- Главная

- Разное

- Дизайн

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Аналитика

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Красота и здоровье

- Финансы

- Государство

- Путешествия

- Спорт

- Недвижимость

- Армия

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Post-soviet sphere. Dialogues and conflicts презентация

Содержание

- 1. Post-soviet sphere. Dialogues and conflicts

- 2. RUSSIAN EMPIRE

- 3. KIEVAN RUS The population included a considerable

- 4. An inner circle of Finnish-speaking tribes to

- 5. MUSCOVITE STATE. Ethnic groups that engaged in

- 6. 3. Some where between these two types

- 7. BASIC PATTERNS OF AN EXPANSIONIST POLICY An

- 8. THE GATHERING OF THE LANDS OF THE

- 9. Muscovite policy initially pursued the aggressive aims.

- 10. Policy: simultaneously of the traditions of steppe

- 11. THE CONQUEST AND PENETRATION OF SIBERIA. The

- 12. POLICY TOWARDS SIBERIA. The majority of the

- 13. THE BASHKIRS. The Bashkirs were Turkic-speaking Muslims,

- 14. THE NOGAI TATARS. The Turkic-speaking and Islamic

- 15. THE KALMYKS. The Kalmyks were western Mongolian

- 16. THE CRIMEAN TATARS. In the first half

- 17. From the time of Peter the Great

- 18. THE COSSACKS. The Cossacks had settled along

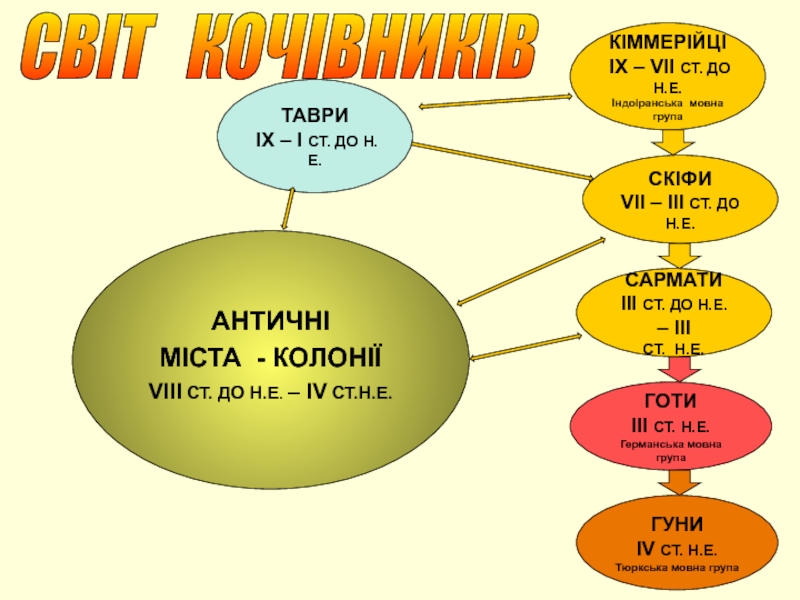

Слайд 3KIEVAN RUS

The population included a considerable proportion of tribes who spoke

Finnish and Baltic languages, a small number of Turkic-speaking soldiers, and in early period, Scandinavian Varangians.

A vast empire on the city state of Novgorod and inhabited by numerous non-slavs ethic groups arose between the 11 and 14 centuries in the north-western part of the area settled by eastern Slavs.

A vast empire on the city state of Novgorod and inhabited by numerous non-slavs ethic groups arose between the 11 and 14 centuries in the north-western part of the area settled by eastern Slavs.

Слайд 4An inner circle of Finnish-speaking tribes to the north – Karelians,

Vots, Izhora and Veps – was ruled directly from Novgorod, and an outer circle was subject to loose tributary rule. They included the Finnish-speaking Lapps in the North and further to the north-east, the Zyrians and Permiaks, who were also the Finnish-speaking, the Ugric-speaking Ostiaks and Voguls, and the Samoyeds.

In the principalities of the north-east and in the Grand Duchy of Muscovy Russians lived side by side with Finnish-speaking ethnic groups/ The majority of the aboriginal inhabitants (Merya, Muroma and Ves) were assimilated in linguistic and religious terms . Only the western Mordvinians retained the status of an independent ethnic groups.

In the principalities of the north-east and in the Grand Duchy of Muscovy Russians lived side by side with Finnish-speaking ethnic groups/ The majority of the aboriginal inhabitants (Merya, Muroma and Ves) were assimilated in linguistic and religious terms . Only the western Mordvinians retained the status of an independent ethnic groups.

