranian women. At the end of the first year, three out of the twenty-one Iranian students were women. From 1925 to 1928, two female Iranian students taught Persian in addition to their studies.

Слайд 18The university founded a decade earlier with hardly a pencil or

a notebook had expanded into a respected, well-equipped think tank of which the original KUTV was only a part. By the mid-1920s, its library had amassed almost 50,000 books and publications. In the 1930s, “textbook brigades” worked in offices dedicated to producing educational materials. The students arriving to study at KUTV in the 1930s were very different from the barely literate provincials of the early 1920s. Communist parties in eastern countries were sending their most prominent figures, Central Committee members or leading revolutionaries. The level of scholarship had developed immensely, thanks to the hard-fought creation of reference materials and statistical data on the contemporary East.

Abulqasim Zarreh, the young Tehrani intellectual who in the early 1920s, as one of KUTV’s first students, had edited the broadsheets hanging on the university walls, rose to the top of the academic ladder at KUTV and other Moscow Orientalist institutions. By 1931, he was chief editor of all translations of Marxist–Leninist literature published by KUTV.

Abulqasim Zarreh, the young Tehrani intellectual who in the early 1920s, as one of KUTV’s first students, had edited the broadsheets hanging on the university walls, rose to the top of the academic ladder at KUTV and other Moscow Orientalist institutions. By 1931, he was chief editor of all translations of Marxist–Leninist literature published by KUTV.

Слайд 19

He became chair of the Persian–Afghan Department at KUTV in 1932

and chair of the Persian–Afghan–Arab Department at the Moscow Institute for Oriental Studies in 1934. Zarreh combined academic with political and government activities, working in the cryptographic department of the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) as a linguist and expert on Iran.

But while the university was thriving, the revolution in the East was stalling, not least in Iran, where Reza Shah had consolidated power. The Bulgarian revolutionary Georgi Dimitrov, who studied at KUTV in the 1930s, commented on how the growing reaction to and oppression of communists abroad—including Reza Shah’s crackdowns—was affecting the university: “We are continually losing the most valuable parts of our team in the struggle. After all, we are not a society of scholars, but a fighting movement that’s always in the direct line of fire. Our most energetic, bravest and self-aware individuals are always leading the charge. And it is these whom the Enemy hunts first—the vanguard, who are killed and thrown into prisons or labor camps, where they are tortured”.

But while the university was thriving, the revolution in the East was stalling, not least in Iran, where Reza Shah had consolidated power. The Bulgarian revolutionary Georgi Dimitrov, who studied at KUTV in the 1930s, commented on how the growing reaction to and oppression of communists abroad—including Reza Shah’s crackdowns—was affecting the university: “We are continually losing the most valuable parts of our team in the struggle. After all, we are not a society of scholars, but a fighting movement that’s always in the direct line of fire. Our most energetic, bravest and self-aware individuals are always leading the charge. And it is these whom the Enemy hunts first—the vanguard, who are killed and thrown into prisons or labor camps, where they are tortured”.

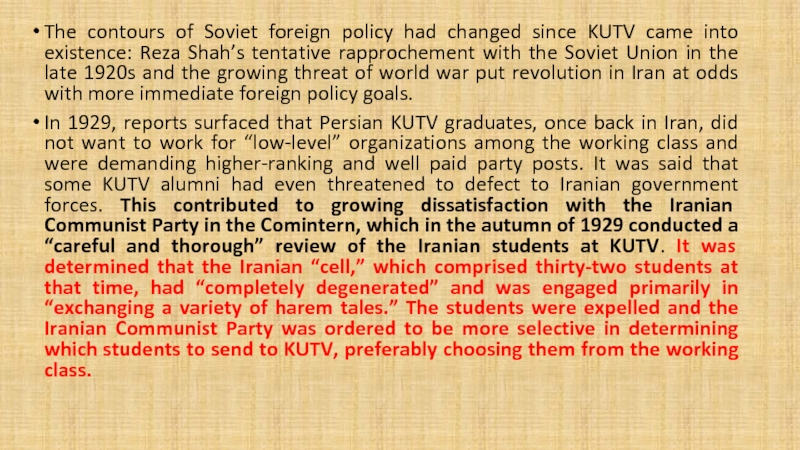

Слайд 20The contours of Soviet foreign policy had changed since KUTV came

into existence: Reza Shah’s tentative rapprochement with the Soviet Union in the late 1920s and the growing threat of world war put revolution in Iran at odds with more immediate foreign policy goals.