Слайд 5MUSCOVITE STATE.

Ethnic groups that engaged in agriculture and forestry, which were

integrated in administrative, economic and social terms, which had accepted the Orthodox faith (Karelians, Veps, Izhora, Zyrians and Permiaks). They have been russified to a great extent.

The hunters, fishermen of the northern and north-eastern periphery. They were subject to a loose tributary rule that left their inner socio-political structure and animist religion untouched (Samoyeds, Lapps, Ostiaks and Voguls).

The hunters, fishermen of the northern and north-eastern periphery. They were subject to a loose tributary rule that left their inner socio-political structure and animist religion untouched (Samoyeds, Lapps, Ostiaks and Voguls).

Слайд 63. Some where between these two types were Mordvinians, Cheremis, Votiaks,

Besermians on the borders of the Khanate of Kazan. They engaged primarily in agriculture and forestry, and their areas had to some extent been integrated in administrative and economic termes, and had already been reached by Russian settlers. However, they retained a non-Russian elite and their animists value system.

4. The forth type consisted of foreigners (Tatars, Greeks, Italians). They were active in the fields of administration, diplomacy, or worked in technical professions.

4. The forth type consisted of foreigners (Tatars, Greeks, Italians). They were active in the fields of administration, diplomacy, or worked in technical professions.

Слайд 7BASIC PATTERNS OF AN EXPANSIONIST POLICY

An astute kind of diplomacy –

the technique of divide et impera

Support of foreign elites

Stepwise strategy that led from protectorates whose status was sealed by a declaration of loyalty to complete annexation at a later date

The acquisition by purchase of smaller territories

Military conquest and brutal repression

The legitimation of annexations with political arguments

Support of foreign elites

Stepwise strategy that led from protectorates whose status was sealed by a declaration of loyalty to complete annexation at a later date

The acquisition by purchase of smaller territories

Military conquest and brutal repression

The legitimation of annexations with political arguments

Слайд 8THE GATHERING OF THE LANDS OF THE GOLDEN HORDE

The conquest of

the Khanate Kazan (1552), Astrakhan (1556)

Muscovite policy towards Kazan remained within the framework of traditional steppe politics. By using military and economic pressure (for example trade boycott) and well-tried method of attracting the support of the Tatar elite, Moscow sought to reinstall a khan who was well-disposed towards it and thereby to secure the allegiance of Kazan (1532,1546,1551).

The decisive steps leading up to annexation were first taken in 1551, when the fortress of Sviiazhsk was constructed on the territory of the Khanate, and when the part of the Khanate which lay on the right bank of the Volga was incorporated into the Muscovite State.

It was only in the spring 1552, after the final attempt to install a puppet khan had failed, that the decision was taken to conquer Kazan.

In 1556 Muscovy then proceeded to annex the Khanate of Astrakhan.

Muscovite policy towards Kazan remained within the framework of traditional steppe politics. By using military and economic pressure (for example trade boycott) and well-tried method of attracting the support of the Tatar elite, Moscow sought to reinstall a khan who was well-disposed towards it and thereby to secure the allegiance of Kazan (1532,1546,1551).

The decisive steps leading up to annexation were first taken in 1551, when the fortress of Sviiazhsk was constructed on the territory of the Khanate, and when the part of the Khanate which lay on the right bank of the Volga was incorporated into the Muscovite State.

It was only in the spring 1552, after the final attempt to install a puppet khan had failed, that the decision was taken to conquer Kazan.

In 1556 Muscovy then proceeded to annex the Khanate of Astrakhan.

Слайд 9Muscovite policy initially pursued the aggressive aims. The campaign against Kazan

took the form of crusade against Islam.

The male population of the town Kazan was put to death, mosques were razed to the ground. The khan and other Tatars of noble birth were deported to the interior of the Muscovite state and baptized. If they refused, they were put to death.

Tatars and non-Tatars rose up against the foreign rule.

The male population of the town Kazan was put to death, mosques were razed to the ground. The khan and other Tatars of noble birth were deported to the interior of the Muscovite state and baptized. If they refused, they were put to death.

Tatars and non-Tatars rose up against the foreign rule.

Слайд 10Policy: simultaneously of the traditions of steppe politics and of the

Novgorod and Muscovite policy towards non-Slav ethic groups.

Revolts were consistently put down with military force.

At the same time Muscovy established a system of fortress in order to control the areas concerned and to defend them against possible attacks from without.

The direct incorporation of the khanate into the Muscovite system of local government districts (uezd) can to some extent be explained by security concerns, and the Russian voevods who were in command of this administrative units also had military functions. But up to a point the khanate as a whole retained a special status, and was governed from a separate central department (Prikaz Kazanskogo Dvortsa).

The Muscovite policy of incorporation was also governed by economic considerations. The city of Kazan was taken over by Russians, and Russian merchants were ordered to settle in it. The towns of the Khanate became Russian enclaves in non-Russian environment. The land that had belonged to the khan or to aristocrats was given to Russian noblemen.

The pragmatic policy approach was based on cooperation with loyal non-Russian elites . They saved traditional privileges. The Tatar and Muslim elite was cooped into Russian nobility

Revolts were consistently put down with military force.

At the same time Muscovy established a system of fortress in order to control the areas concerned and to defend them against possible attacks from without.

The direct incorporation of the khanate into the Muscovite system of local government districts (uezd) can to some extent be explained by security concerns, and the Russian voevods who were in command of this administrative units also had military functions. But up to a point the khanate as a whole retained a special status, and was governed from a separate central department (Prikaz Kazanskogo Dvortsa).

The Muscovite policy of incorporation was also governed by economic considerations. The city of Kazan was taken over by Russians, and Russian merchants were ordered to settle in it. The towns of the Khanate became Russian enclaves in non-Russian environment. The land that had belonged to the khan or to aristocrats was given to Russian noblemen.

The pragmatic policy approach was based on cooperation with loyal non-Russian elites . They saved traditional privileges. The Tatar and Muslim elite was cooped into Russian nobility

Слайд 11THE CONQUEST AND PENETRATION OF SIBERIA.

The ethnic groups that inhabited Siberia

in 16-17 centuries divided into northern (the nomadic hunters and fishermen Tungus, Iukagir, Samoyeds, Tungus, Chukchi, Koriaks)) and southern (Buriats, Teleuts).None of the Siberian ethnic groups had any political organisation.

The initiative for Russian expansion to Siberia didn’t at first come from the state, but from the Stroganov family. These entrepreneurs had built up a semi-autonomous economic area in the north of Russia that was largely devoted to trade in salt and furs. In 158-1582 a troop of Cossaks in their pay conquered the capital of the Siberian Khanate. After some hesitation Muscovy followed and secured the Khanate with numerous fortresses (1586 Tiumen, 1587 Tobolsk, 1604 Tomsk).

The initiative for Russian expansion to Siberia didn’t at first come from the state, but from the Stroganov family. These entrepreneurs had built up a semi-autonomous economic area in the north of Russia that was largely devoted to trade in salt and furs. In 158-1582 a troop of Cossaks in their pay conquered the capital of the Siberian Khanate. After some hesitation Muscovy followed and secured the Khanate with numerous fortresses (1586 Tiumen, 1587 Tobolsk, 1604 Tomsk).

Слайд 12POLICY TOWARDS SIBERIA.

The majority of the Siberian ethnic groups put up

resistance to the Russians. The repeated outbursts of resistance strengthened the resolve of the Muscovite Government to pursue a policy of incorporation.

As a rule Muscovy confirmed the clan and tribal chieftains in their possessions and privileges, and conferred on them simple judicial duties and the task of local government. This mainly concerned the collection of iasak, which was usually paid with furs.

The representatives of the native elite were not co-opted into the nobility of the empire.

The regional administration did not obey their instractions. Corruption, illegal enslavement, robbery and acts of violence were a daily occurrence.

Russian expansion in Siberia has occasionally been compared to American expansion to the West. The brutal treatment of the native ethnic groups, whose traditional order was destroyed with the armed force, alcohol and disease have long been forgotten.

As a rule Muscovy confirmed the clan and tribal chieftains in their possessions and privileges, and conferred on them simple judicial duties and the task of local government. This mainly concerned the collection of iasak, which was usually paid with furs.

The representatives of the native elite were not co-opted into the nobility of the empire.

The regional administration did not obey their instractions. Corruption, illegal enslavement, robbery and acts of violence were a daily occurrence.

Russian expansion in Siberia has occasionally been compared to American expansion to the West. The brutal treatment of the native ethnic groups, whose traditional order was destroyed with the armed force, alcohol and disease have long been forgotten.