In 1929, reports surfaced that Persian KUTV graduates, once back in Iran, did not want to work for “low-level” organizations among the working class and were demanding higher-ranking and well paid party posts. It was said that some KUTV alumni had even threatened to defect to Iranian government forces. This contributed to growing dissatisfaction with the Iranian Communist Party in the Comintern, which in the autumn of 1929 conducted a “careful and thorough” review of the Iranian students at KUTV. It was determined that the Iranian “cell,” which comprised thirty-two students at that time, had “completely degenerated” and was engaged primarily in “exchanging a variety of harem tales.” The students were expelled and the Iranian Communist Party was ordered to be more selective in determining which students to send to KUTV, preferably choosing them from the working class.

In 1929, reports surfaced that Persian KUTV graduates, once back in Iran, did not want to work for “low-level” organizations among the working class and were demanding higher-ranking and well paid party posts. It was said that some KUTV alumni had even threatened to defect to Iranian government forces. This contributed to growing dissatisfaction with the Iranian Communist Party in the Comintern, which in the autumn of 1929 conducted a “careful and thorough” review of the Iranian students at KUTV. It was determined that the Iranian “cell,” which comprised thirty-two students at that time, had “completely degenerated” and was engaged primarily in “exchanging a variety of harem tales.” The students were expelled and the Iranian Communist Party was ordered to be more selective in determining which students to send to KUTV, preferably choosing them from the working class.

Слайд 21In 1937, as the Stalinist purges were sweeping across the USSR,

a bureaucratic restructuring occurred that signaled the beginning of the end for KUTV. The university was divided into two independent organizations: one retained the name KUTV, but now only students with Soviet citizenship remained; the foreign students were transferred from KUTV to the Academic Research Institute of Ethnic and Colonial Problems (NII NKP), a new incarnation of the NIA NKP.

In January and February of 1938, the purges reached the Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies. Many of the Institute’s scholars also taught at KUTV, and after the arrests of Zarreh, Sultanzadeh and others, the university, now deprived of the majority of its faculty, was obliged to shut down. Officially, the closure was attributed to the ongoing restructuring of the educational system for future party functionaries. At the same time, the party Central Committee and the Comintern closed down the NII NKP as well.

In January and February of 1938, the purges reached the Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies. Many of the Institute’s scholars also taught at KUTV, and after the arrests of Zarreh, Sultanzadeh and others, the university, now deprived of the majority of its faculty, was obliged to shut down. Officially, the closure was attributed to the ongoing restructuring of the educational system for future party functionaries. At the same time, the party Central Committee and the Comintern closed down the NII NKP as well.

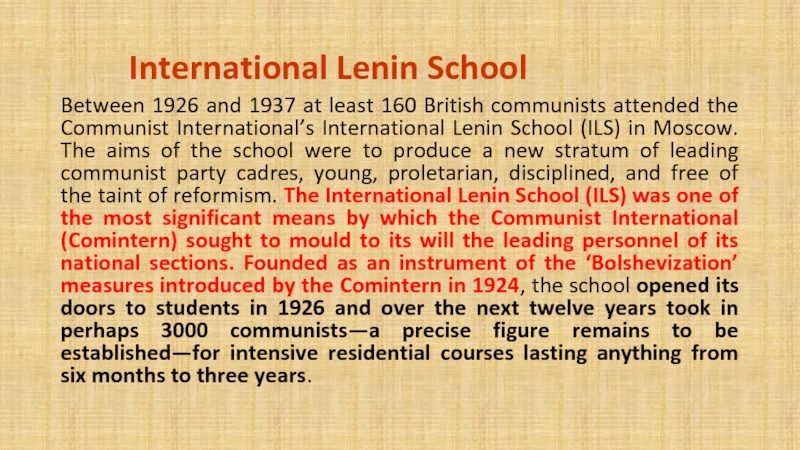

Слайд 24 International Lenin School

Between 1926 and 1937 at least 160

British communists attended the Communist International’s International Lenin School (ILS) in Moscow. The aims of the school were to produce a new stratum of leading communist party cadres, young, proletarian, disciplined, and free of the taint of reformism. The International Lenin School (ILS) was one of the most significant means by which the Communist International (Comintern) sought to mould to its will the leading personnel of its national sections. Founded as an instrument of the ‘Bolshevization’ measures introduced by the Comintern in 1924, the school opened its doors to students in 1926 and over the next twelve years took in perhaps 3000 communists—a precise figure remains to be established—for intensive residential courses lasting anything from six months to three years.