Слайд 13THE BASHKIRS.

The Bashkirs were Turkic-speaking Muslims, lived between the Kama and

Iaik, in the southern Urals. They were semi-nomadic and nomadic herdsmen. They were organized in clans and tribes.

After the conquest of Kazan certain groups of Bashkirs accepted Muscovite suzerainty. The fortress of Ufa had been established in 1586. A number of tribal chieftains entered the service of Muscovy and paid iasak to the tsar.

From the second half of the 17 century the state gradually began to levy taxes and demand services from the Bashkirs in a systematic manner.

After the rebellions of the 18 century the area was subsequently incorporated into the Russian empire in administrative terms. The section of the Bashkir elite had their rights and privileges confirmed and entered into the service of the Russian army in the form of cavalry units.

The lower classes continued to pay iasak.

After the conquest of Kazan certain groups of Bashkirs accepted Muscovite suzerainty. The fortress of Ufa had been established in 1586. A number of tribal chieftains entered the service of Muscovy and paid iasak to the tsar.

From the second half of the 17 century the state gradually began to levy taxes and demand services from the Bashkirs in a systematic manner.

After the rebellions of the 18 century the area was subsequently incorporated into the Russian empire in administrative terms. The section of the Bashkir elite had their rights and privileges confirmed and entered into the service of the Russian army in the form of cavalry units.

The lower classes continued to pay iasak.

Слайд 14THE NOGAI TATARS.

The Turkic-speaking and Islamic Nogai tatars lived between the

Volga and the sea of Aral. They were typical nomad horsemen, and were loosely organized into clans and tribes which sometimes united to form one or more hordes. The Small Horde placed itself under the protection of the Khan of Crimea. In the east one of the Hordes joined the Kazakhs, whereas the Great Horde in the centre was shaken by power struggles between the various clans.

After the conquest of the Volga khanates the Nogai Tatars of the Great Horde had become direct neighbours of Muscovy and more and more dependent on it in economic terms. Muscovy played the warring clans off against each other, and in 1557 Prince Ismail swore an oath to the tsar that was interpreted as a sign of subservience in Moscow.

Nogai Tatars served as mercenaries in the Russian Army, and certain aristocrats entered the service of the tsar.

After the conquest of the Volga khanates the Nogai Tatars of the Great Horde had become direct neighbours of Muscovy and more and more dependent on it in economic terms. Muscovy played the warring clans off against each other, and in 1557 Prince Ismail swore an oath to the tsar that was interpreted as a sign of subservience in Moscow.

Nogai Tatars served as mercenaries in the Russian Army, and certain aristocrats entered the service of the tsar.

Слайд 15THE KALMYKS.

The Kalmyks were western Mongolian tribes lived in the steppes

to the north of the Caspian Sea. They were nomardic herdsmen, and disciplined and feared warriors. They were organized in family clans and in hordes or tribes. On the Volga they united to form a khanate. The Kalmyks were lamaists.

Muscovi reached an agreement with the khan of the Kalmyks included with an oath of loyalty in 1655. For Muscovy this meant that that Kalmyks had become subjects of the tsar. For the Kalmyks it was simply a voluntary military alliance in the context of the politics of the steppe.

Muscovy needed these doughty warriors as a buffer in the south. The Khanate of the Kalmyks remained independent.

The nomadic Kalmyks were not integrated into Russian society, and retained their traditional internal socio-political order even in the 19 century, although their autonomy was gradually curtailed and their grazing lands reduced in size.

Muscovi reached an agreement with the khan of the Kalmyks included with an oath of loyalty in 1655. For Muscovy this meant that that Kalmyks had become subjects of the tsar. For the Kalmyks it was simply a voluntary military alliance in the context of the politics of the steppe.

Muscovy needed these doughty warriors as a buffer in the south. The Khanate of the Kalmyks remained independent.

The nomadic Kalmyks were not integrated into Russian society, and retained their traditional internal socio-political order even in the 19 century, although their autonomy was gradually curtailed and their grazing lands reduced in size.

Слайд 16THE CRIMEAN TATARS.

In the first half of the 16 century only

the khanate of the Crimean Tatars had not come under Russian rule by the 18 century.

The Turkic-speaking and Islamic Crimean Tatars were in a position to control the wide steppes to the north of the Black Sea? Not only on account of their outstanding military and organizational abilities, but also because of the support given them by the Ottoman Empire.