Слайд 25In the Europe of the 1960s, the school’s graduates included three

de facto heads of government, namely Yugoslavia’s Marshal Tito, Poland’s Wladyslaw Gomulka, and the GDR’s Erich Honecker, and leaders of significant oppositional parties in the west, such as the French Communist Party (PCF) general secretary Waldeck Rochet. Moreover, the school established a model of party education which for much of the communist world proved at least as enduring.

ILS students went on to achieve prominence as national or district trade union officials, including the Scottish and Welsh miners’ leaders Alec Moffat and Will Paynter, the journalists’ president Allen Hutt, and a number of district officials of the Amalgamated Engineering Union. Nevertheless, it is not for its wider impact on British society that the school deserves our attention, but as perhaps the most extreme of the Comintern’s intrusions into the history of the British left by the fashioning in Moscow of a trained, responsive, and carefully vetted cohort of revolutionary activists.

ILS students went on to achieve prominence as national or district trade union officials, including the Scottish and Welsh miners’ leaders Alec Moffat and Will Paynter, the journalists’ president Allen Hutt, and a number of district officials of the Amalgamated Engineering Union. Nevertheless, it is not for its wider impact on British society that the school deserves our attention, but as perhaps the most extreme of the Comintern’s intrusions into the history of the British left by the fashioning in Moscow of a trained, responsive, and carefully vetted cohort of revolutionary activists.

Слайд 26

In the year of the Lenin School’s inception, a leading British

communist, Tom Bell, warned that ‘we must have patience and not jump into schemes that suggest we can turn out Leninists like sausages from a machine’. Ten years later, having been appointed director of the school’s ‘E-sector’ for English-language students, Bell stated frankly: ‘With regard to the students, we have not had very good results’. To assess how far, and in what respects, this was indeed the case, we first need to consider the stated objectives against which the school’s results can most plausibly be measured.

Слайд 27Murphy himself, a former Sheffield engineer, was an impressive example of

the alternative potentialities of working-class autodidacticism and the Labour college tradition. ‘For the first time in human history’, J. T. Murphy announced shortly after the school opened, ‘the International working-class will have a real revo- lutionary university capable of training revolutionary workers for real Communist leadership’.

Briefly summarized, the objectives Murphy set out were the formation of a revolutionary elite; its induction into the theories of Marxism–Leninism; its stiffening with the vigilance, discipline, and commitment of the Bolsheviks; and the effecting by these means of a decisive break with the rotten social-democratic traditions from which communism was still breaking clear.

Briefly summarized, the objectives Murphy set out were the formation of a revolutionary elite; its induction into the theories of Marxism–Leninism; its stiffening with the vigilance, discipline, and commitment of the Bolsheviks; and the effecting by these means of a decisive break with the rotten social-democratic traditions from which communism was still breaking clear.

Слайд 28In its first two objectives, the equipment with a special body

of knowledge of a party elite, the school followed closely in the steps of its unacknowledged prototype, the central party school of the German SPD. Such institutions, described by Robert Michels as exemplifying the oligarchical tendencies of party organization, may be contrasted with the more inclusive and egalitarian traditions of the Labour college movement, or even the CPGB’s initial ‘Party School’ system with its requirements that every party member pass through a basic course and examination.

Taught at a speed which many found exacting, students at the ILS were given courses in working-class history, the political economy of imperialism, Marxist theory, and the experience of proletarian dictatorship, the latter consolidated by practical work in a Soviet economic enterprise and probationary membership of the CPSU.

Taught at a speed which many found exacting, students at the ILS were given courses in working-class history, the political economy of imperialism, Marxist theory, and the experience of proletarian dictatorship, the latter consolidated by practical work in a Soviet economic enterprise and probationary membership of the CPSU.

Слайд 29What was therefore most distinctive about the ILS was the inculcation

of discipline both as the highest party virtue and as an indispensable condition of attendance at the school itself. On arrival, they were then kept in a special ‘isolation block’ and only allowed into the school’s general living quarters once they had been approved by its ‘man- date commission’. Breaches of conspiracy were treated with considerable gravity. For indiscretion in divulging the purpose of one’s visit or sending letters home by other than the school’s official channels, one would be reported to the Comintern cadres commission and censured for any violations of secrecy. Jock Kane, one of a Scottish communist miners’ clan, was thus brought to book for having fourteen party associates and relatives learn of his affairs.