In the 18 century, the Khanate of Crimea was already well past its heyday. Its economy was in crisis, its social and political stability had been undermined by internal conflicts, and it became more and more dependent on the Sultan. Russia’s attitude to the Crimean Tatars was increasingly determined by its relations with the Ottoman Empire.

The Turkic-speaking and Islamic Crimean Tatars were in a position to control the wide steppes to the north of the Black Sea? Not only on account of their outstanding military and organizational abilities, but also because of the support given them by the Ottoman Empire.

In the 18 century, the Khanate of Crimea was already well past its heyday. Its economy was in crisis, its social and political stability had been undermined by internal conflicts, and it became more and more dependent on the Sultan. Russia’s attitude to the Crimean Tatars was increasingly determined by its relations with the Ottoman Empire.

Слайд 17From the time of Peter the Great onwards Russia attemped to

acquire access to the Black Sea.

1736-1739 – Russian troops defeated the Crimean Tatars and for a short time even ventured on to the Crimea itself.

1768-1774 – the result of Russia – Turkish war – the Ottoman Empire was dislodged from the northern shore of the Black Sea. The Khanate of the Crimean Tatars now stood alone against the might of the Russian empire.

The annexation of the Crimea occurred in three stages. The Crimea was conquered in 1771, and in the following year the Ottoman Protectorate over the Khanate of Crimea was replaced by a Russian one, although this guaranteed the existence of the Khanate as a free territory dependent on no one.

Four years later Russia appointed a new khan who implemented a series of reforms.

When the Tatar aristocracy rebelled against this, Catherine II ordered Russian troops to invade the territory. The last khan was deposed in 1783.

The methods which were used to incorporate the Khanate of Crimea initially resembled those that had been employed in the case of the Khanate of Kazan. The administrative structure of the Khanate was taken over and placed under the control of a Russian governor. The Russian authorities now worked together with the Tatar elite, whose landed property and privileges they guaranteed. The Muslim Tatars elite was co-opted into the nobility. The Tatars peasants also retained their land and their status as free state peasants.

This pragmatic policy was a success.

1736-1739 – Russian troops defeated the Crimean Tatars and for a short time even ventured on to the Crimea itself.

1768-1774 – the result of Russia – Turkish war – the Ottoman Empire was dislodged from the northern shore of the Black Sea. The Khanate of the Crimean Tatars now stood alone against the might of the Russian empire.

The annexation of the Crimea occurred in three stages. The Crimea was conquered in 1771, and in the following year the Ottoman Protectorate over the Khanate of Crimea was replaced by a Russian one, although this guaranteed the existence of the Khanate as a free territory dependent on no one.

Four years later Russia appointed a new khan who implemented a series of reforms.

When the Tatar aristocracy rebelled against this, Catherine II ordered Russian troops to invade the territory. The last khan was deposed in 1783.

The methods which were used to incorporate the Khanate of Crimea initially resembled those that had been employed in the case of the Khanate of Kazan. The administrative structure of the Khanate was taken over and placed under the control of a Russian governor. The Russian authorities now worked together with the Tatar elite, whose landed property and privileges they guaranteed. The Muslim Tatars elite was co-opted into the nobility. The Tatars peasants also retained their land and their status as free state peasants.

This pragmatic policy was a success.

Слайд 18THE COSSACKS.

The Cossacks had settled along the Don, the Volga, the

Iaik and the Terek since the 16 century. They were primarily Russian and Ukrainian peasants who had fled to escape from increased taxation and the extension of selfdom to the steppe frontier. They lived in fortified camps and worked as fishermen, hunters and herdsmen.

Russia used Cossacks in its conflicts with the nomads of the steppe, employing them as frontier guards.

The Cossacks developed a socio-political order that was totally different from that of the Russian autocracy. The most important decisions were taken by the circle (assembly). It also elected the ataman or leader.

The Russian government made use of eastern Slav Cossacks and peasants in order to open up and settle the wide expanses of the Steppe. The Ukranian steppe frontier was reorganized and called Novorossia.

Russia used Cossacks in its conflicts with the nomads of the steppe, employing them as frontier guards.

The Cossacks developed a socio-political order that was totally different from that of the Russian autocracy. The most important decisions were taken by the circle (assembly). It also elected the ataman or leader.

The Russian government made use of eastern Slav Cossacks and peasants in order to open up and settle the wide expanses of the Steppe. The Ukranian steppe frontier was reorganized and called Novorossia.