The British students and the British party as a whole were regarded somewhat as dilettantes in such matters, and in 1931 the party’s own Moscow representative commented resignedly that ‘the conspirative nature of the school’ seemed ‘in some sections of our Party ... to be almost forgotten’.

The British students and the British party as a whole were regarded somewhat as dilettantes in such matters, and in 1931 the party’s own Moscow representative commented resignedly that ‘the conspirative nature of the school’ seemed ‘in some sections of our Party ... to be almost forgotten’.

Слайд 30Moreover, it is striking that in the school’s later enrolments there

are far more students for whom we have no further details of party activities, and it seems likely that the school was now being used far more actively as a direct source of recruitment into clandestine activities. Some students, we know, were recruited to the ultra-secretive OMS school, the OMS being responsible for the Comintern’s illegal communications.

William Duncan, previously a London employee at the Moscow Narodny bank had been instructed to give up open political work and was described as one of the channels through which the British communists received their Comintern subsidies. The best known and most sensational cases are those of the convicted spies, Percy Glading and Douglas Springhall, arrested in 1938 and 1943, respectively. However, in both cases several years had passed since they had attended the school and it is not at all clear that the ILS provided their introduction to clandestine work.

William Duncan, previously a London employee at the Moscow Narodny bank had been instructed to give up open political work and was described as one of the channels through which the British communists received their Comintern subsidies. The best known and most sensational cases are those of the convicted spies, Percy Glading and Douglas Springhall, arrested in 1938 and 1943, respectively. However, in both cases several years had passed since they had attended the school and it is not at all clear that the ILS provided their introduction to clandestine work.

Слайд 31While thus reinforcing moral sanctions, political anathemas had their own more

fundamental significance as the school’s basic raison d’être. Politically, the aim was to effect a final break with reformism, lingering as an influence on the founding generation of communist activists, and the ideal Lenin student was one uncontaminated by such a past. Alfred Kurella, the German communist then overseeing the French party schools, specifically counterposed this new ‘Leninist generation’ of party activists with those carrying within them the residues of social democracy or syndicalism.

This basic purpose helps situate the Lenin School within the constantly changing perspectives of communist politics. In one sense, it may be, and usually is, described as an instrument for the Stalinization of the Comintern. Recruitment criteria for the Lenin School were stringent, precise, and theoretically mandatory. Among other provisions, the students were required to be of working-class or peasant origin, in perfect health, aged no more than 35, members of the party or Young Communist League for at least a year, and proven in some form of class struggle.

This basic purpose helps situate the Lenin School within the constantly changing perspectives of communist politics. In one sense, it may be, and usually is, described as an instrument for the Stalinization of the Comintern. Recruitment criteria for the Lenin School were stringent, precise, and theoretically mandatory. Among other provisions, the students were required to be of working-class or peasant origin, in perfect health, aged no more than 35, members of the party or Young Communist League for at least a year, and proven in some form of class struggle.

Слайд 32In reality, recruitment to the school was a matter of continuous

and unavoidable tension, if only because it was impossible to meet its demands for significant numbers of the most promising activists while at the same time assuaging the Comintern’s no less insistent appetite for immediate political results at home. Inevitably, complaints are therefore recorded of multifarious personal deficiencies precisely the inverse of the Comintern’s own utterly unreal expectations.

In 1931, at the height of the school’s recruitment, it identified seven particular varieties of undesirable, including those with no political experience, no grounding in mass work, no capacity for scientific study, insufficient length of party membership, concealed past allegiances ‘alien to the communist movement’, and poor or desperate health, ‘whom the school is obliged to cure rather than teach’. The document does not refer specifically to the CPGB, and it is clear that all communist parties must have transgressed these rules to some extent.

In 1931, at the height of the school’s recruitment, it identified seven particular varieties of undesirable, including those with no political experience, no grounding in mass work, no capacity for scientific study, insufficient length of party membership, concealed past allegiances ‘alien to the communist movement’, and poor or desperate health, ‘whom the school is obliged to cure rather than teach’. The document does not refer specifically to the CPGB, and it is clear that all communist parties must have transgressed these rules to some extent.

Слайд 33The CPGB’s proletarian credentials were second to none, and, according to

its own figures, British ILS students over the period 1929–34 included 91 per cent workers, with 68 per cent working in basic industry. Though no occupational breakdown was provided, our own figures suggest that coal mining and engineering provided by far the largest contingents, with around one-quarter and one-fifth of the students, respectively, while significant groups were also drawn from among textile workers and railway men.

By 1930, with the spread of industrial unrest to the textile areas, there was a perceptible increase in recruitment from Lancashire, though the West Riding by contrast seems to have provided more of a reception area for returning students. Given that students tended to be nominated by the districts, the role of the district organizer was also a significant factor. For example, the emergence of the weak party district of Birmingham as a significant line of supply in the 1930s may have reflected the influence of sympathetic functionaries like Maurice Ferguson and Tom Roberts, both themselves products of the school.

By 1930, with the spread of industrial unrest to the textile areas, there was a perceptible increase in recruitment from Lancashire, though the West Riding by contrast seems to have provided more of a reception area for returning students. Given that students tended to be nominated by the districts, the role of the district organizer was also a significant factor. For example, the emergence of the weak party district of Birmingham as a significant line of supply in the 1930s may have reflected the influence of sympathetic functionaries like Maurice Ferguson and Tom Roberts, both themselves products of the school.

Слайд 34By the 1935 intake, there were complaints that ‘basic industries’ were

largely unrepresented, and that most of the students were ‘clerks and office workers’. Also, the school set specific quotas for women students—in 1932, for example, at least one-fifth of the forty student places—and overall the CPGB seems to have met these requirements. Of the 148 students whose sex we can be certain of, thirty, or just over one-fifth were women, a figure comparing favourably with their proportion of the party membership as a whole.

Almost at the school’s outset, J. T. Murphy contrasted the school’s directors, ‘accustomed to the discipline of the Russian Communist Party’, with a student body revealing all the ‘immaturities’ of their sponsoring parties, ‘the ghosts of the Social-Democratic past, the Social-Democratic associations with the present, the syndicalist associations etc’.

Almost at the school’s outset, J. T. Murphy contrasted the school’s directors, ‘accustomed to the discipline of the Russian Communist Party’, with a student body revealing all the ‘immaturities’ of their sponsoring parties, ‘the ghosts of the Social-Democratic past, the Social-Democratic associations with the present, the syndicalist associations etc’.

Слайд 35These past and present associations were carefully noted on the students’

entry into the school, while on their departure it was not uncommon for evaluations to refer dismissively to those ‘remnants of petty bourgeois and labour aristocracy’ which, if not connoting drunkenness and oversleeping, were taken to refer to malign and resistant strains of reformism.

Increasingly, it was hoped that a new generation would emerge untouched by such legacies. Waldeck Rochet, a student in 1930–1, is described by his biographer as a ‘model’ ILS cadre, untramelled by a reformist past and adhering directly to the PCF, and in France is said to have typified a so-called ‘Thorez generation’ of communist leaders. In Britain, too, a similar cohort may be identified, born, like Thorez and Waldeck Rochet, in the earliest years of the century, and typically having had their most formative political experiences in the Young Communist League (YCL).

Increasingly, it was hoped that a new generation would emerge untouched by such legacies. Waldeck Rochet, a student in 1930–1, is described by his biographer as a ‘model’ ILS cadre, untramelled by a reformist past and adhering directly to the PCF, and in France is said to have typified a so-called ‘Thorez generation’ of communist leaders. In Britain, too, a similar cohort may be identified, born, like Thorez and Waldeck Rochet, in the earliest years of the century, and typically having had their most formative political experiences in the Young Communist League (YCL).

Слайд 36The democratic centralism practised by communist parties seems almost like a

codification of this iron law, reinforced in this case by the students’ physical removal from the base of the party and manifested in the interdependence of training and advancement in a seamless cadres policy. It is therefore hardly surprising that Lenin School students should have secured immediate and dramatic advances to Communist Party leadership positions, as happened elsewhere.

Of 102 graduates between 1929 and 1934, only six were regarded as having worked unsatisfactorily, while in the decade from 1929 around one-eighth of returning students spent some time on the party’s central committee, providing twenty of its ninety-five members over that period. There was nothing accidental about this process. Having already brought on ‘new proletarian elements’ in 1929, the 1932 central committee was consciously intended as a departure from its predecessors ‘in social composition, the election of new elements who had not previously been members of reformist parties, the introduction into the CC of a whole series of comrades who had received political training at the ILS etc’.

Of 102 graduates between 1929 and 1934, only six were regarded as having worked unsatisfactorily, while in the decade from 1929 around one-eighth of returning students spent some time on the party’s central committee, providing twenty of its ninety-five members over that period. There was nothing accidental about this process. Having already brought on ‘new proletarian elements’ in 1929, the 1932 central committee was consciously intended as a departure from its predecessors ‘in social composition, the election of new elements who had not previously been members of reformist parties, the introduction into the CC of a whole series of comrades who had received political training at the ILS etc’.

Слайд 37The issue of party discipline raises particularly complex issues, not just

because of students’ susceptibility to other influences, either prior or subsequent to attendance at the school, but because the school itself provided both a general culture of and an intense induction into the current party line. The result occasionally was a certain rigidity when it came to fundamental changes in the Comintern line.

For many European communist parties, the Lenin School’s legacy was a lasting one. In Finland, until the 1960s at least half of the party’s leading members had attended the school: in 1963, for example, nine of thirteen Political Bureau members had attended the school, with another having attended the Moscow party school in the 1950s.

For many European communist parties, the Lenin School’s legacy was a lasting one. In Finland, until the 1960s at least half of the party’s leading members had attended the school: in 1963, for example, nine of thirteen Political Bureau members had attended the school, with another having attended the Moscow party school in the 1950s.

Слайд 38In France, Waldeck Rochet succeeded Thorez as the communists’ general secretary

in 1964. In both countries a simulacrum of the Lenin School model was maintained for decades afterwards. In Finland it was named the Sirola Institute after the leader of the ILS’s Finnish sector. In France, residential courses of one to six months also provided a ‘total school experience’ for the vast majority of national and federal cadres. From both countries some hundreds of students continued the trip to Moscow for residential courses, lasting anything from four months to two years. Perhaps these did not always make that much difference to one’s prospects within the party, but in France they provided a Moscow-trained general secretary in the shape of Georges Marchais until as late as 1993.

Слайд 39

The international lenin school and the communist party of Great Britain

Situated in Moscow, and shrouded in secrecy, the International Lenin School (ILS) was founded in 1926 as an instrument for the “Bolshevization” of the Comintern and its national sections. Roughly summarized from what may be the only authorized public description of the school, the ILS’ aims were the formation of a revolutionary elite; the induction of this elite into the disciplines of Marxism-Leninism; its indoctrination with the vigilance, discipline, and commitment of the Bolsheviks; and the making of a decisive break with any lingering social-democratic traditions within the communist movement. This last goal also involved the removal of an older leadership cohort tainted by “petty bourgeois” influences and its replacement with trained Leninist cadres drawn from the core sections of the working class.

Conclusion

Слайд 40

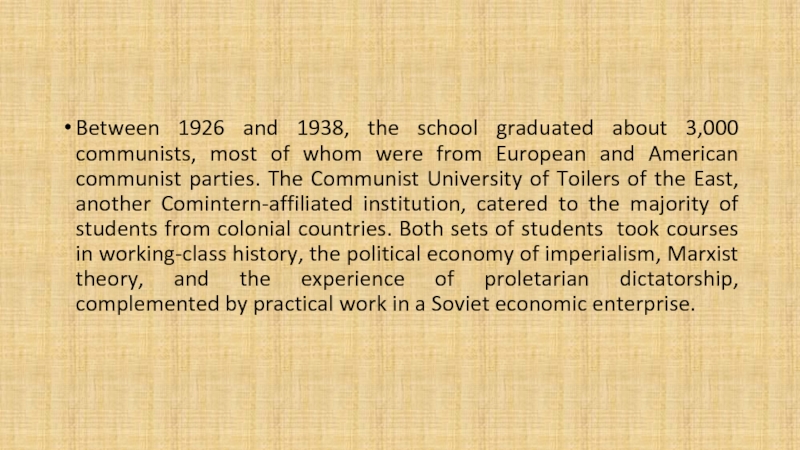

Between 1926 and 1938, the school graduated about 3,000 communists, most

of whom were from European and American communist parties. The Communist University of Toilers of the East, another Comintern-affiliated institution, catered to the majority of students from colonial countries. Both sets of students took courses in working-class history, the political economy of imperialism, Marxist theory, and the experience of proletarian dictatorship, complemented by practical work in a Soviet economic enterprise.